Children have lost control of their digital footprint by their fifth birthday simply by going to school.

The State of Data 2020 report

- is a call to action from teachers, parents and young people for change in law, policy and practice on data and digital rights in state education and its supporting infrastructure;

- maps the scope of every statutory data collection for the first time, from the Early Years to A-levels in attainment tests and the censuses collected by the Department for Education;

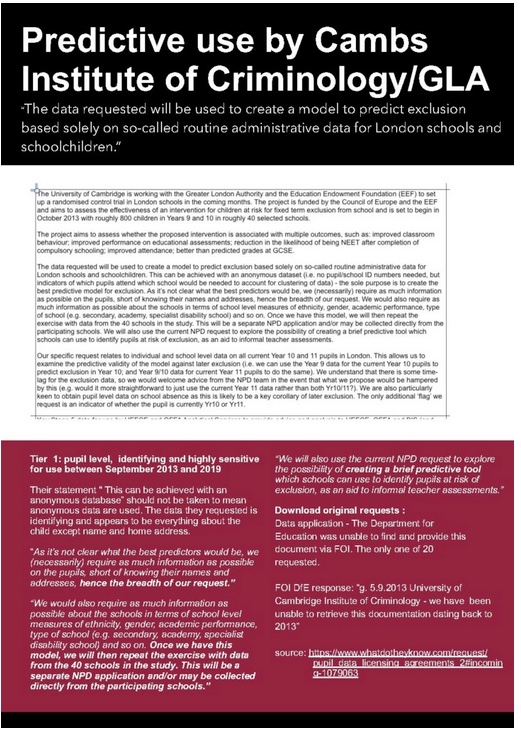

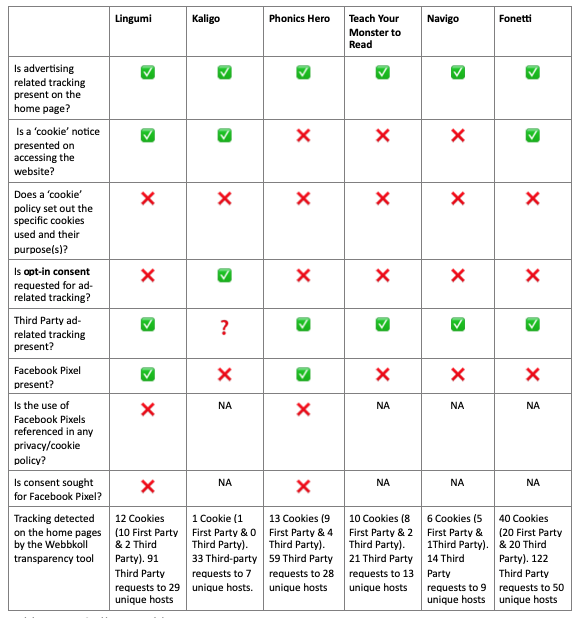

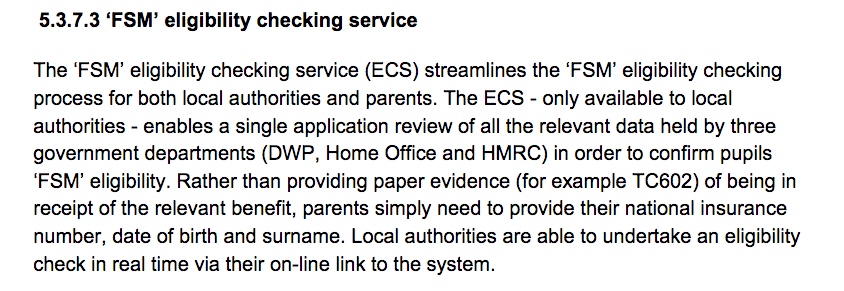

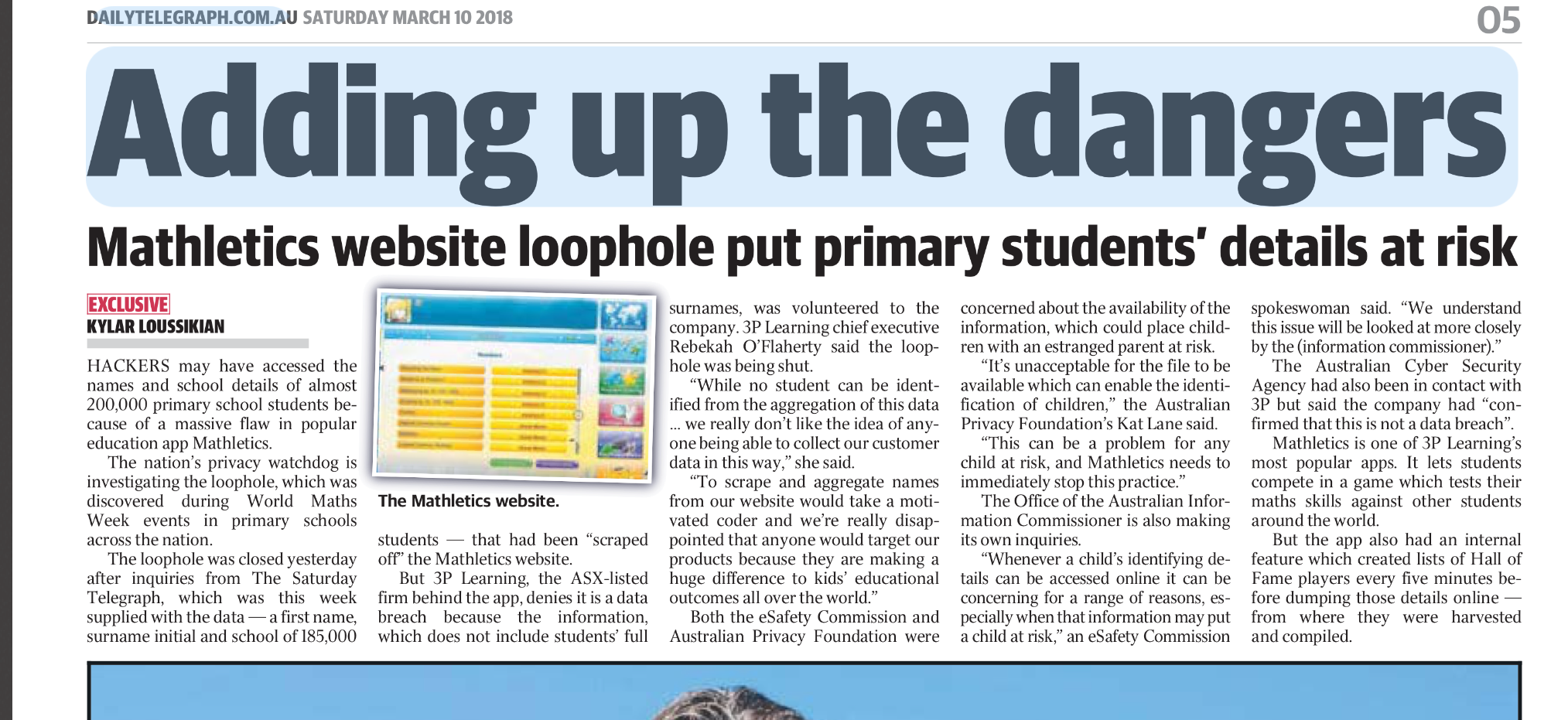

- reveals gaps in oversight, transparency and accountability in product trials and edTech that collect children's data; in what, why, and how it is used, through a selection of case studies.

Data protection law alone is inadequate to protect children’s rights and freedoms across the state education sector in England. Research trials are carried out routinely in classrooms without explicit parental consent and no opt-out of the intervention. Products marketed for pupils are increasingly invasive.[1] Students are forced to use remote invigilation tools that treat everyone as suspicious, with automated operations that fail to account for human differences, or that harm human dignity.[2]

This report asks government, policy and decision makers to recognise the harms that poor practice has on young people’s lives and to take action to build the needed infrastructure to realise the vision of a rights’ respecting environment in the digital landscape of state education in England.

We make recommendations on ten topics

- Legislation and statutory duties

- Assessment, Attainment, Accountability and Profiling

- Administrative data collections and national datasets

- Principles and practice using technology today

- EdTech evidence, efficacy, and export intentions

- Children’s rights in a digital environment

- Local data processing

- Higher Education

- Research

- Enforcement

Now is a critical moment for national decision makers if they are serious about the aims of the National Data Strategy[3] to empower individuals to control how their data is used. After the damning 2020 ICO audit[4] of national pupil data handling at the Department for Education, will you make the changes needed to build better: safe, trustworthy public datasets with the mechanisms that enable children and families to realise their rights or will you stick with more of the same; data breaches,[5] boycotts[6] and bust opportunity?

Will you act to safeguard the infrastructure and delivery of state education and our future sovereign ability to afford, control, and shape it, or drive the UK state to ever more dependence on Silicon Valley and Chinese edTech, proprietary infrastructure on which the delivery of education relies today.

The 2020 exam awarding process demonstrated the potential for discrimination in data, across historical datasets and in algorithmic decision making. While some may consider the middle of a global pandemic is not the best time to restructure school assessment, progress and accountability measures, change is inevitable since some collections were canceled under COVID-19. Now is the time to pause and get it right. We are also at a decisive moment for many schools to decide if, or which new technology to invest in, now that most of the COVID-19 free-trial offers are over.

Privacy isn’t only a tool to protect children’s lives, their human dignity and their future selves. The controls on companies’ access to children's data, is what controls the knowledge companies get about the UK delivery of education and the state education sector. That business intelligence is produced today by the public sector teachers and children who spend time administering and working in the digital systems. So while many companies offer their systems for free or at low cost to schools, schools have intangible costs in staff workload and support time, and donate those labour costs to companies for free. Our children are creating a resource that for-profit companies gain from.

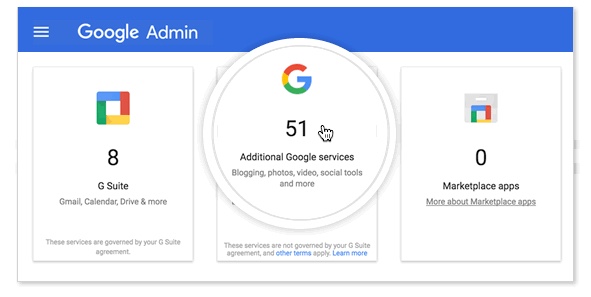

Exclusive Department for Education funding to support schools’ adoption of tech giants[7] products in lockdown, further established their market dominance, and without any transparency of their future business plans or intentions or assurances over service provision and long-term sustainability.

The lasting effects of the COVID-19 crisis on children’s education and the future of our communities, will be as diverse as their experiences across different schools, staff, and family life. Worries over the attainment gap as a result of lost classroom hours, often ignores the damaging effects on some children of the digital divide, deprivation and discrimination and lack of school places for children with SEND, that also affected children unfairly before the coronavirus crisis. Solutions for these systemic social problems should not be short term COVID-19 reactions, but long term responses and must include the political will to solve child poverty. Children’s digital rights are quick to be forgotten in a rapid response to remote learning needs, but the effects on their digital footprint and lived experience might last a lifetime.

We call for urgent government action in response to the COVID-19 crisis and rapid digital expansion:

- the Department for Education to place a moratorium on the school accountability system and league tables as pupil data continue to be affected by COVID-19, making comparable outcomes and competitive measures meaningless and misleading. We suggest a pause on the Early Years attainment profile, and Key Stage One SATs and only sampling Phonics Tests and a sample of Key Stage Two SATS. Reception Baseline Test is not fit for purpose and should be stopped indefinitely, alongside the Multiplications Times Tables Check.

- core national education infrastructure delivered by the private sector should be put on the national risk register as its fragility has been demonstrated in the COVID-19 crisis

- publish a list of actions the Department will undertake in response to the 2020 ICO audit

- build better infrastructure at national, regional and local levels founded upon a UK Education and Digital Rights Act, and give it independent oversight through an ombudsman and champion of children’s rights for national data in education, placed on a statutory footing.

Sector-wide attention and longer term action is needed to address

- Access and inclusion: Accessibility design standards and Internet access and funding

- Data cycle control, accountability and security: mechanisms are needed by industry and schools for lifetime governance and data management for where children leave schools and leave education and that restore lifetime controllership to educational settings

- Data rights’ management: A consistent rights-based framework and mechanisms to realise children’s rights is needed between the child / family and players in each data process; schools, LAs, the DfE, companies, and other third-parties for consistent, confident data handling; right to information, accuracy, controls and objections.

- Human roles and responsibilities: The roles of school staff, parents/ families and children need boundaries redrawn to clarify responsibilities, reach of cloud services into family life, representation; including teacher training (initial and continuous professional development)

- Industry expectations: normalised poor practice should be reset, ending exploitative practice or encroachment on classroom time; for safe, ethical product development and SME growth

- Lifetime effects of data on the developing child: The permanency of the single pupil record

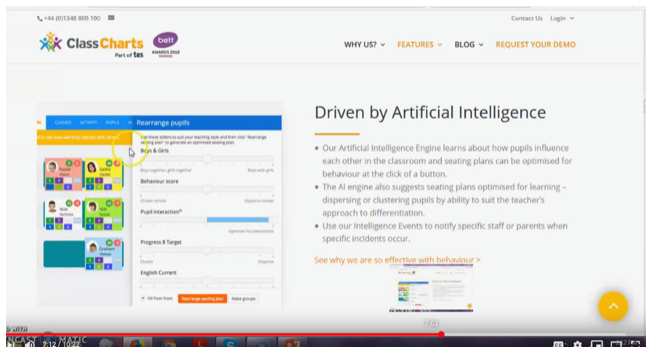

- Machine fairness: Automated decisions, profiling, AI and algorithmic discrimination

- National data strategy: The role of education data in the national data strategy and the implications of changes needed in the accountability and assessment systems

- Procurement routes and due diligence: Reduce the investigative burden for schools in new technology introductions and increase the independent, qualified expert support systems that schools can call on, benefiting from scaled cost saving, and free from conflict of interest

- Risk management of education delivery: Education infrastructure must be placed on the national risk register, reducing reliance on Silicon Valley tech giants and foreign-based edTech with implications for data export management, and increasing transparency over future costs, practice, and ensuring long-term stability for the public sector.

This year marks 150 years since the Elementary Education Act 1870 received royal assent. It was responsible for setting the framework for schooling of all children between the ages of 5 and 13 in England and Wales.

Todays’ legislation, the Education Act 1996 is the primary legislation upon which most statutory instruments are hung to expand pupil data collections, and start new ones for millions of children generally as negative statutory instruments without public consultation or parliamentary scrutiny. It is no longer fit for purpose and lacks the necessary framework when it comes to data processing and related activity in the digital environment in education. It is therefore our first in ten areas of recommended actions on the changes our children need.

In 2020 as the world’s children continue to be affected by school closures in the COVID-19 pandemic, technology plays a vital role in education. Some tools enable the delivery of essential information, connecting school communities outside the classroom. Others provide national platforms for sharing educational materials, or offer alternative means and modes of Assistive Technology and augmented communications, supporting the rights of those with disabilities.

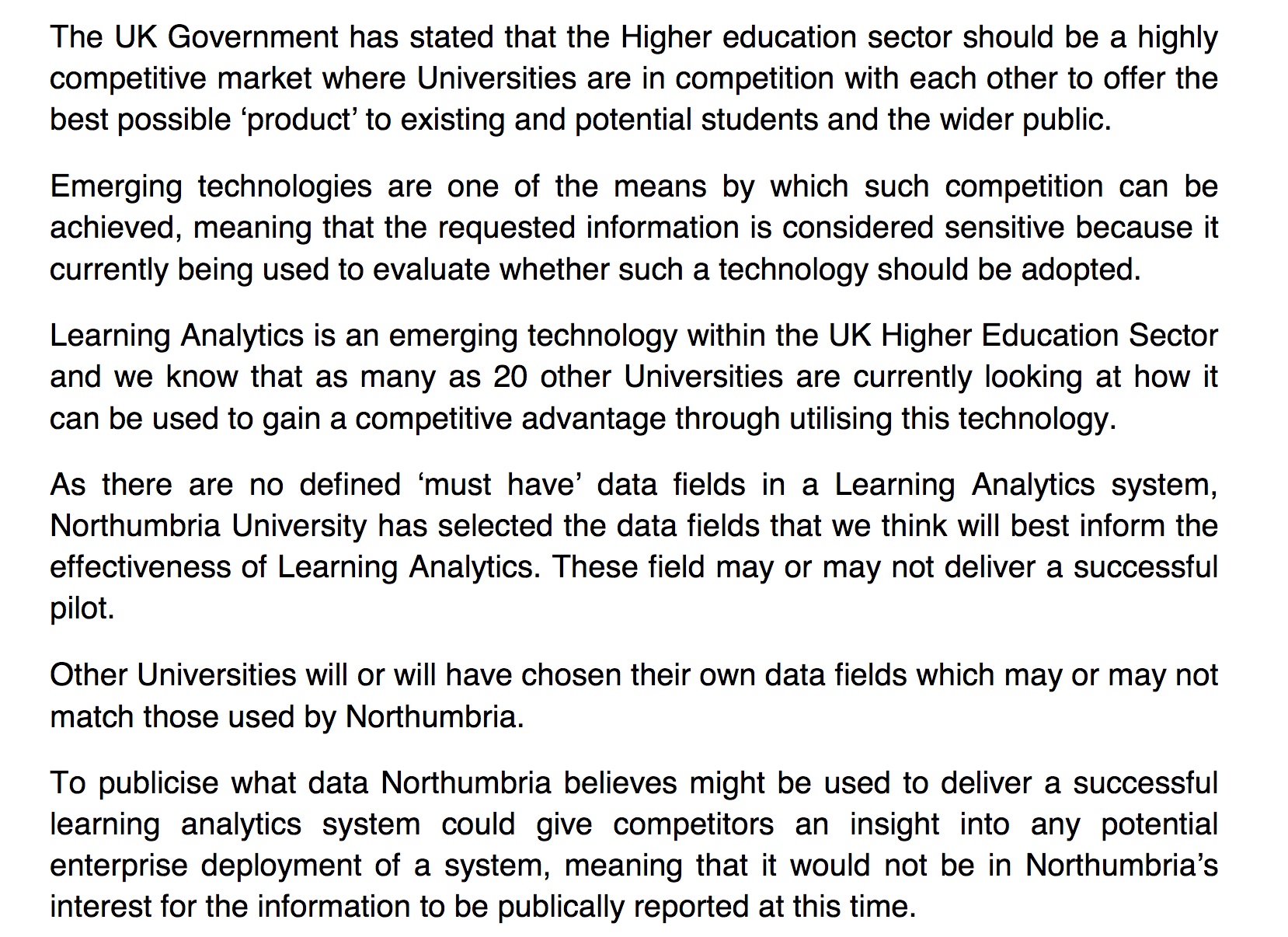

But many families across the UK still don’t have the necessary hardware or Internet access to support online remote learning at home. In addition, a lot of the critical infrastructure to deliver the administrative access to education is enabled by Silicon Valley big tech — companies originally set up by and for business, not educators. The Department for Education’s (DfE) rapid response to a need for remote learning in the COVID-19 pandemic, bolstered the near duopoly in England’s school system by offering funding in the Platform Provisioning Programme, to schools to get started with only two providers’ systems— either Google or Microsoft.[8] Is that lack of sovereignty in the state sector sustainable? What is the current business model? What happens when freeware business models change? There is inadequate capability and capacity in schools to understand much of the technology marketed at them. Staff are expected to make quick and effective procurement choices for which they have often little training and can lack access to the necessary expertise.

Some of the greatest ongoing debates in the education sector on assessment and accountability, funding, curriculum and governance all have implications for children’s digital records. And we are at an acute point of heightened awareness of disadvantage and distance learning. Understanding how technology should support these needs was part of the regular delivery of education. A large part of products offered to schools was for administrative support, but tools supporting learning to date have in the main offered stand-alone and closed commercial product offerings. The exceptional demands of remote learning now demand more focussed attention on what is desirable, not only on what is currently available.

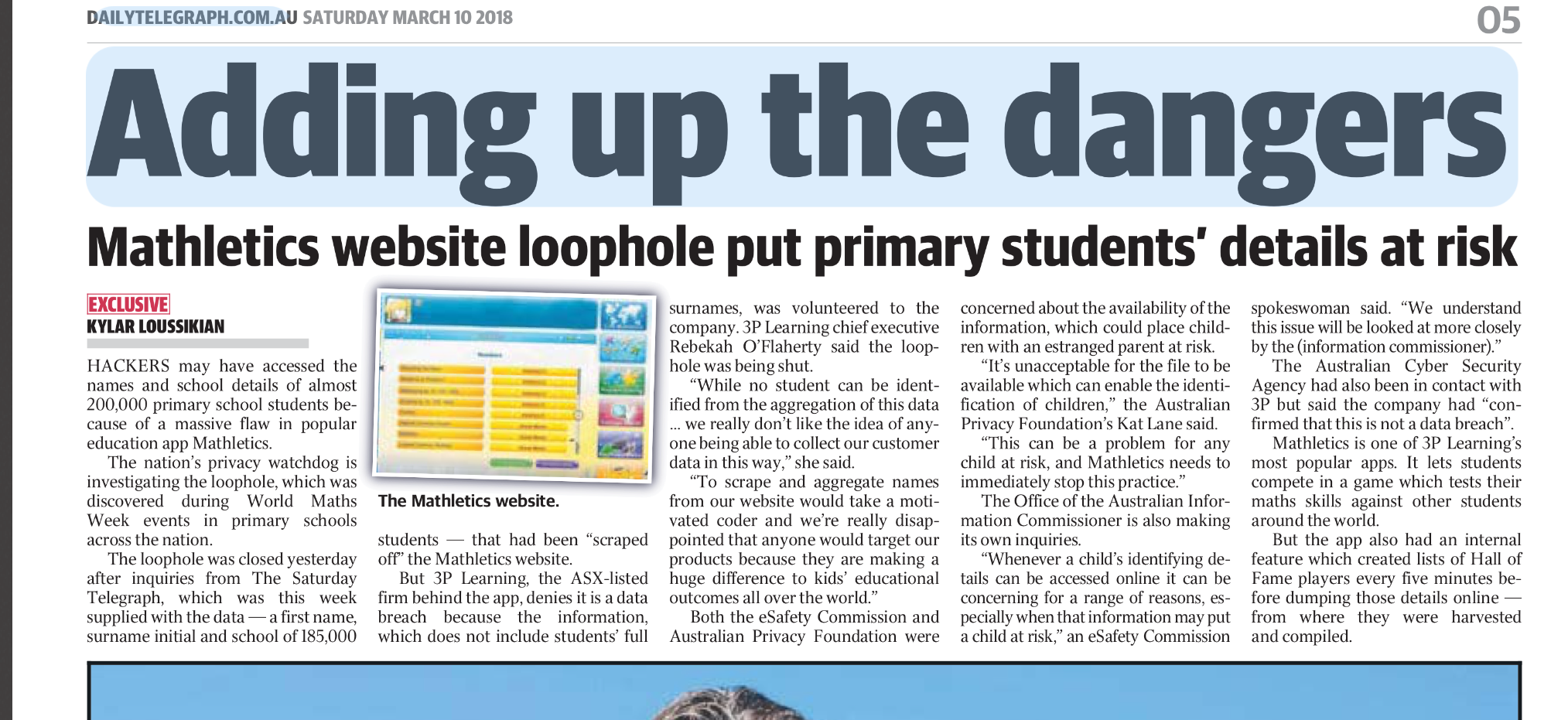

Creating better public sector infrastructure and local systems

Today, schools overstretched by austerity, routinely push costs back to equally cash strapped parents. Lack of investment in school infrastructure means parents are increasingly asked to pay upwards of £400 in lease-to-buy hardware schemes and take on ever more back-office pupil admin through linked pupil-parental apps. Freeware products may choose to make money through data mining or ads instead of charging an upfront fee that schools can’t afford. Children using the product may not know their data and behavioural activity is used as a free resource by companies in product development and research. Practice that can fail to comply with the law.[9]

Imagine instead, a fair and open market in which safe tools were supported that were effective, equitable, and proven to meet high standards. To support better accessibility, pedagogy and provide trustworthy emerging technologies we must raise standards and hold businesses and the state accountable for their designs and decision making.

Imagine if the government invested a flat rate in COVID-19 teacher training support, and open funding to build tools that schools need, to support a blended approach beyond autumn 2020.

Imagine moving away from systems that siphon off personal data and all the knowledge about the state education system—using teachers’ time and work invested in using the product for their own benefit—and instead the adoption of technology focussed on children’s needs and transparently benefited the public interest. Imagine decentralised, digital tools that worked together across a child’s school day centred on the child’s education rather than a series of administrative tools that are rarely interoperable and most often siloed.

Despite the best intentions of peer-to-peer demonstrator schools to share best practice and selected digital products, there is no joined-up vision for a whole curriculum approach, underpinned by pedagogy and proven child outcomes. Promotion encourages adoption of ABC products because it can help you with XYZ as a bolt-on to current practice. Rather than looking at a child-centric and teacher-centric experience of teaching and learning and asking what is needed. While many products look and sound appealing, many of the learning outcomes are contentious and unproven, and are rarely compared with giving every secondary school child a full set of subject text books for example.

Government must work to safeguard the national infrastructure behind the delivery of state education and our future state ability to afford, control, and shape it. But it must also provide a high standards framework for educational settings to be able to address the lack of equity and access at local level; due diligence in procurement in technical, company integrity and ethical terms.

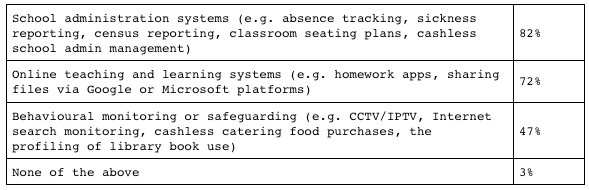

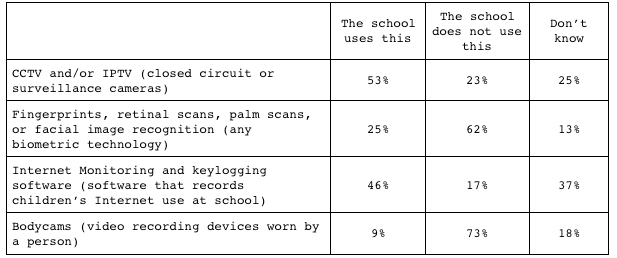

There is rarely a route for families' involvement in decisions that affect their child from high level democratic discussion of the corporate reform of education through to the introduction of technology in education, down to the lack of consultation on the installation of CCTV in school bathrooms. Without new infrastructure, the sector has no route to move forwards to develop a consistent social contract to enable and enforce expectations between schools and families.

Creating safe national data systems

Learners have also found themselves at the sharp end of damaging algorithms and flawed human choices this summer across the UK, as the exam awarding processes 2020 left thousands of students without their expected grades and stepping stone to access university. People suddenly saw that a cap on aspiration[10] was a political choice, not a reflection of ability.

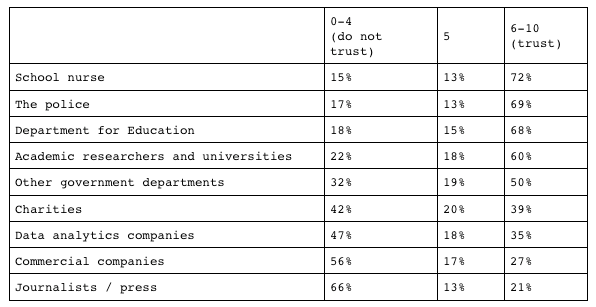

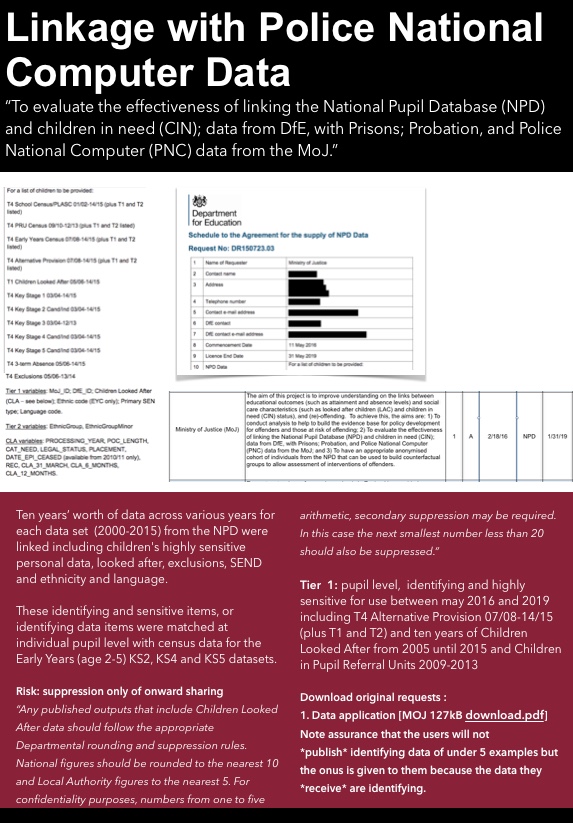

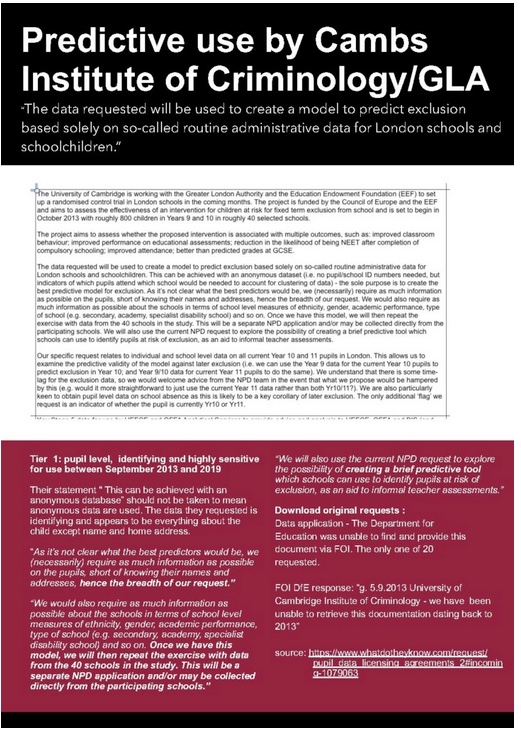

The historic data used in such data models is largely opaque to the people it is about. The majority of parents we polled in 2018 do not know the National Pupil Database exists at all. We have campaigned since 2015 for changes to its management; transparency, security and reuses.

In the wake of the national Learning Records Service breach,[11] the Department for Education tightened access to the approval process for new users of the 28 million individuals’ records in Spring 2020. The Department now requires firms to provide details of their registration with both the Information Commissioner’s Office and Companies House, as well as evidence of their being a going concern. And it will be dependent on firms providing “a detailed description of why they need access” —all of which one would have expected to be in place and that routine audit processes would have identified before it was drawn to national attention by the Sunday Times[12]. But it is just one of over 50 such databases the Department for Education controls, and what about the rest? The ICO findings from its 2020 audit should be applied to all national pupil data.

These databases are created from data collected in the attainment tests and school censuses, some of which didn’t happen this year. So what needs to happen next?

After the exams fiasco 2020, and pause on attainment testing for the accountability system, we propose a moratorium on league tables, accountability, and Progress 8 measures until at least 2025. Delay the national central collection of children’s records and scores in the new Reception Baseline and Multiplications Times Tables Tests. Data should work to support first and foremost the staff that create it in the direct care of the children in front of them. The Department for Education should receive sampled data from Early Years, Phonics and Key Stage Two testing and enable a decentralised model for the minimum necessary information transfers of Year 6 into Year 7 transition, which may adjust the Common Transfer File.

Building a rights’ respecting digital environment in education

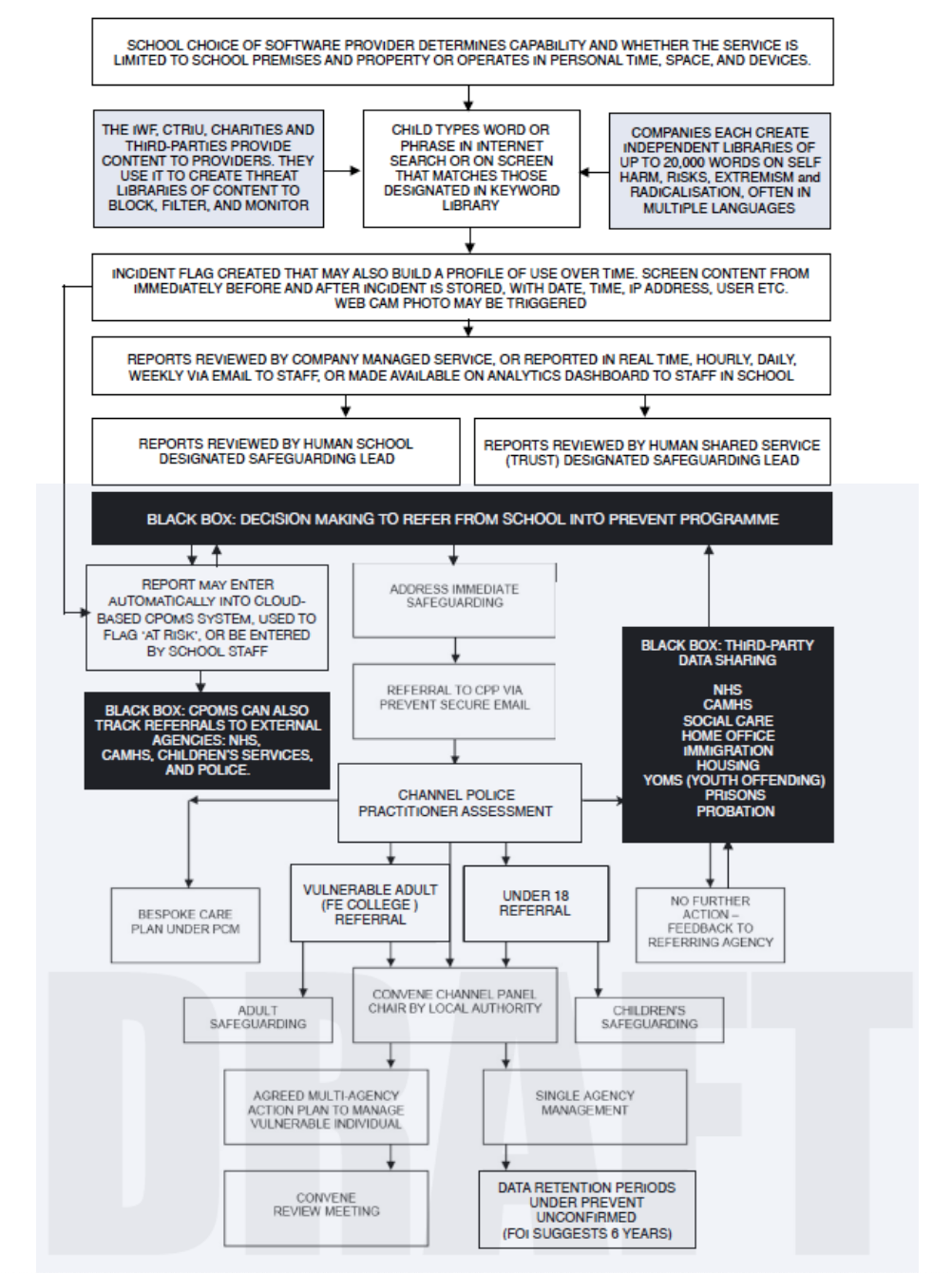

Few families would let an unlimited number of strangers walk into their home, watch what they do on-screen, hear what they say or scan every Internet search and label it with risk factors. No one would let strangers or even school staff take a webcam photo of their child without their knowledge or permission. We would not expect outsiders who were not qualified educators to stand in the classroom and nudge a child’s behaviour or affect their learning without DBS checks, safety and ethical oversight and parents being informed. Yet this is what happens through current technology in use today, across UK schools.

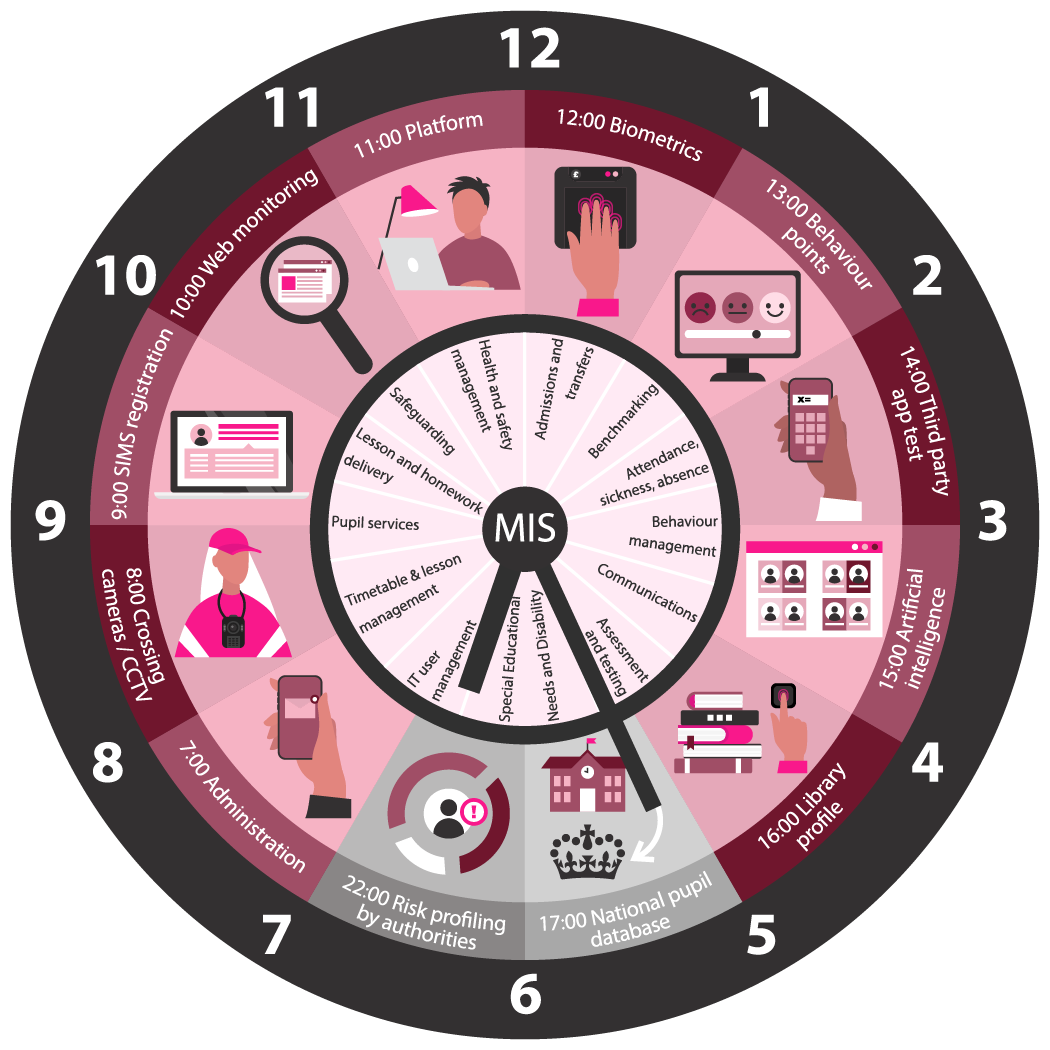

Imagine England’s school system as a giant organisational chart. What do you see? Which institutions does a child physically pass through? How do the organisations relate to one another and who reports to whom? Where is regulation and oversight and where do I go for redress if things go wrong? It is nearly impossible for parents to navigate this real-world complexity amongst the last decade of restructuring of the state school system. Now add to that the world we cannot see. It is hard to grasp how many third-parties a child’s digital footprint passes through in just one day. Now imagine that 24/7, 365 days a year, every year of a child’s schooling and long after they leave school.

Learners’ rights are rarely prioritised and the direction of travel is towards ever more centralised surveillance in edTech, more automated decision making and reduced human dignity and may breach data protection, equality and consumer law.[13] The need for protection goes beyond the scope of data protection law and to the protection of children’s right to fundamental rights and freedoms; privacy, reputation, and a full and free development..

“The world in thirty years is going to be unrecognizably datamined and it’s going to be really fun to watch,” said then CEO of Knewton, Jose Ferreira at the White House US Datapalooza in 2012.[14] “Education happens to be the most data mineable industry by far.”

We must build a system fit to manage that safely and move forwards to meet the social, cultural and economic challenges young people face in a world scarred by COVID-19 and as we exit the European Union. We must not model our future aspirations for the economy and education on flawed, historic data.[15]

We must also enable children to go to school without being subject to commercial or state interference. “Children do not lose their human rights by virtue of passing through the school gates… Education must be provided in a way that respects the inherent dignity of the child and enables the child to express his or her views freely...[16]

The Convention on the Rights of the Child makes clear that children have a specific right to privacy. Tracking the language of the UDHR and ICCPR, Article 16 of the Convention states that “no child shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his or her privacy, family, or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his or her honour and reputation,” and reaffirms that “the child has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks. These standards imply that children should be given the same levels of protection for their right to privacy as adults. When contextualising children’s right to privacy in the full range of their other rights, best interests, and evolving capacities however, it becomes evident that children’s privacy differs both in scope and application from adults’ privacy.” (UNICEF, 2017)[17]

By placing this background work into the public domain (in parts two to five of this report) we intend it for others to use and help keep it up to date with current information and case studies in the constantly evolving areas of statutory data collections and technology to collectively build better.

1.2. Scope of the report Back to top

We set out to map a snapshot of the current state of data processing in 2020 for children in education in England, age 2-19. In Parts 2-4 we describe a selection of some of the common data processing, what systems do and why, how they share data and consider their risks.

This report is about how systems create, use and exploit information collected about children as well as content created by them, and how that data is processed by third-parties, often for profit, generally at public sector cost in terms of school staff time and from school budgets.

We include applied case studies in the online report content (Part 3), brought to our attention by a wide range of stakeholders including young people, parents, state school, private school and public authority staff with the aim of drawing out more concrete discussion of common issues in a rapidly changing field. We are grateful to the companies that contributed to our understanding of their products and reviewed the case studies in advance of publication.

We do not attempt to present this as a comprehensive view of the entire education landscape that is constantly evolving. We need to do further research to map data flows for children with special educational needs who leave mainstream schooling and ‘managed moves’. We do not cover secure children’s homes or secure training centres. But there are consistent gaps with regard to lack of respect for child rights highlighted across Ofsted reports of all settings where children receive education, so that children in the Oakhill Secure Training Centre[18] may have much in common with those in edTech demonstrator schools.

We have sought views from discussion with a wide range of others: academics, benchmarking companies, data protection officers, data consultancies, researchers, school network managers, suppliers, vendors. In 2019 we also ran workshops with young people.

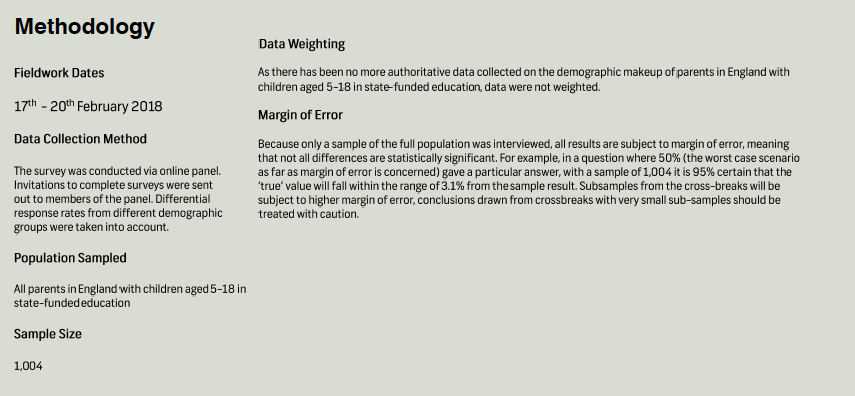

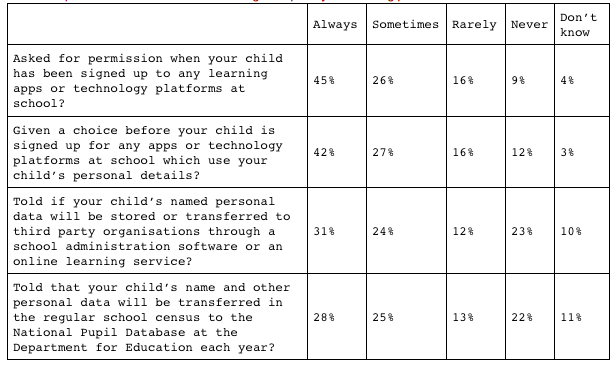

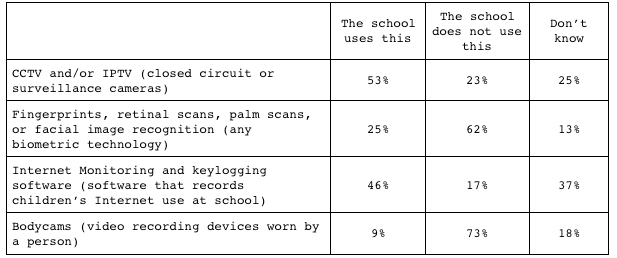

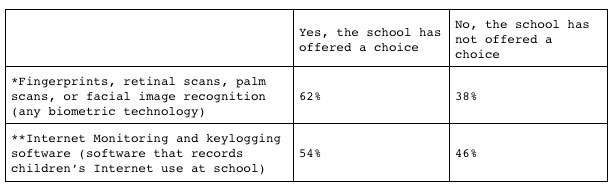

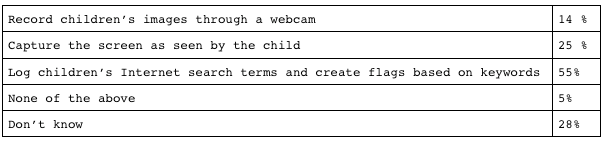

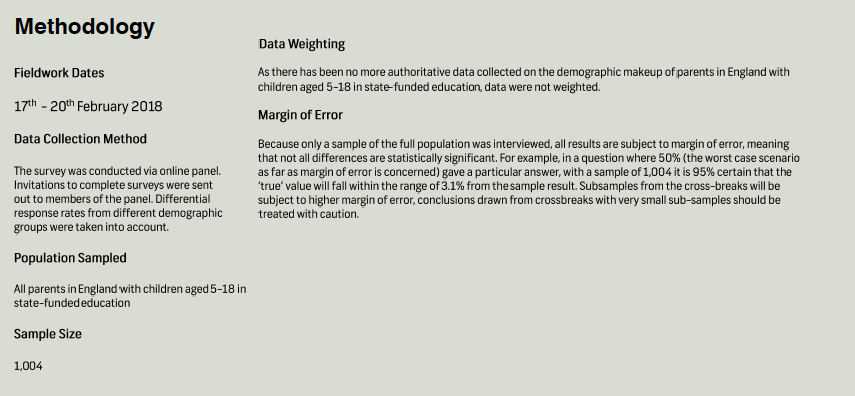

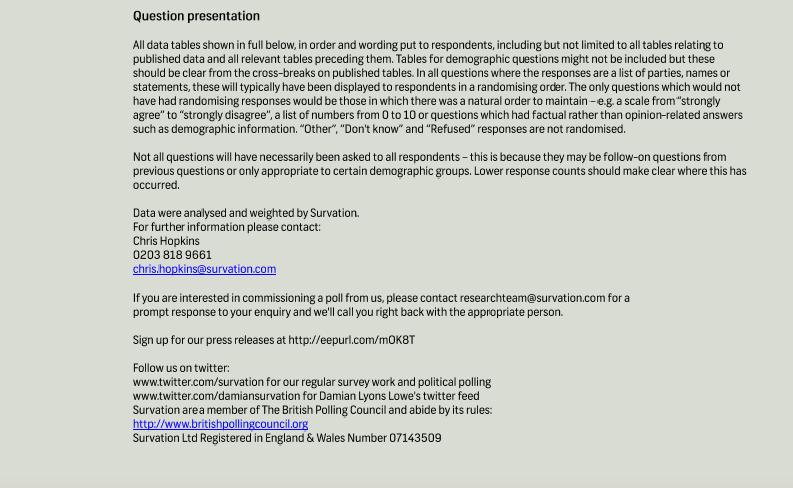

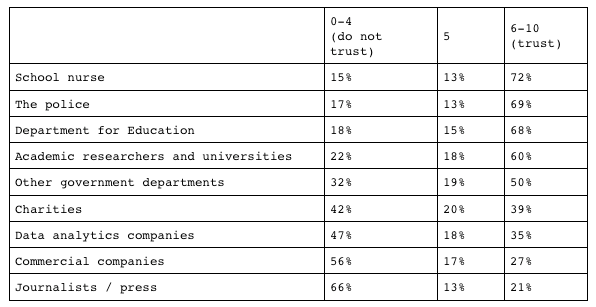

We include the opinions of over 1,000 parents in a poll we commissioned through Survation in 2018, and the views from 35 school IT network managers and staff on the online forum Edugeek, polled just before the GDPR came into enforceable effect in May 2018. The latter was too small to be a representative sample of opinions, but is an interesting snapshot of views in time.

This report is not about how children access or use the Internet in their personal lives. There is already a lot of discussion about child protection with regard to online stranger-danger, or restricting their access to harmful content.

We aim to map what personal data is collected by whom, for what purposes and where it goes and why. This report is only a sample of the everyday data collection from children in the course of their education and tells only some of the story that we can see. The fact that so much is hidden or hard to find is of itself a key concern. Gaps that readers familiar with the sector may identify, may highlight how hard it is for families to understand the whole system. We intend to update this knowledge base in an online repository and maintain it with current examples as time goes on. We welcome case studies and contributions to this end.

1.2.1 The report structure Back to top

This report falls into five parts.

Part 1: a summary report of recommendations and main findings

Part 2: national statutory data collections including a CV at-a-glance age 0-25

Part 3: local data processing including edTech case studies and a day-in-the-life of an eleven year old

Part 4: highlights from the transition from compulsory school to Higher Education

Part 5: an annex of data, source materials, research and references.

This is Part 1 and consists of this introduction and summary report to highlight our ten areas of recommended actions. Parts 2-5 are online only.

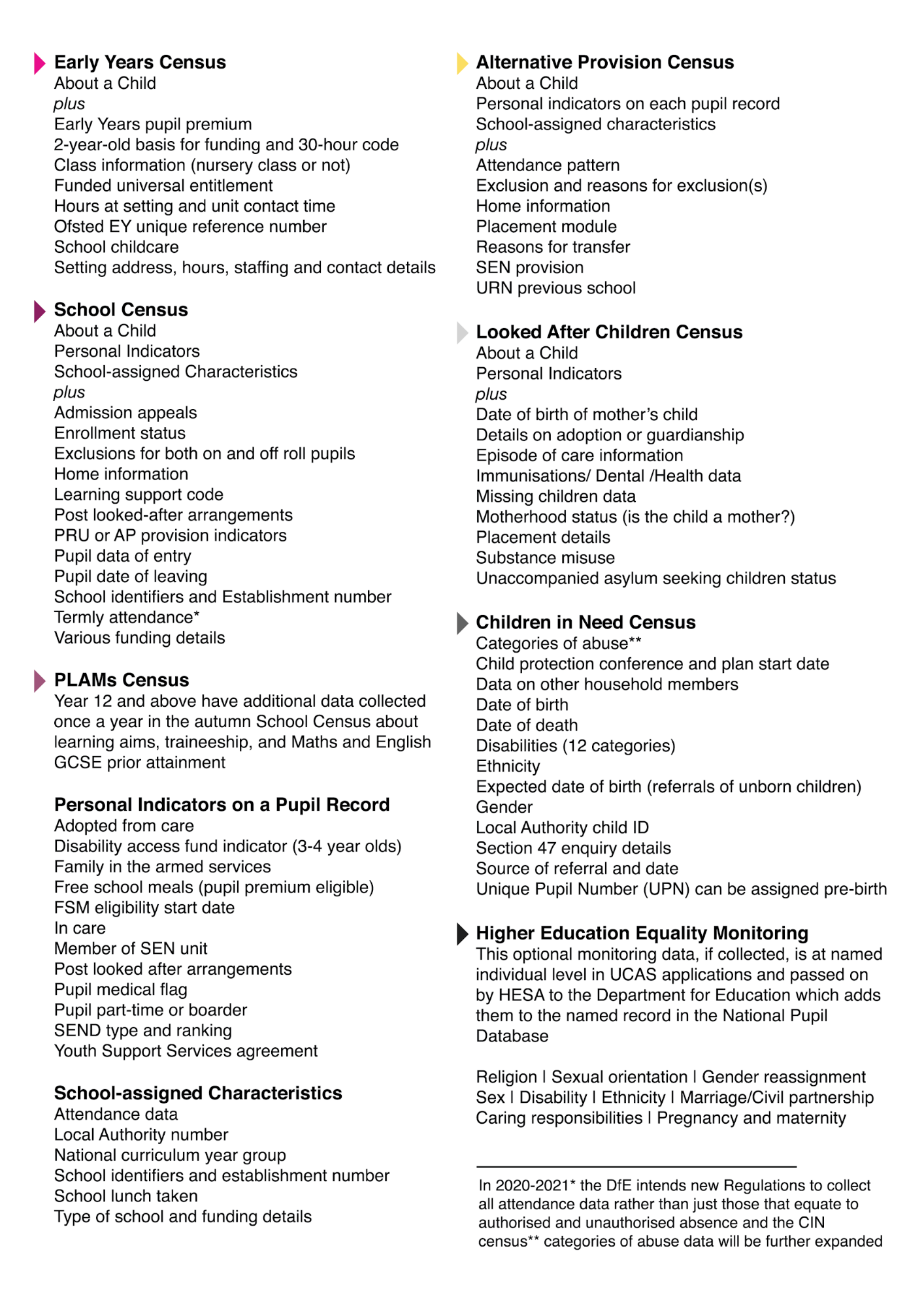

Part 2 starts by identifying the core infrastructure behind national statutory data collections in the state education system affecting children typically from birth to age 25. We mapped the most common statutory data collections for the purposes of the national accountability system that are about recording a child’s attainment and testing and the seven types of census collected by the Department for Education on a termly or annual basis. A subset applies to every child in mainstream education with additional collections for each child who attends state-funded Early Years settings, is a child at risk, or leaves mainstream education and is counted in Alternative Provision. We added in the most common data collections from local level progress and attainment testing for schools’ own purposes and additional testing applied to a sample of children nationally every year for national and international purposes. And we address where all this data goes when it leaves a school and how it is used.

Finally we look at samples of other significant pupil data collected through schools about children nationally, such as health data and the vital role of the school vaccination programme as well as the interactions with school settings by other national institutions for youth work, careers or school regulation by Ofsted.

In Part 3 we address local data processing. We map common aspects of the local data landscape and address the data processing from the daily systems and edTech interactions that affect children from both primary, secondary and further education to help readers’ understand the volume of data flows between different people and other organisations outside the state education sector. We include a range of case studies picking out different types of edTech most common in schools today.

In Part 4, we address in brief, the transition between school and Higher Education, from childhood to adulthood. We look at some of the most common data processing from applicants and students as they transfer from state education to Higher Education at age 18. We cover both national data collections and local institutional choices processing data for student data analytics and national policies such as the Prevent programme.

Part 5 contains an Annex of tables, and figures including comparisons of national data collections and use across the four devolved nations only to serve as a comparison to England’s policy and practice, and while many of the same questions around edTech apply across all of the UK, we do not attempt to map the landscape outside England.

A future and further stage of this project would look to map the Department for Education funding flows across the sector to see where there are differences between who provides data about a child, where the child learns, and who gets the money for providing their education. In researching the Alternative Provision sector in particular the discrepancies indicate a lack of accountability when where a child goes and where the money goes are to different places.

Later guidance will be created from this to help advise teachers and parents of what they can do to protect children’s human rights as we continue to move into an ever-more machine-led world.

1.3. Recommendations and selected findings Back to top

Three futures need to be championed and must be made compatible in a long term vision for a rights’ respecting environment in state education. 1) The rights of every child to education and promotion of their fullest development and human flourishing[19], 2) the purpose and value of learning and education for society and its delivery, and 3) the edTech sector’s aspirations and its place in the UK economy and in export. We must build the legal and practical mechanisms to realise rights across the child’s lifetime and beyond the school gate, if the UK government is to promote all three. It is against this background that we have undertaken this report at defenddigitalme and recommend founding that framework in legislation upon which that vision for the future can flourish.

1.3.1.1 Recommendations One | Legislation and statutory duties Back to top

For national governments

- Legislate for a UK Education and Digital Rights Act to safeguard the infrastructure behind the delivery of state education and our future sovereign ability to afford, control, and shape it.

- An Education and Digital Rights Act, with due regard for devolved issues, would build a rights’ respecting digital environment in education and consider standards for procurement, accessibility and inclusion; address data justice and algorithmic discrimination, and ensure that introductions of products and research projects to the classroom have consistent pedagogical value, ethical oversight, safeguarding, quality and health and safety standards.

- Core national education infrastructure must be put on the national risk register. Dependence on products such as Google for Education, MS Office 365, and cashless payment systems, all need to have a further duty to transparency reporting obligations. We are currently operating in the dark where remote learning is and is not supportable, and about the implications of dependence on these systems for the delivery of key school functions and children’s learning.

- Legislation, Codes of Practice, and enforcement need to prioritise the full range of human rights of the child in education. This should be in accordance with Council of Europe Recommendation CM/Rec (2018) of the Committee of Ministers to member States on Guidelines to respect, protect and fulfil the rights of the child in the digital environment.[20] Stakeholders at all levels must also respect the UNCRC Committee on the Rights of the Child General comment No. 16 (2013) on State obligations regarding the impact of the business sector.[21]

- An Education and Digital Rights Act would govern not only children’s rights to control the access to educational information and records by commercial companies about themselves, but govern rules on routine foreign data transfers and address the implications for the export control, value and security of national public sector created data about our education system through our children’s learning and behavioural data held by private companies, in the event of mergers and acquisitions.

- Accessibility and Internet access is an economic and a social justice issue. As 1 in 4 children lives in poverty[22], this must come before you promote products on top of the delivery systems. Government should extend the requirement on affordable telephony to broadband to help ensure every child has equitable access to the Internet at home and to keep pace with the connected digital economy to support children in-and-beyond the pandemic crisis response.

- Ensure a substantial improvement in the support available to public and school library networks. Recognise that children can rely on public libraries for quiet and private study space, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, notwithstanding current COVID-19 limitations.

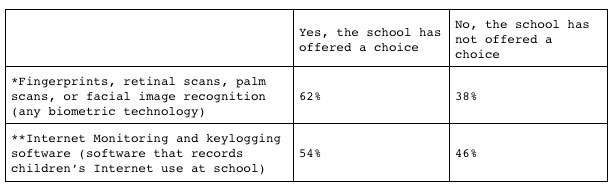

- Ensure consistency across the devolved nations for children’s biometric data protection. A range of biometric data are processed by commercial companies but the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 applies only to schools in England and Wales. Introduce legislation on protections of biometric data in Northern Ireland and Scotland consistent with England and Wales, to protect and fulfil the rights of the child in the digital environment across the public sector.

- Public sector bodies must facilitate mechanisms to explain the Right to Object that accompanies the legal basis under which they carry out most educational data processing under the GDPR Article 6(1)(e) and give families and children a way to exercise it

- Freedom of Information laws should be applied to all non-state actors, companies and arms-length government bodies, as pertains to their educational and children’s services activities commissioned by the publicly funded state sector.

- Under s66 of the Digital Economy Act it is a criminal offence to disclose any personal information [obtained] from administrative data for research purposes. Such activity would already be an offence under s.55 Data Protection Act 1998 if undertaken without the data controller’s consent. (Mourby at al. 2018)[23] This should be applied to third party commercial data processors that are repurposing administrative data obtained from public sector data processing at local level (a child’s pupil data) and disclosing it to third-party researchers that the school did not engage or request that children’s data be repurposed.

- A White Paper should start the ball rolling, to address the sector-wide changes needed, focussed from a people-first and pedagogy perspective. It needs to explore further the rights’ issues raised in the pandemic response such as product design and accessibility, infrastructure access and equality, the lack of social contract between children and their data processors; and staff skills; as well as horizon scanning to identify the necessary secure and sustainable infrastructure and governance models required for a safe, just, and transparent digital environment in education.

For the Department for Education

- A national oversight body is needed on a statutory footing to oversee data governance in education to address the lack and compliance and accountability found by the ICO in its audit of the Department for Education, and issues in the broad use of edTech. A National Guardian for education and digital rights, would provide a bridge between government, companies, educational settings and families, to provide standards, oversight and accountability. Capacity and capability across the sector would further benefit from a cascading network of knowledge with multi-way communication, along the principles of the NHS Caldicott Guardian model.

- Accessibility standards[24] for all products used in state education should be defined and made compulsory in procurement processes, to ensure fair access for all and reduce digital exclusion.

- A national model of competent due diligence in procurement should be developed and the infrastructure put in place for schools to call on their expertise in approved products. Procurement processes must require assessment of what is pedagogically sound and what is developmentally appropriate, as part of risk assessment including data protection, privacy and ethical impact. Assessment of risk is not a one-time state, at the start of data collection, but across the data life-cycle.

- Start with teacher training. The national strategy is all about products, when it should be starting with people. Introduce skills, data protection and pupil privacy into basic teacher training, to support a rights-respecting environment in policy and practice using edTech and broader data processing. This will help to give staff the clarity, consistency and confidence in applying the high standards they need. Ensure ongoing training is available and accessible to all staff for continuous professional development. A focus on people, not products, will deliver fundamental basics needed for better tech understanding and use and provide the human support infrastructure needed to reduce the workload and investigative burden in school procurement.

- Establish fair and independent oversight mechanisms of all national pupil data collected in censuses and standardised testing, so that transparency and trust are consistently maintained across the public sector, and throughout the chain of data processing starting from collection, to the end of its life cycle. Develop data usage reports from the Department for Education for each child, that can be downloaded and distributed by schools annually or on request to show individuals what is held about them by the Department and how it has been used.

- Fix the inconsistency of approach in current legislation that exists between Local Authority and other academy/free schools et al. on the parental right of access to the child’s educational record. Standard reports should also be mandated from school information management systems providers to address the inconsistency of how Subject Access rights are fulfilled by the wide variety of school information management systems. Shift the power balance back to schools and families, where they can better understand what is held about them by whom and why.

- Every company that has a seat at the national Department for Education UK edTech strategy table, or that can benefit from access to public sector pupil data, should also have statutory obligations to demonstrate full transparency over their own sector practices, including business models, extent of existing market reach, future intentions, and meeting data protection law.

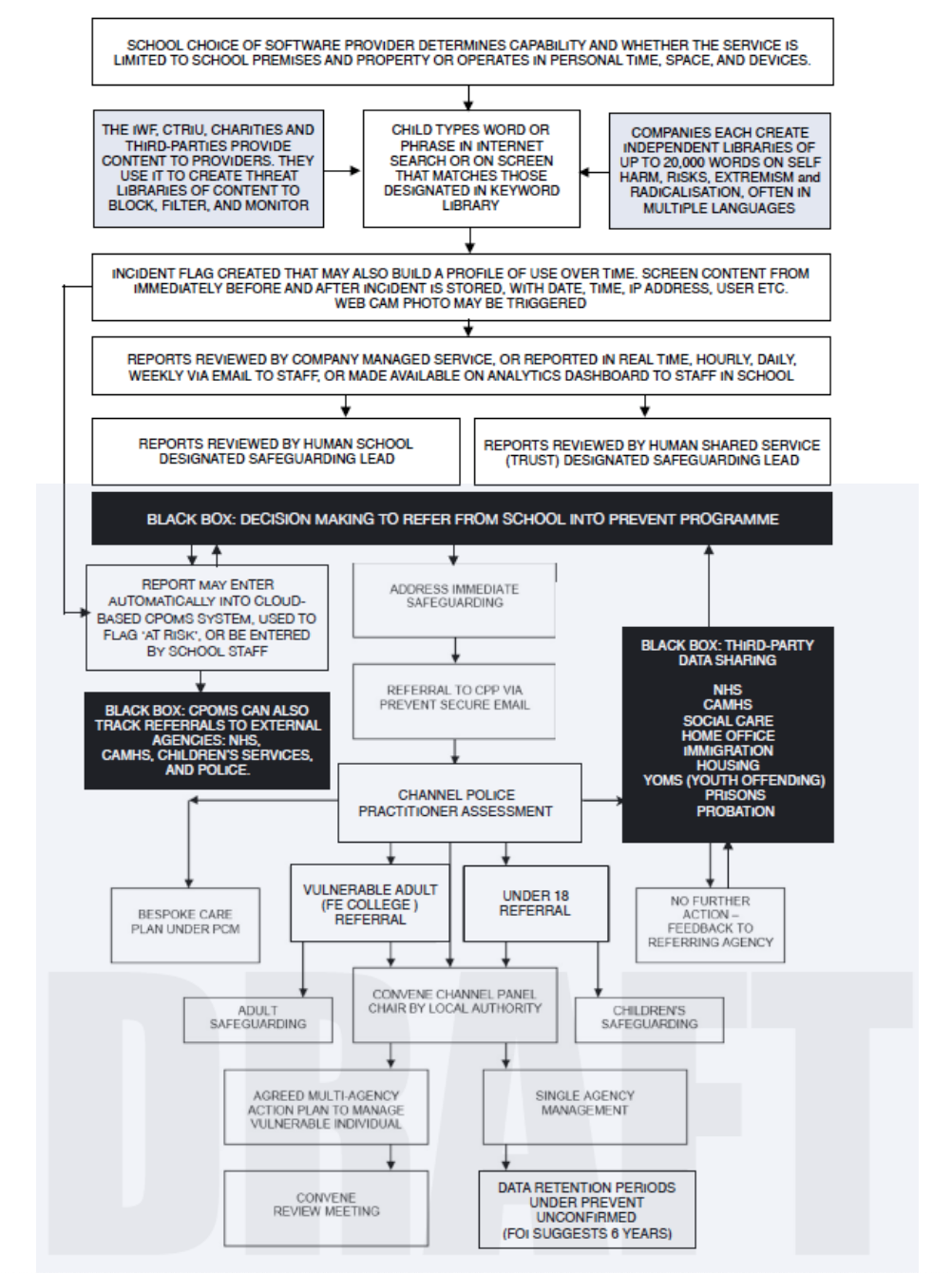

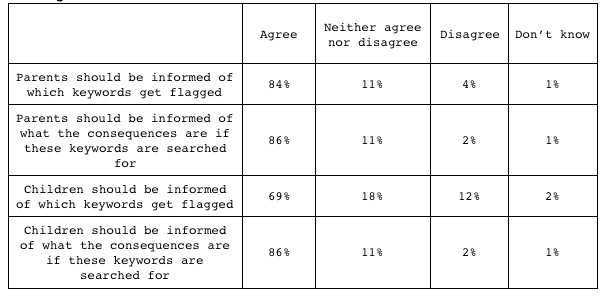

- The Department for Education’s statutory guidance ‘Keeping Children Safe in Education’[25] obliges schools and colleges in England to “ensure appropriate filters and appropriate monitoring systems are in place” but gives no guidance how to respect privacy and communications law or rules on monitoring out of school hours or while at home. This needs urgent regulatory intervention and changes in legislation to prevent today’s overreach that affects millions of children at home in lockdown and while remote learning. (See case studies, part three) Defining safeguarding in schools services and software application standards could begin in the short term as consultation with industry and civil society, and lead to a statutory Code of Practice.

- To ensure respect for the UPN statutory guidance[26] that states the UPN must lapse when pupils leave state funded schooling, at the age of sixteen or older, the Department for Education should clarify what ‘lapse’ means in accordance with the law, for retention and data destruction policies.

For Local Authorities and Multi-Academy Trusts and educational settings

- Public Authorities should have a duty to carry out a Child Rights Impact Assessment before any adoption of large scale or high risk projects involving children’s data obtained through schools. Public Authorities should document and publish a transparency and risk register of such projects, and any data distribution, including commercial processors /sub processors terms of service, any commercially obtained sources of personal data collected for processing.

- Public Authorities should have a duty to document routine large-scale linkage of administrative data processed about individuals in the course of their public sector interactions (Dencik et al 2019) as part of ROPA (GDPR Article 30) and in particular where such data is used for predictive analytics and interventions. Re-use should be made transparent and registers updated on a regular basis. (i.e. Data bought from brokers, third-party companies, scraped from social media) Data Protection Impact Assessments, Retention schedules, Procurement spending on data analytics and algorithm should be published as open data, and GDPR s36(4) Assessments published with regular reviews to address changes to contribute to a improved cumulative national transparency.

- Public bodies at all levels must respect the Right to Object that accompanies the legal basis under which they carry out most data processing under the GDPR Article 6(1)(e). Local Authorities and educational settings must enable consistent ways to explain to children and parents when they have a right to object and offer ways to exercise it and processes to make the balancing test and communicate its outcome, where it applies when processing personal data under the public task at all levels.[27] (GDPR Articles 6(1)e, 9, and Recitals 69 and 70). Staff must be trained on their obligations and how to fulfill them.

- All educational settings must have a statutory entitlement to be able to connect to high-speed broadband services to ensure equality of access and participation in the educational, economic, cultural and social opportunities of the world wide web.

- Ensure respect for the UPN statutory guidance[28] in retention and data destruction policies that states the UPN must lapse when pupils leave state funded schooling, at the age of sixteen or older.

- Furthermore, the UPN must be a ‘blind number’ not an automatic adjunct to a pupil’s name. It must be held electronically and only output from the electronic system when required to provide information to:

- Local authority

- central government

- another school to which the pupil is transferring

- a third party (for example, a supplier of a schools management information system) who have entered into an agreement to provide an education service or system to a school, local authority or government department and process data on their behalf

- A pupil’s admission number, rather than the UPN, must be used as the general pupil reference number on the admission register or paper files.

- The sharing of UPN data with a third party for work or a service not commissioned by the school, local authority or another prescribed person is not permitted nor would the sharing of UPN data for any purposes not related to education.

1.3.1.2 Findings 1 | Legislation and statutory duties Back to top

- Nesta proposed in its 2019 report, Educ-AI-tion Rebooted?[29] that the Government should publicly declare an ambition to create a system of responsible education data sharing by 2030. That somewhat suggests that they believe we do not have one today. We agree with both positions but suggest that 2030 is too far away and the governance framework must start to be built with urgency.

- The State delivery of education cannot reliably depend long term on the planning of private providers, or their free-for-first-three-months offers, to deliver critical educational infrastructure on which both the public sector and the ability to go-to-work of millions of parents rely.

- Rapid response by the Department for Education to support schools without any remote learning platform was exclusively supportive of the ‘Big Two’ Google and Microsoft, and indirectly supported their market foothold. Yes,” many educational settings lack the infrastructure” but that should never mean encouraging ownership and delivery by only closed commercial partners. The current route risks the UK losing control of the state education curriculum, staff training and (e)quality, its delivery, risk management, data, and cost controls.

- At national level there is no independent oversight of how any data infrastructure at local and regional school level is managed. The delivery of education fails to appear on the national risk register despite its brittleness and the problems in its vulnerability caused by remote learning demands in response to the shock of the COVID-19 pandemic. Who owns and has responsibility for the infrastructure? How much is dependent on Silicon Valley and what is known about future ownership, stability, security and costs? Where is it inadequate? Does it meet national needs from the child’s educational perspective? What plans exist if a company that provides its products plus teacher training for free today, nationwide, starts charging tomorrow?

- It is not within OSR’s current remit to regulate the operational use of algorithmic models by the government and other public bodies. Where this regulation should sit needs to be decided and put on a statutory footing after the review of the 2020 exams awarding process.

- Questions of accountability, funding and data are inextricably linked, but when it comes to managing the digital child, there is often confusion over who is responsible for what information when. And the sensitivity of digitized pupil and student data should not be underestimated.[30]

- To guard against Department for Education reputational risk and if the national edTech sector is to be successful in its home grown support of children’s learning and administration as well as in an export strategy, national and local level changes are needed to ensure product integrity and safety standards are achieved.

- Data protection law fails to take account of emerging technologies that process information about children’s bodies and behaviour but that do not meet the definition of biometric data. Data protection law alone cannot offer children adequate protections when it comes to product trials and research trials or controls, involving children without parental consent.

- Data protection law is insufficient to protect children’s full range of rights in the digital environment. Only by reshaping the whole process for the long term, will we have a chance to restore the power balance to schools and to families. Schools must return to a strong position of data controllers and delegate companies to data processors with consistent standards on what they are permitted to do. That infrastructure may not exist, but we need to build it.

- Start with designing for fairness in public sector systems. Minimum acceptable ethical standards could be framed around for example, accessibility, design, and restrictions on commercial exploitation and in-product advertising. This needs to be in place first, before fitting products ‘on top’ of an existing unfair, and imbalanced system to avoid embedding disadvantage and the commodification of children in education, even further.

- While the government is driving an edTech strategy for post-Brexit export, it fails to adequately address fundamental principles of due diligence. This needs to go beyond questions of data protection which is a weak protection for children, disempowered in the domestic public sector environment. A child rights framework is needed to ensure high standards generate the safe use of UK digital products worldwide, not only in the school life of a child, but for their lifetime.

- Finding a lawful basis for children’s personal data processing for many emerging technologies is a challenge. For example, many apps’ and in particular AI companies’ terms and conditions may set out that they process on the basis of consent. But children cannot freely consent to the use of such services due to capacity and in particular where the power imbalance is such that it cannot be refused, or easily withdrawn. “Public authorities, employers and other organisations in a position of power may find it more difficult to show valid freely given consent.” (ICO)

- Consent and contract terms must be rethought in the context of education and for children and their legal autonomy at age 18 and clarified with schools. As set out by the European Data Protection Board in 2020 Guidelines on consent[31], children [and their guardians] cannot freely consent to data processing, where the nature of the institutional-personal power imbalance means that consent cannot be refused, or easily withdrawn without detriment, and they recognise that the GDPR does not specify ways to gather the parent’s consent or to establish that someone is entitled to perform this action or how consent should expire from parents and be asked of a young adult.

- There are also problems with understanding the shared roles of child/parental consent that data protection law fails to address for educational settings where processing is primarily part of a public task. Collecting flawed consent is routinely used as a tick box exercise, and not the proper communications process that it should be to explain what tool is used, how and why.

- At the local level the proliferation of apps used in educational settings for administrative purposes, or to support learning and special needs or wellness interventions has no oversight. Although many digital tools market themselves as meeting Ofsted standards or to help schools do well in inspections, the Inspectorate plays no role in the standards of digital rights or safety and these marketing claims may be baseless when the regulator has not approved them.

- One academy Trust cites over 85 third-party companies and organisations in a non-exhaustive list that interact with children’s daily lives, some of whom will in effect also have access to ‘peer into parents’ phones’ too, when they use the parent app to view children’s school records, update the cashless payment system, notify school of absence or view the behaviour-points their child earned that day.[32]

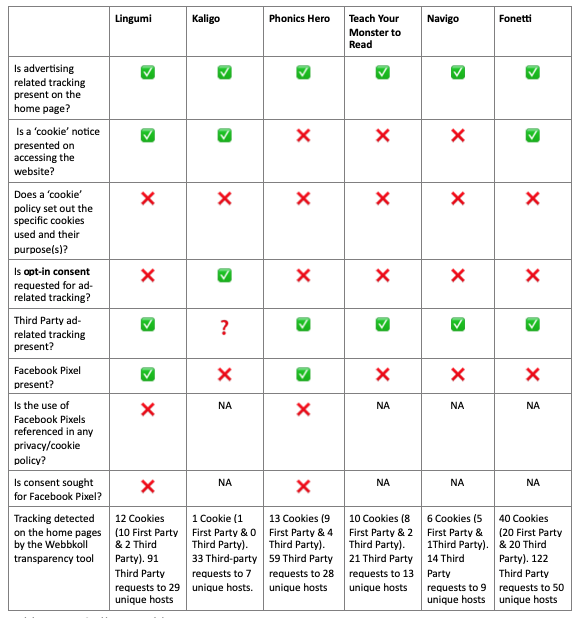

- While schools must only hire staff to work with children after DBS checks and due diligence, anyone can set up a technology company without financial background or safety checks and get into children’s lives and seek to influence them online without any independent oversight. Some edTech can be very intrusive but in ways that may not be apparent to parents. Some products can take photos via a child’s webcam. Some digital tools enable companies to find out about children’s mental health and identify the most vulnerable; and the companies then seek to engage in life-long relationships with millions of children who were required to use the product simply because they went to a school that chose to let them into the children’s lives.

- With no minimum pedagogical or safety standards, hundreds of apps and platforms can influence which books a child will read, shape if they like a subject or not, determine what behaviours are profiled. They can advertise straight to parents’ mobile phones to influence their personal choices or pitch upgrades from the free product the school chose to use, to the premium product that parents pay for. While some tools offer parental portals they often focus on presenting their own perceived added value: dashboards, monitoring reports and even giving parents copies of children’s every move, an itemised list of food and drink bought in the canteen, or behaviour recorded in school systems.

- None offers sufficient insight into how the company behaves or shows how the child’s data they process is shared with affiliated companies, sets out what advertisers parents should expect to see on their mobile phones, or how algorithms use a child’ data to monitor or predict their behaviours and influence a child’s educational experience.

- The constant commercial surveillance of our online behaviours that the adTech online advertising industry is built on; knowing when you use a product, for how long, where you click, which pages you stay on and where you go next online when you leave an app; is deeply embedded in much of the edTech industry. As set out in the UNICEF issue brief no.3 in August 2020 on good governance of children’s data, government policies in countries around the world offer only limited protections for young people in this expanding, commercialized media culture. (Montgomery et al. 2020)

- The values and educational vision that sit inside products are hidden in black-box algorithms embedded in a child’s daily school life in the classroom and beyond, as a result of school-led procurement. Algorithms with hidden biases and unintended consequences are used in educational settings from low-level decisions, such as assigning class seating plans based on children’s behavioural scores to shaping their progress profiles every day. AI might be shaping an adaptive curriculum or assigning serious risk classifications about Internet activity.

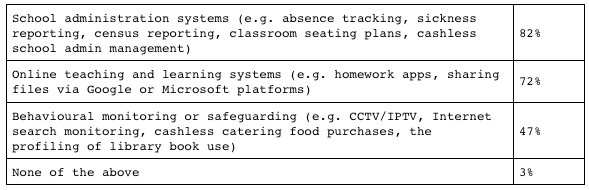

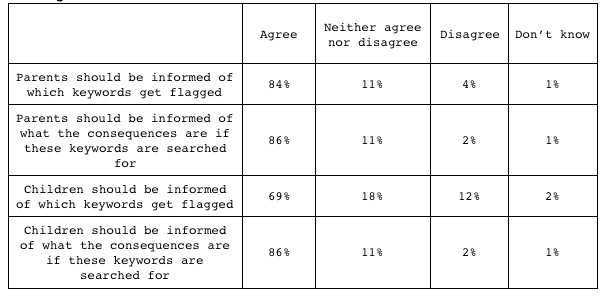

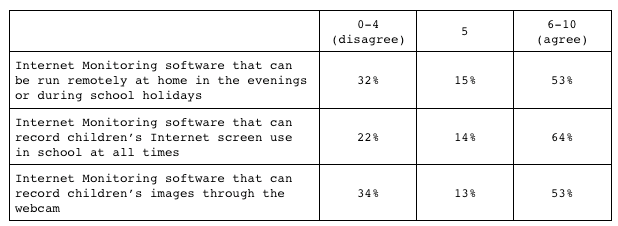

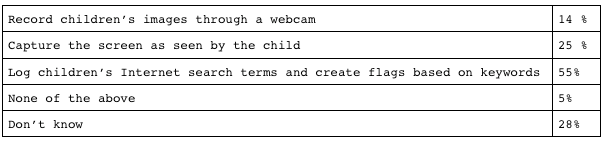

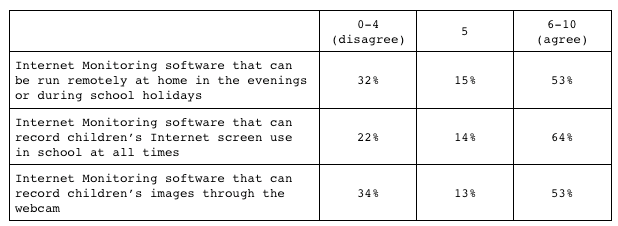

- Internet monitoring that operates whenever a child, teacher or school visitor connects to the school network or GSuite environment, can surveil screen content and searches, by analyzing everything the user types or receives on their device, even passwords[33] including on personal devices depending on the school policy and provider of choice. Some systems can capture text every thirty seconds until the user has stopped or performed an action. If the device is offline, text capture might be sent as soon as it reconnects. Some use AI to match what is typed on-screen with thousands of keywords, which can even include items a child subsequently deletes, suggesting that a child is a risk to themselves or to others, or at risk from radicalisation and label a child’s online activity with ‘terrorism'. Many of the monitoring may continue to work out of school, offsite and out of hours as long as the connection to the school network or GSuite environment remains. Most families we polled in 2018 do not know this. Or know that their child’s on- and offline activity may continue to be surveilled remotely through school software, devices or services during lockdown, or routinely at weekends and in the summer holidays.

- The UNCRC Committee on the Rights of the Child General comment No. 16 (2013) on State obligations regarding the impact of the business sector require that:

“a State should not engage in, support or condone abuses of children’s rights when it has a business role itself or conducts business with private enterprises. For example, States must take steps to ensure that public procurement contracts are awarded to bidders that are committed to respecting children’s rights. State agencies and institutions, including security forces, should not collaborate with or condone the infringement of the rights of the child by third parties. States should not invest public finances and other resources in business activities that violate children’s rights.”

- The use of biometrics is not routinely permitted for children in other countries as it is in the UK.

- Putting high standards and oversight of these sensitive processes in place would not only be good for learners. Schools need clarity and consistency, to have confidence in using technology and data in decisions. Companies big and small, need a fair, safe, and trusted environment if a sustainable edTech market is to thrive.

- An alternative model of data rights’ management in education works in the U.S., governed by FERPA with local state variations. It offers a regional model of law and technical expertise for schools to rely on, with standard trusted contractual agreements agreed at the start of a school year on a regional (State) basis with technical expertise appropriate to the necessary level of due diligence edTech can demand.

- Schools are data controllers. Processors cannot change terms and conditions midway through the year, without agreed notification periods, and reasonable terms of change.

- Families get a list each year (or at each school move) to explain the products their child will be using and legal guardians retain a right to object to products.

- Schools are obliged to offer an equal level of provision via an alternative method of education, so that objection to the use of a maths quiz app is not to the detriment of the child and they do not miss out on teaching.

“In the U.S. Between 2013 and 2018,40 states passed 125 laws that relate to student privacy. In general, these have coincided with states moving to online statewide testing (which has increased the quantity of data created and shared) and as states have built integrated data systems that combine data from multiple state agencies. Some common goals of these laws are

- building upon FERPA and PPRA by further restricting what student data a school can collect or share with others

- providing further requirements and guardrails related to student data shared with websites, online services, and applications

- designating a chief privacy officer and other individuals at the local level responsible for ensuring compliance with privacy laws

- requiring more transparency about what data schools collect and what it is used for

- requiring that schools and vendors meet certain data security standards

- requiring notification to parents in the event of a data security breach.” (Student Privacy Compass, 2020)[34]

- There is a public demand for greater accountability from technology companies. Two thirds asked in the DotEveryone survey for the People, Power and Technology the 2018 digital attitudes report[35] said “the government should be helping ensure companies treat their customers, staff and society fairly. People love the internet—but not at any cost. When asked to make choices between innovation and changes to their communities and public services, people found those trade-offs unacceptable.”

- The Library and Information Association has pointed to the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy figures of a net reduction of 178 libraries in England between 2009-10 and 2014-15.[36]

- Educational settings rarely respect the Right to Object that may apply when processing personal data under the public task ‘in the exercise of official authority’. This covers public functions and powers that are set out in law; and there are no mechanisms for schools to communicate when and why the right applies, the process, or for children and families to exercise this right in national statutory data collections or the collection of local administrative data or in digital tools that process data for marketing. (GDPR Articles 6(1)e, 9, and Recitals 69 and 70.)

- Due to inconsistent legislation, parental access rights to your own child’s school records is not standardised for children across all settings as regards rights to the educational record and inconsistent between Local Authority and academies and other models of education.[37]

- Standard reports to meet data protection law vary wildly between school information management systems providers and generate inconsistency in how Subject Access Rights are fulfilled by a wide variety of settings. Schools can struggle to meet SARs due to the way in which information is managed, and some offer limited system ability to generate legally required documents. In a quid pro quo for MIS providers to access the public sector they should be required to demonstrate a high minimum standard requirement to support schools’ needs.

1.3.2.1 Recommendations Two | Assessment, Attainment, Accountability and Profiling Back to top

While many may consider the middle of a pandemic not the best time to restructure school assessment, progress, and accountability measures, it is inevitable since some of the mainstays of the system do not exist for some year groups after their cancellation under COVID-19. The Department for Education Data Management Review Group 2016 findings are yet to be realised, so that schools can have greater freedom to balance professional autonomy and agency against the demands of the accountability system. And the recommendation from the 2017 Primary Assessment enquiry has not been realised to ensure the risks “of schools purchasing low-quality assessment systems from commercial providers” are mitigated against through standards’ obligations. This year’s awarding process and its failure of fitness for purpose also demonstrates a need for better risk assessment and understanding of the potential for discrimination in data, across all of these systems at all levels.

For the Department for Education

- Urgent independent statistical assessment must be made of the modelling using Key Stage 2 and GCSE prediction reference grades for the 2021 GCSE exam awards process, and the A-levels grading system, including assessment for bias and discrimination in data and design. Obligations on algorithmic explainability need met in ways that meet student needs in plain English and we propose an individual level report that educational settings (exam centres) can download that will demonstrate any data sources, calculations and how each grade was awarded at individual level. The Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) Review may wish to address this.

- The Department for Education should place a moratorium on the school accountability system and league tables 2020-25 while an assessment is carried out on fitness for purpose.[38] Recognising where pupil data will continue to be affected by COVID-19 making comparable outcomes and competitive measures meaningless and progress measures may be misleading, this means a pause on EYFS, Baseline, MTC, KS1, and only sampling Phonics and a sample population could sit the KS2 SATs or alternative assessment where preferable.

- Support 2021+ Primary into Secondary school transition beyond the national sampling of KS2 SATs scores, with KS2 SATs or similar year 6 assessment used for local area use only, in context, and for school transfers, building a fair and lawful decentralised data model, based on the six-into-seven principles, allowing staff to concentrate on children’s local needs.[39]

- Carry out an independent national review and a Child Rights Impact Assessment of the state school accountability, local and national progress measures, and benchmarking models— including those designed by commercial providers and sold to the public sector— to assess for lawfulness and safeguards to prevent harm from individual profiling (aligned with the GDPR Article 25 and recital 71) since such measures ‘should not concern a child’.

- The Department for Education should correct its national guidance,[40]”There Is no need for schools to share individual Progress 8 scores with their pupils”. This instruction from the Department for Education leads to unfair data processing practice by schools in breach of the first data protection principle.

- The Reception Baseline Assessment should not go ahead. It must be independently re-assessed for compliance with data protection law and algorithmic discrimination in a) its adaptive testing model design b) Right to Object c) the plans for seven-year score retention and d) decision to not release data to families. The pilot and trial data were not collected with adequate fair processing.

- Who watches the watchdog? All reuse of historic datasets for regulatory overight by Oftsed should be independently assessed for discrimination as identified in the 2020 exams awarding process. While it is not within OSR’s current remit to regulate the operational use of models by the government and other public bodies where this regulation should sit needs to be decided and put on a statutory footing.

- Every expansion of the seven school censuses and standardised testing should require public consultation and affirmative procedure before legislation can expand national data collections

- The recommendation from the 2017 Primary Assessment enquiry has not been realised to ensure the risks “of schools purchasing low-quality assessment systems from commercial providers” are mitigated against through standards obligations.

- Teacher training in statistics and understanding bias and discrimination in data is required to inadvertently perpetuate any historical bias in schools data that staff have to interpret, including socio-economic, ethnic, and racial discrimination.

- Right to explanation and fair processing must become routine and realised across all school settings. Attainment test results and progress measures must be made available to pupils and families and cannot be carried out in secret or the results black-boxed (aligned with the GDPR Articles 12-15, 22(2)(b) and 22(3)). A standard process must be designed to enable this two-way communication and offer meaningful routes to address questions and seek redress.

- Privacy and Data Protection Impact Assessments should be routinely carried out and published before any new national test, new data collection or new processing aim is announced, especially where it concerns profiling, sensitive data types or the use for punitive purposes. The assessment should be independent from organisations involved as data users and be published. (aligned with the GDPR Article 22(2)(b)).

1.3.2.2 Findings 2 | Assessment, Attainment Profiling and Accountability Back to top

- The summer 2020 exams awarding process was always going to be hard. But then it resulted in the Prime Minister making claims about mutant algorithms and the resignation of the Chief Regulator of Ofqual. Its risk assessment[41] was signed off only a day before the publication of GCSE results which appears odd given it is after any data processing was carried out.

- There were no Key Stage 2 SATS tests and yet primary age children have successfully transitioned from year six into seven. There was no accountability sent to the Department for Education. Although there are no progress 8 measures calculated for this year’s cohort, teaching and learning continues.

- The pause on standardised testing in 2020 shows that it is possible. Leckie and Goldstein (2017) concluded in their work on the evolution of school league tables in England 1992-2016: ‘Contextual value-added’, ‘expected progress’ and ‘progress 8’ that, “all these progress measures and school league tables more generally should be viewed with far more scepticism and interpreted far more cautiously than they have often been to date.[42] With respect for the late Harvey Goldstein perhaps it is the right time like no other, for the government to recognise his 2008 assessment of school league tables. They are not fit for purpose.[43]

- Progress 8 was intended to measure the impact a secondary school has on a pupils' performance across eight subjects. It uses the Key Stage Two results of pupils in their last year at primary school as a starting point. It is a flawed and unsuitable measure of individual ability at age 10 designed as it is to measure system accountability, and almost certainly of dubious value to repurpose for reference in GCSE grade modelling, through its reinforcement of feedback loops.

- Gaming the system by primary schools or parents, can affect the results for those pupils and therefore the accountability measure as a “value-add” of the secondary school. Pupils may not go on to measure up to their expected attainment level, between age 10-11 and GCSEs taken at age 16. Judging secondaries by Progress 8 is therefore a mechanistic but rather meaningless measure, and it is commonly accepted that some primaries data is inflated through above average test preparation by the school or parents beyond what may be expected.

- All pupils with KS1 results are slotted into PAGs alongside thousands of other pupils nationally. The DfE then takes in all the KS2 test scores and calculates the average KS2 score for each PAG. The result is a made-up metric distorted by the pressures of high stakes of accountability. (Pembroke, 2020b)

- Without teacher training in statistics and understanding bias and data discrimination, teaching staff are likely to inadvertently perpetuate any historical bias in the data they have to interpret. Given the significance of carrying out assessment it is a big gap in teacher training, as Dr Becky Allen told the Education Select Committee Enquiry on primary assessment in 2017, that “we do not have a system of training for teachers that makes them in any way experts in assessment”. Some schools had resorted to buying commercial options of varying quality, as described by the Association of Teachers and Lecturers concerned about several dubious “solutions” commercially available to schools which do not offer value for money or a high-quality assessment framework. It was proposed in 2017 that the risks “of schools purchasing low-quality assessment systems from commercial providers” are to be mitigated by high quality advice and guidance, rather than change of policy and practice. That recommendation from the enquiry into Primary Assessment has not been realised and must be with strengthened standards requirements.

- Children and parents have the right to obtain human intervention in any automated decision making, to express his or her point of view and to contest the decision. Accountability measures that routinely profile a child fail to address these rights today, and furthermore require change to build human safeguards into the process so that any errors are easy to identify, the outcomes easily understood by the staff and parents, and any effects as a result explained to both. Fair processing is required to explain what data has been collected and how it will be processed.

- Individuals have rights to access data, and request correction of inaccurate personal data. A person has the right to object, on grounds relating to his or her particular situation, at any time to processing of personal data concerning him or her which is based on either the GDPR Article 6(1)(e) processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller; or (f) processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child.

- The Department for Education Data protection: toolkit for schools (2018)[44] fails to inform schools to apply this right to all statutory high stakes testing and school census data collections, how to do so, or provide any mechanism for families to make an objection to the Department for Education as the data controller.

- This applies to all data processing across the collections in the accountability system and must be applied in the case of the Reception Baseline Assessment as well as to all other statutory high stakes tests and school census data collections.

- The Reception Baseline Assessment has a number of significant problems with the test approach as regards data protection law and in its design. It is problematic from an equality and disability rights perspective given that the same approach is not inclusive for all. When we reviewed the Data Protection Impact Assessment for the Baseline Test,[45] we found it omitted many of the risks including its adaptive test design, omitted that reasons for not taking the test were collected, and did not mention how data may be accessed by third parties from the National Pupil Database. We have been unable to get an answer from the NFER or Department as at September 2020, how they believe it meets the full range of legal obligations of UK data protection law. We were told by an NFER spokesperson in September 2020, that the Department is currently reviewing the DPIA and the privacy notices in advance of the assessment becoming statutory (in 2021). Given the DfE release of data to third parties (including policing, DWP fraud investigation and for the purposes of the Hostile Environment) our opinion is that the rights of individuals to protections of rights and freedoms outweigh those of the Department, and distribution goes further than fair processing and parents’ reasonable expectations. The Reception Baseline Assessment, for national purposes, should not proceed.

- The Department for Education Data Management Review Group 2016 report with the aim of reducing teacher workload had a finding we can strongly support four years later. “Government, school leaders, and teachers, rather than starting with what is possible in collecting data, should challenge themselves on what data will be useful and for what purpose, and then collect the minimum amount of data required to help them evaluate how they are doing. Decisions about the identification, collection and management of data should be grounded in educational principles. In this way schools can have greater freedom to balance professional autonomy and agency against the demands of the accountability system.”[46]

- By contrast no work has been carried out from a child’s perspective or considering legal obligations towards data protection and privacy seen through the lens of children’s rights for the extensive research trials and innovation fund interventions. This should be done urgently through child rights’ impact assessment.

- The Core Content Framework for Initial Teacher Training[47] in England, which sets the parameters for a minimum entitlement in initial teacher education makes no reference to technology-supported learning, or digital rights, or data literacy skills despite the vast amount of assessment and accountability measures. This must change and become part of basic teacher training.

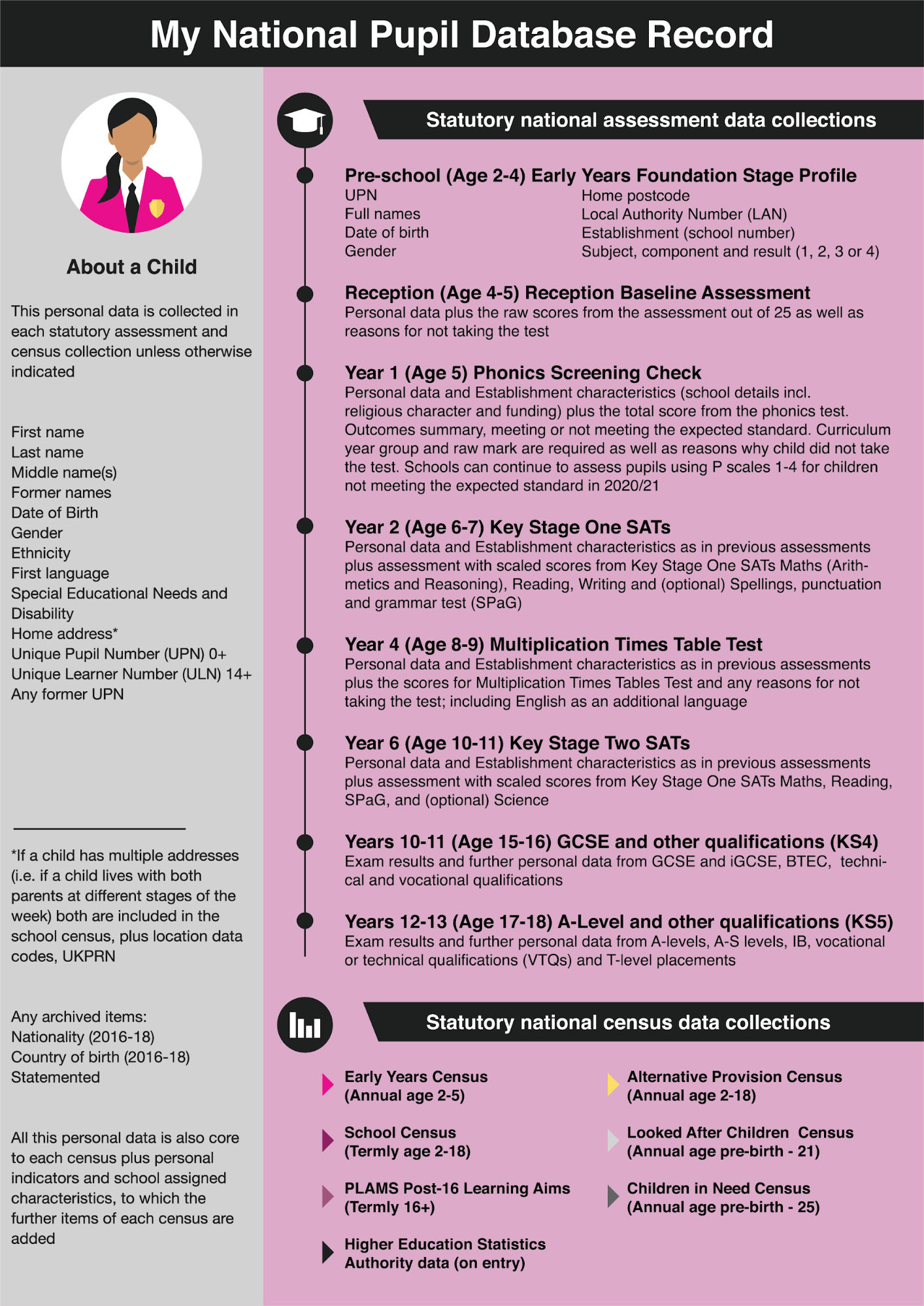

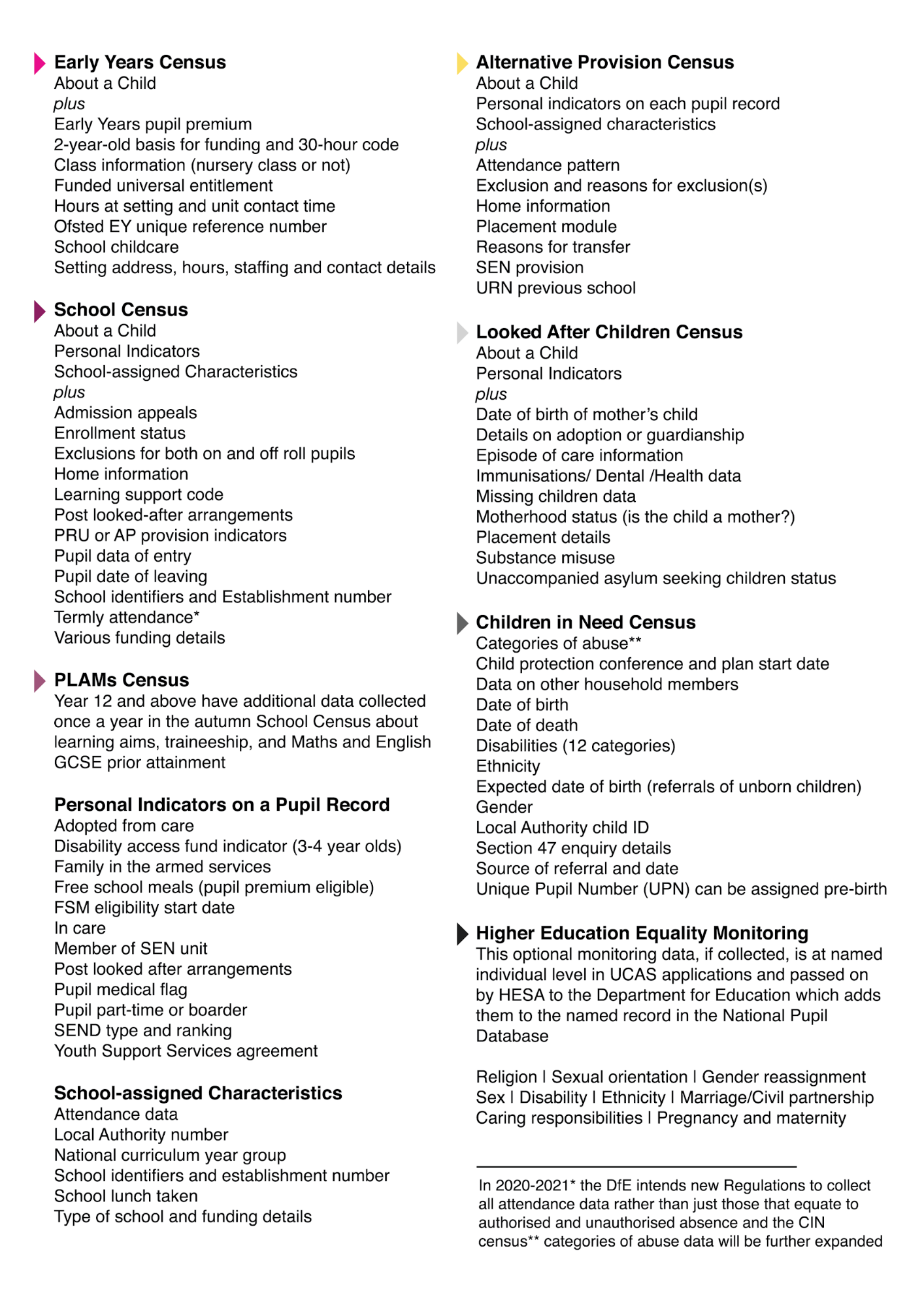

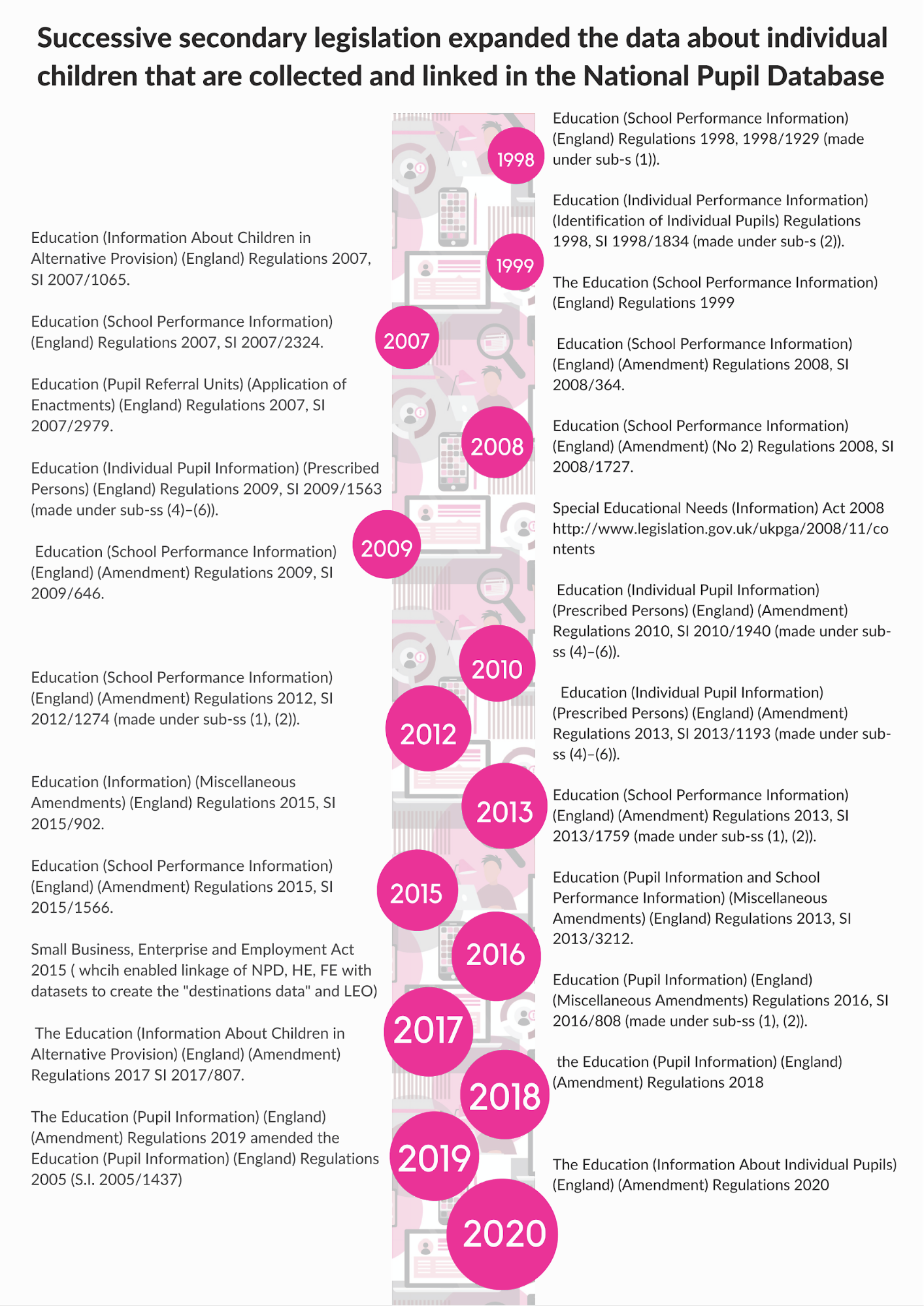

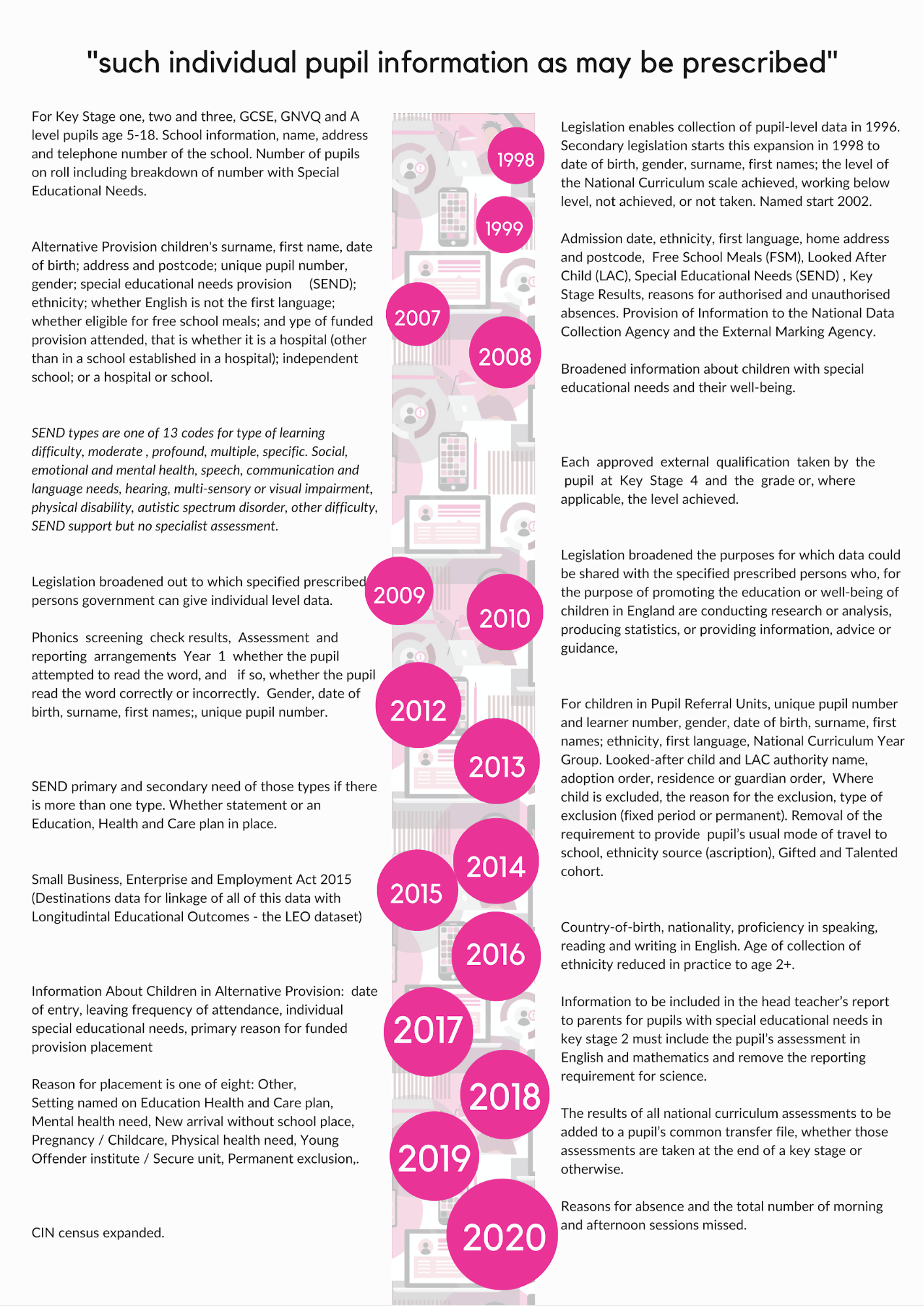

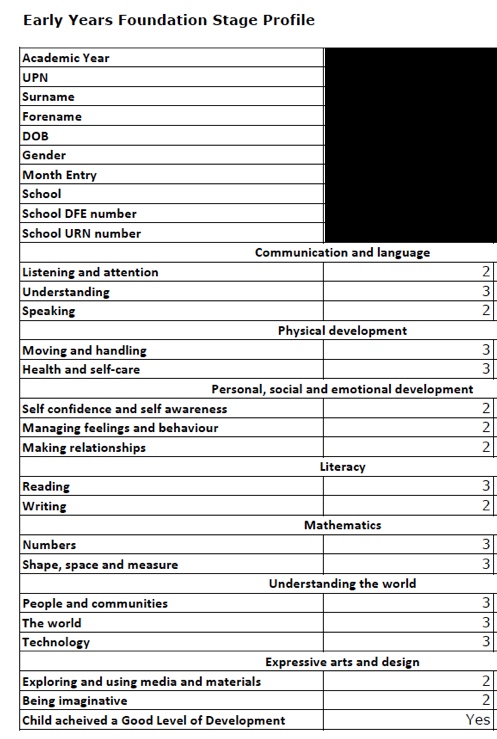

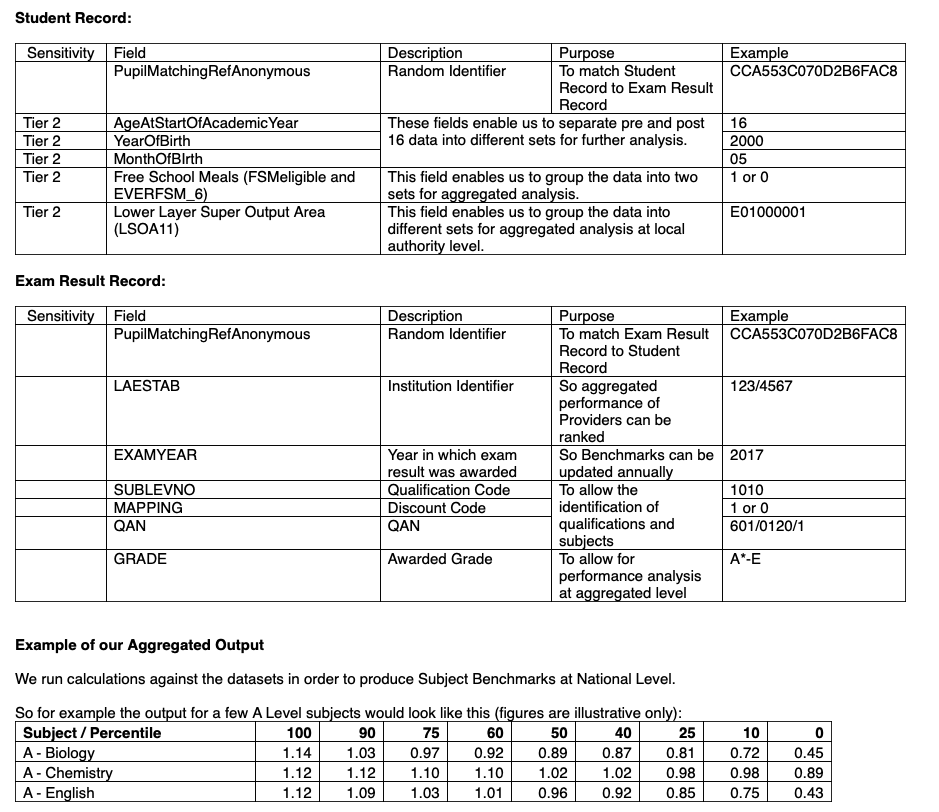

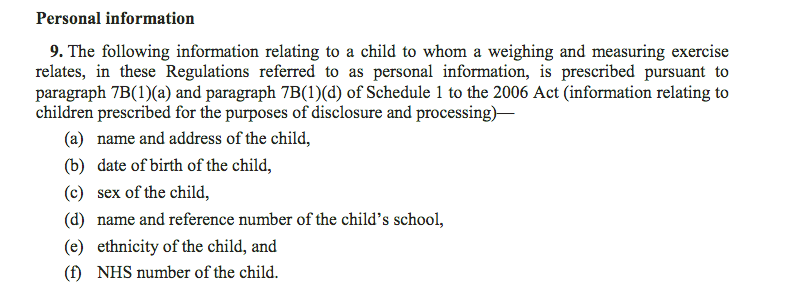

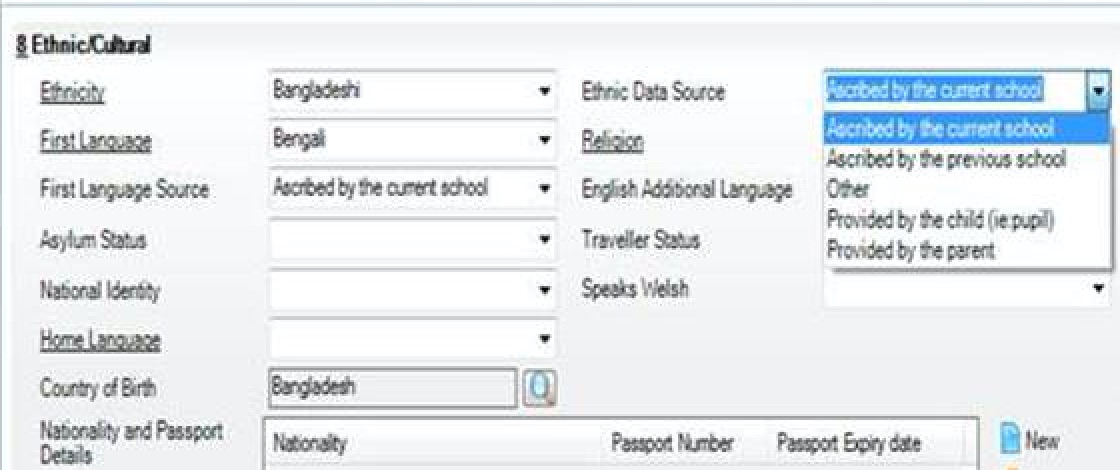

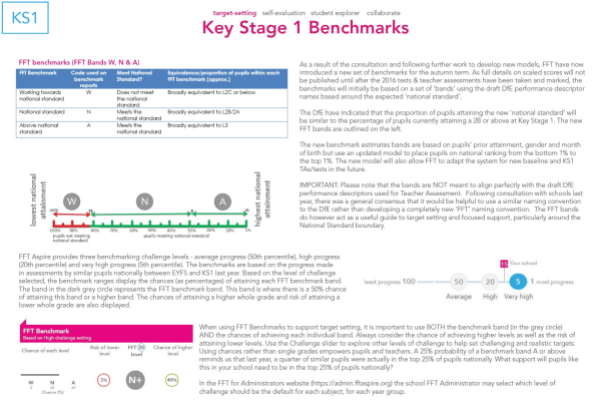

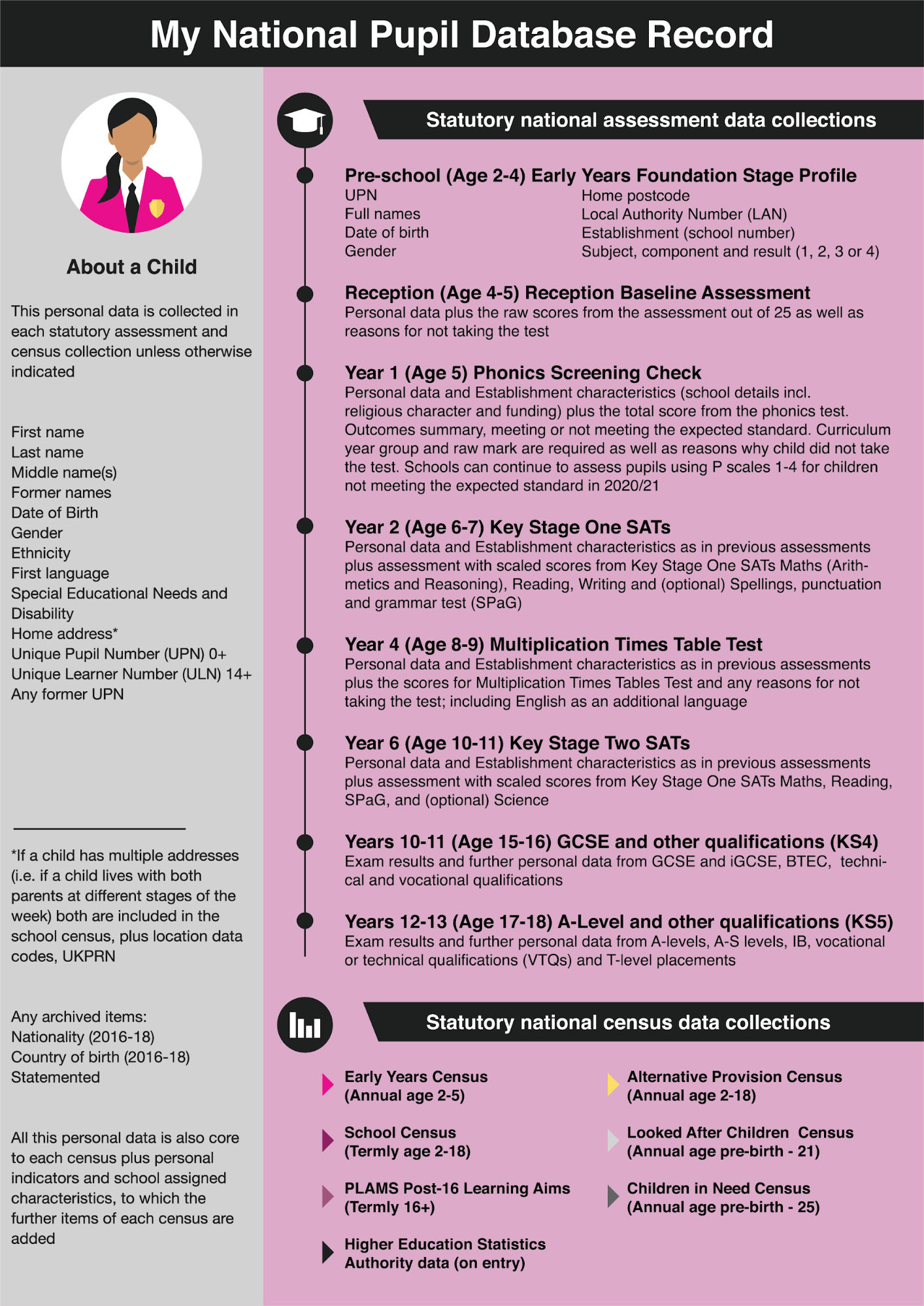

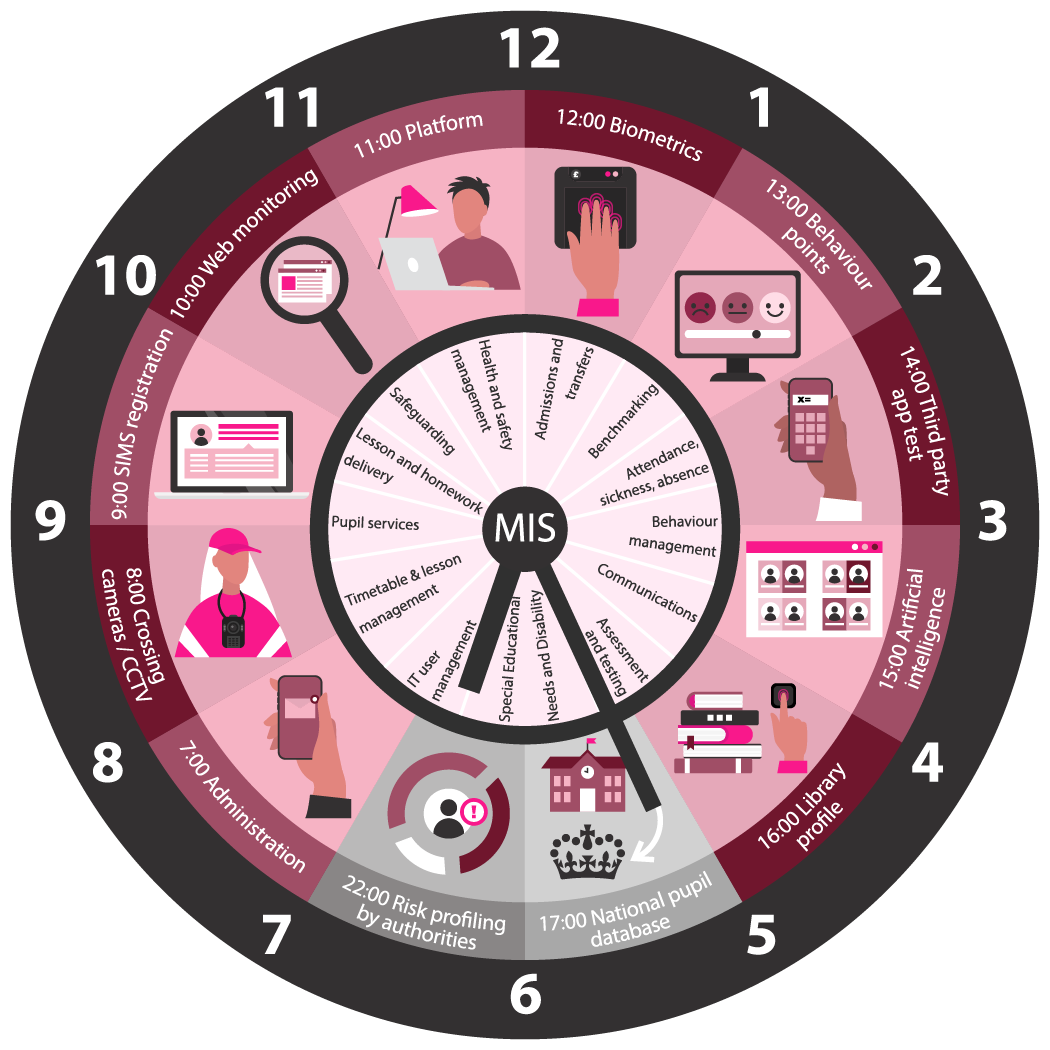

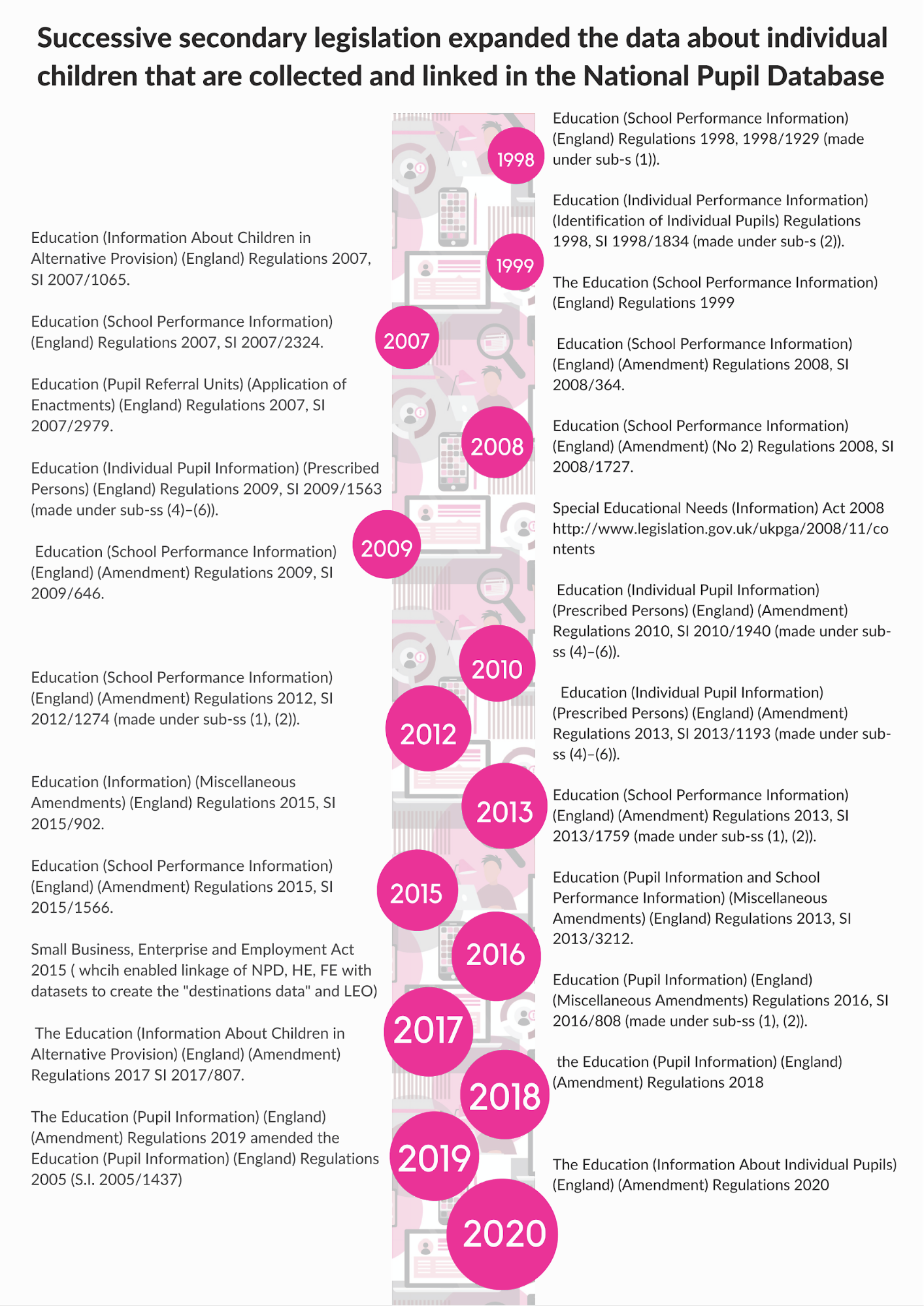

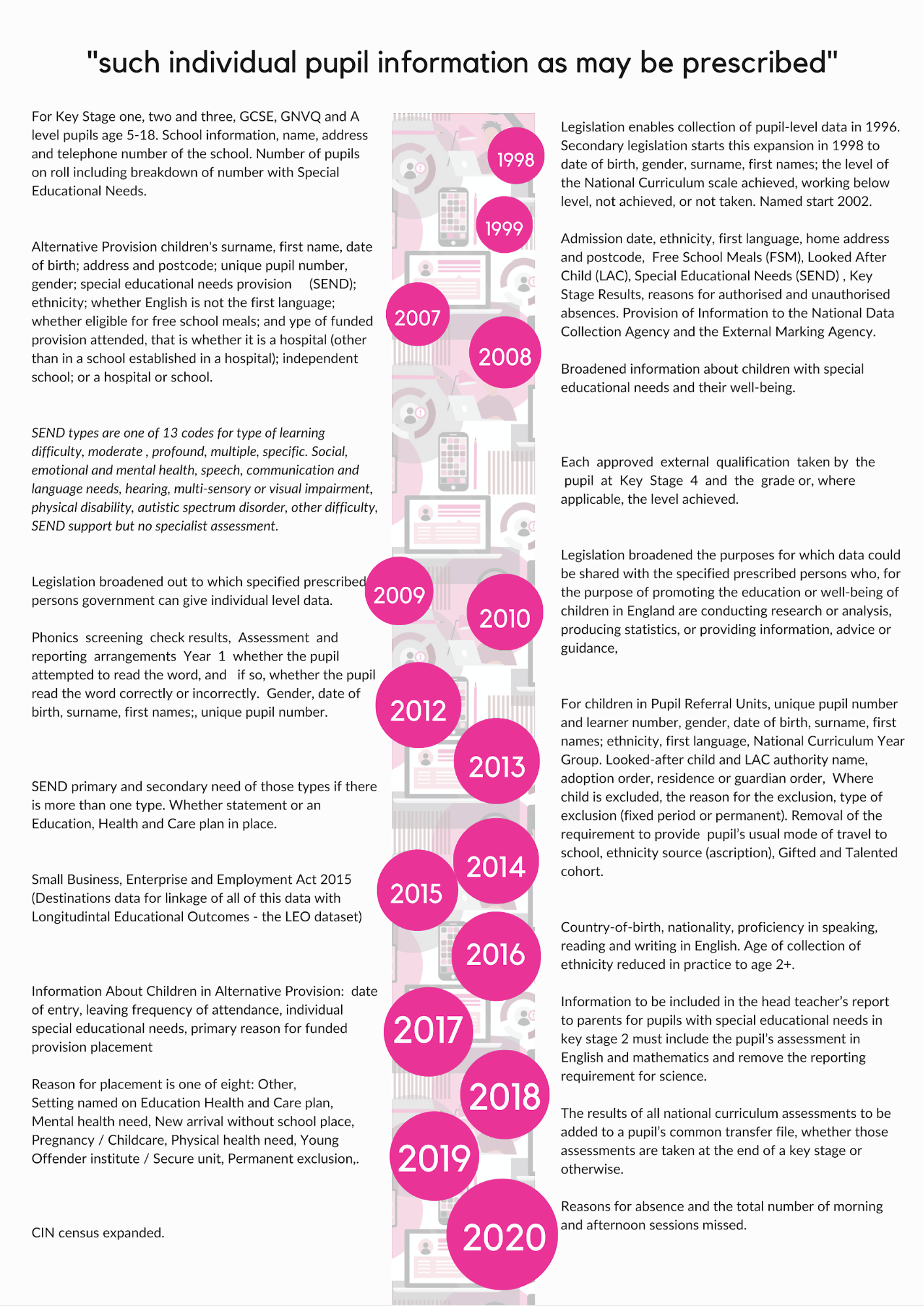

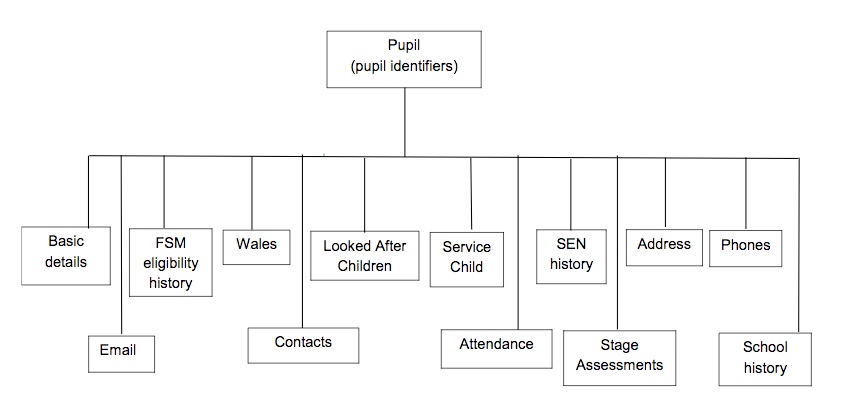

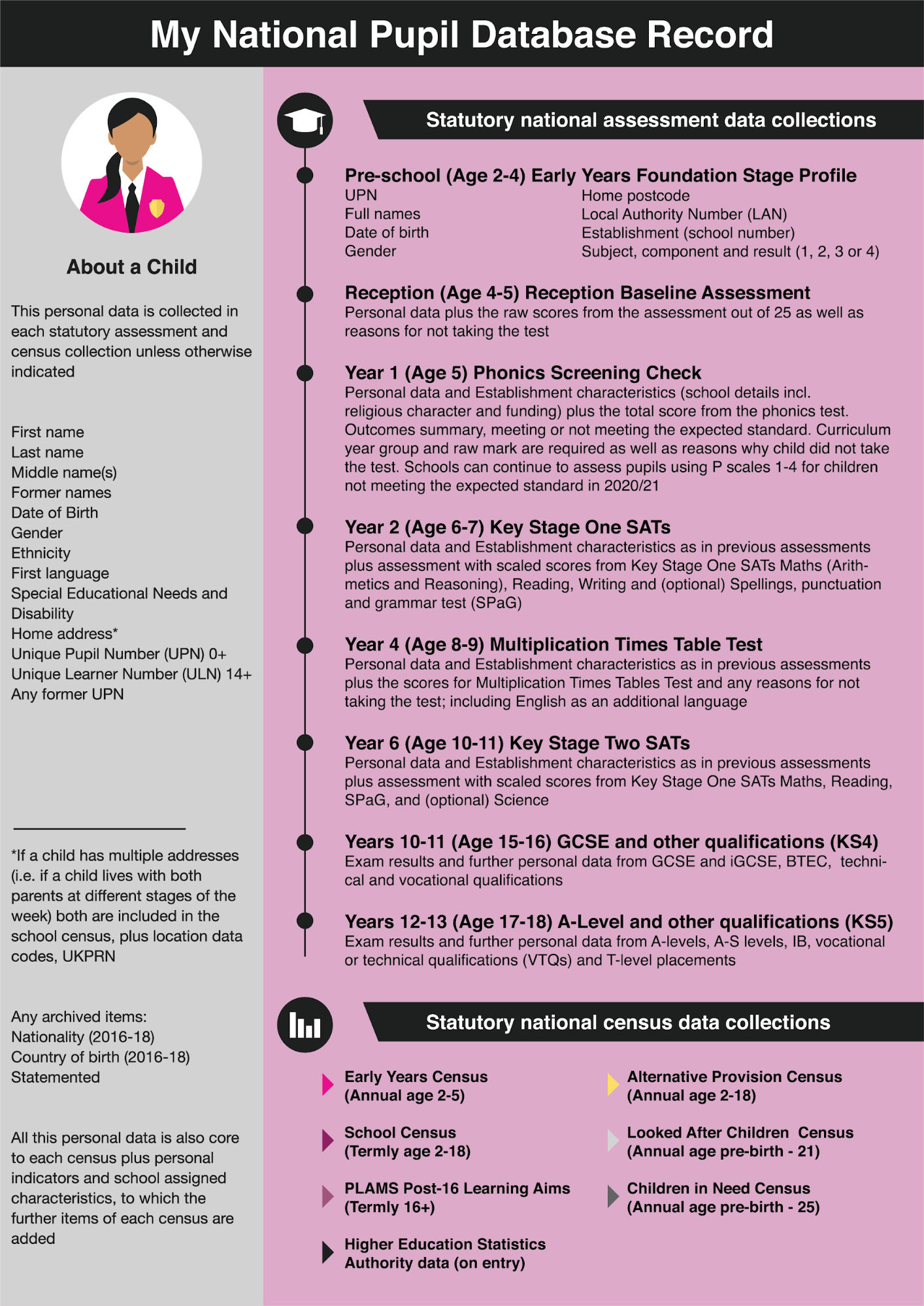

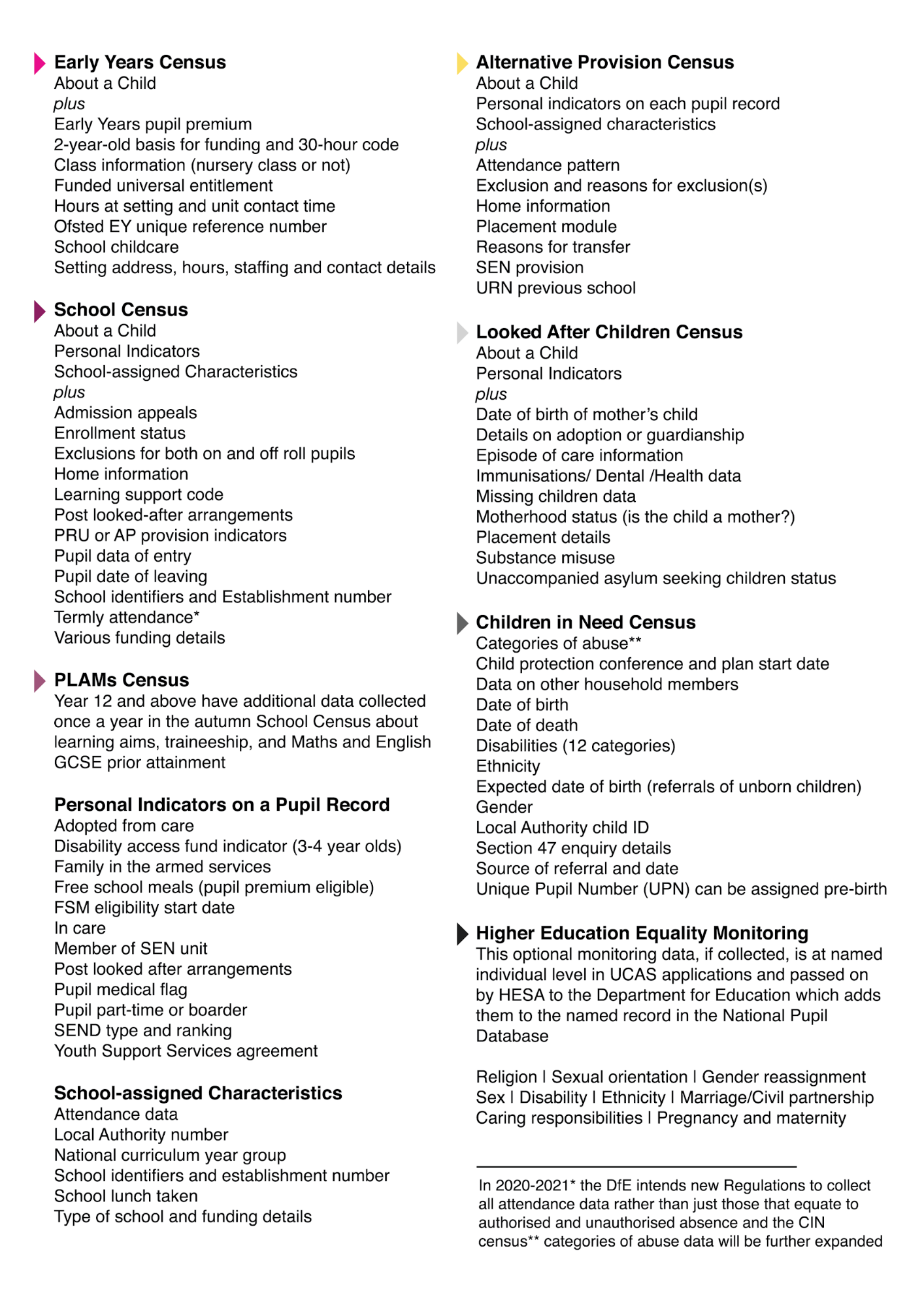

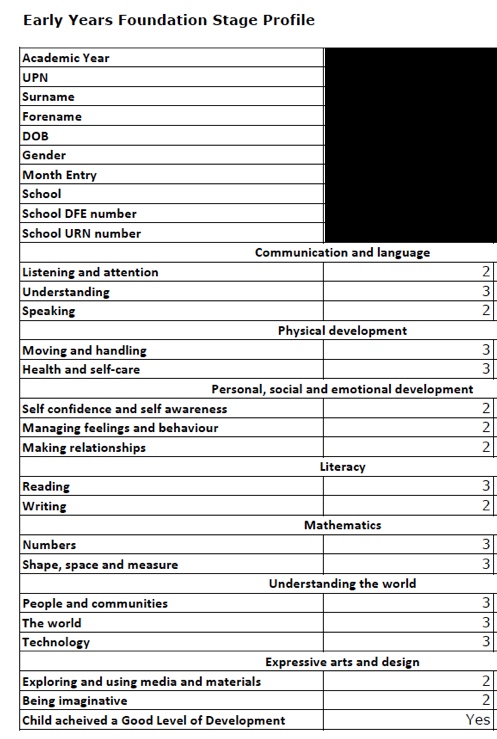

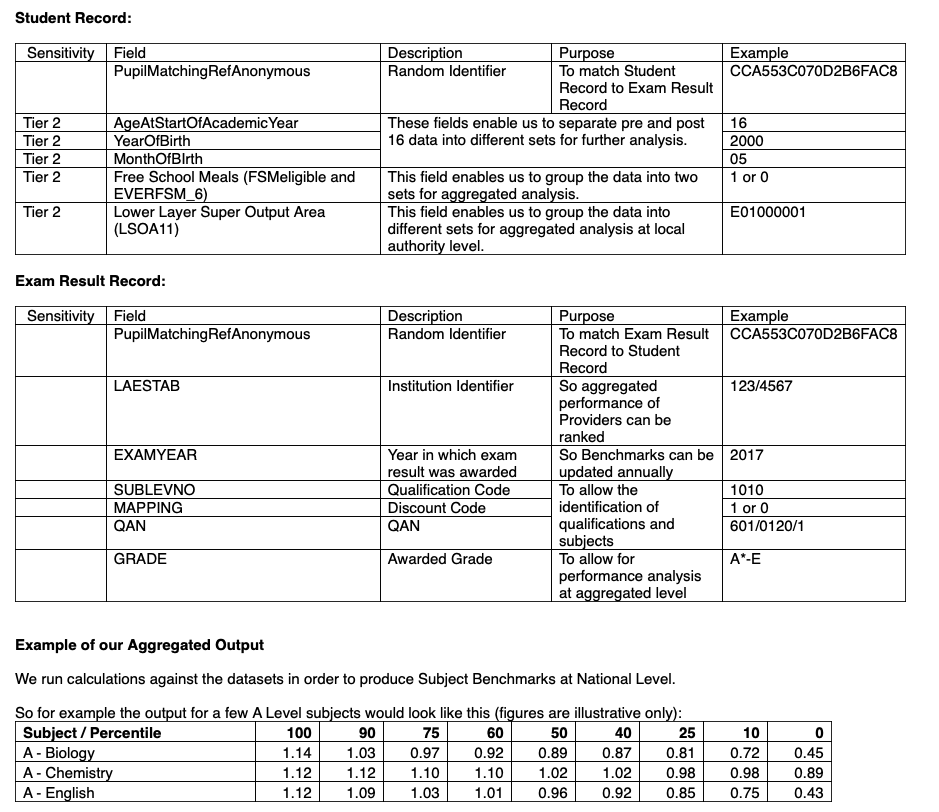

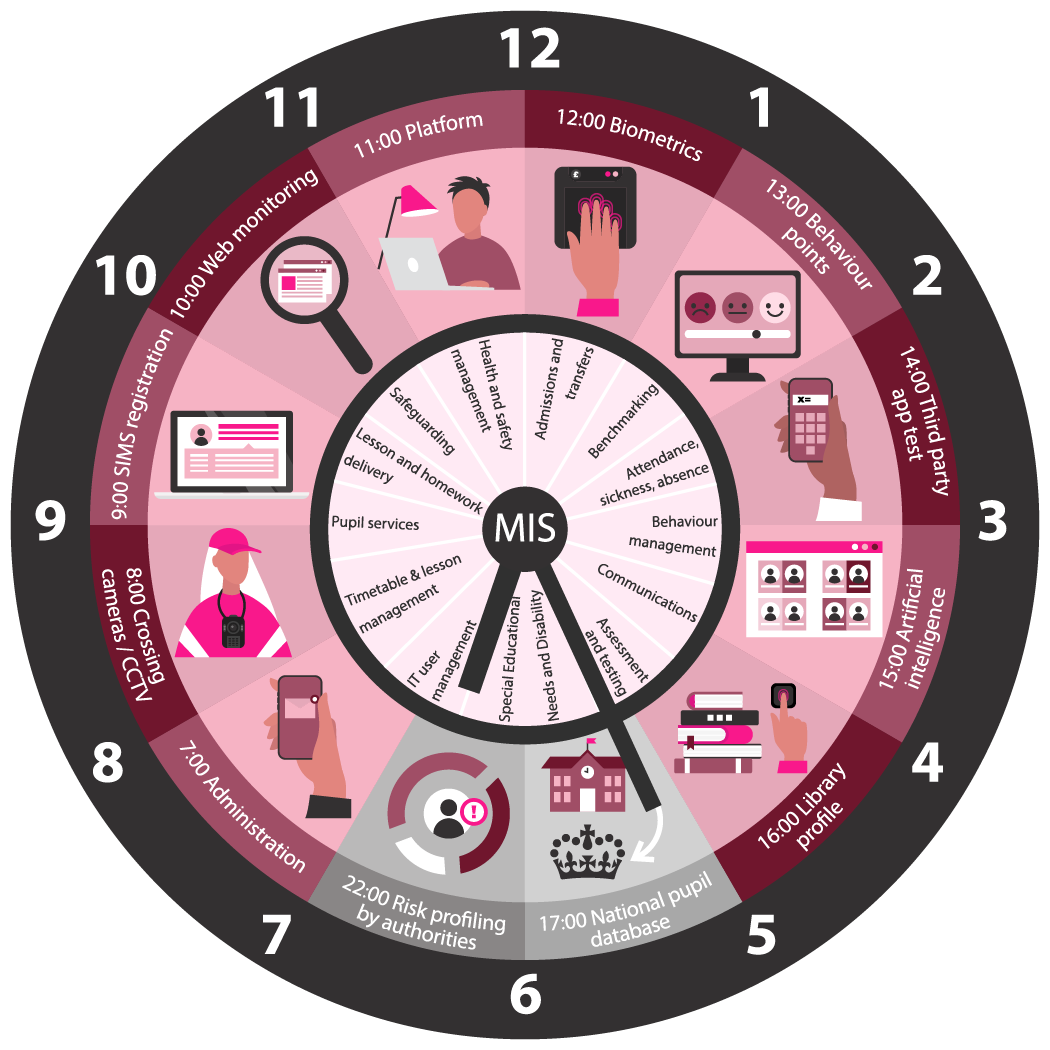

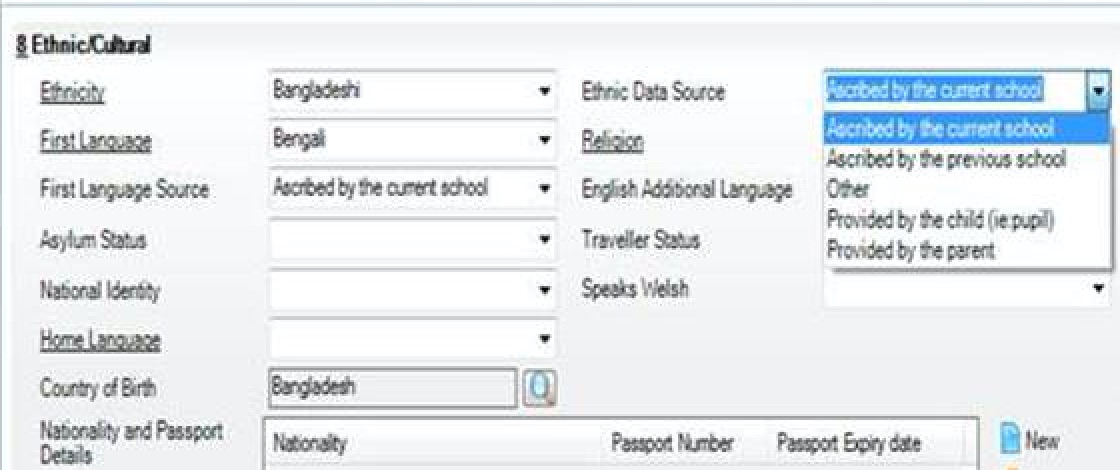

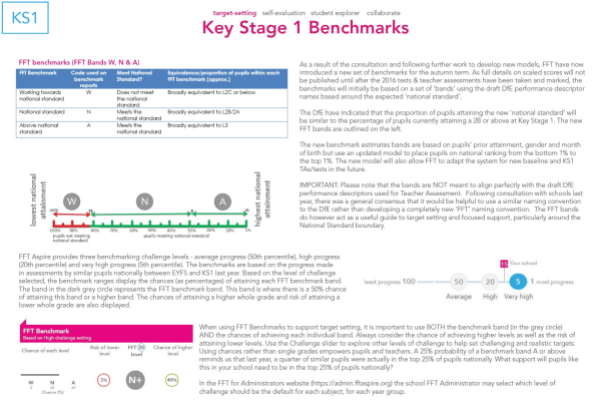

Fig.1 overleaf is an infographic to demonstrate the range of sources of data that may become part of a child’s national pupil database record in England, over the course of their lifetime education age 5-19. The records for a child that attends state funded Early Years educational settings will start earlier, any time from the rising 2s. A child at risk, may be captured in data from before birth if they are the child of a child, whose personal records will be sent to the Department for Education in the Children in Need (CIN) Census. Not every child will experience Alternative Provision or transition to Higher Education. But those who do, will have a larger named pupil record at national level. Personal data is sent to the Department for Education from every statutory test a child takes from the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile, to Phonics Tests, SATs and GCSE and A-Levels and more. The core data about a child are extracted in nearly every termly school census, annual census, and statutory test. Where this deviates is noted. Some items have multiple sub-categories of detail but we do not list them all in the chart, including SEND types that may be Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC), Speech, Language and Communication Needs (SLCN), Specific Learning Difficulties (SLD), Moderate Learning Difficulties (MLD), Social, Emotional and Mental Health Difficulties (SEMH), Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Sensory and/or Physical Difficulties.

We believe it is unnecessary and disproportionate for many of these details to be retained by the Department for Education indefinitely at named pupil level, and instead data could be extracted in anonymised, aggregated groups of data, or through statistical sampling.

NB. *Selected CIN data are not added to the NPD and some are restricted to Department for Education staff only.[48]

If you want to help us change this, please write to your MP and tell friends and family. You can see more information and steps to ask to see what is held in your own or your child’s record (since 1996) at: https://defenddigitalme.org/my-records-my-rights/

Fig 1 A National Pupil Database Record over a child’s lifetime

1.3.3.1 Recommendations Three | Admin data collections and national datasets Back to top

The ICO summary of its compulsory audit[49] of the Department for Education data handling is damning. Lack of oversight, accountability and lawfulness. National data collections of highly sensitive data have been rushed through successive parliaments in negative secondary legislation that far outstrip the data collection intentions of the original Education Act 1996 or squeezed into surprising places in non-education based legislation. Changes are needed in the making of legislation, risk assessment, re-use and repurposing of national pupil datasets, research access, and recognition of rights. Some national practice is currently unlawful, unsafe, and unaccountable. This needs substantial work to be fit and proper foundation on which to build a national data strategy “to drive the collective vision that will support the UK to build a world-leading data economy.” To be of greater value to users and reduce tangible and intangible costs to the state at national, local authority and school levels, national datasets should be reduced in size and increased in accuracy. The current direction of travel is ever more data and ‘mutant’ algorithms, when it should be towards more accurate and usable data within a trusted regime with standards, quality assurance and accountability. This needs action if the national data strategy is to become more than an aspiration

For Government at national level

- The Government should set out a roadmap towards a system of responsible education data including a governance framework and independent oversight by 2030, in a white paper for an Education and Digital Rights Act. Interim steps should be sooner.

- The government sets out its aim in the Digital Charter[50] to give people more control over their personal data through the Data Protection Act, and to protect children and vulnerable adults online. We suggest that this should start in education by recognising the need for change of its own practices at national level to protect children’s confidential personal data from use by third parties and for purposes far beyond our reasonable expectations.

- The Secretary of State for Education must act on the recommendation from the 2014 Science and Technology Committee Report Responsible Use of Data; “the Government has a clear responsibility to explain to the public how personal data is being used.[51]

For the Department for Education

- The Department must address all of the ICO findings in a timely manner and publish its changes to restore public and professional confidence in its data handling capabilities.

- Independent oversight should be established on a statutory footing for education data as a national data guardian responsible for national children’s data, and supporting educational settings with expertise in research ethics, algorithmic accountability and public engagement.

- Following its ICO audit and the national Learning Records Service breach[52] an independent audit should be carried out of the reuse of children’s personal confidential data from all national pupil datasets, distributed to third-parties, at national level.

- Introduce, improve and publish routine audit reports of third-party data distribution. The Department must be able to audit which child’s information was used in which third-party release and proactively provide this information as part of national Subject Access Requests