SATs and scores that last a lifetime

National Pupil Database pupil privacy / March 2, 2019

“These are not A Levels or GCSEs with results that count on an individual basis in the long term,” the Secretary of State for Education Damian Hinds wrote in the i, “SATs are not public exams – they are tests, and there is a difference.” We disagree these don’t count — here’s why.

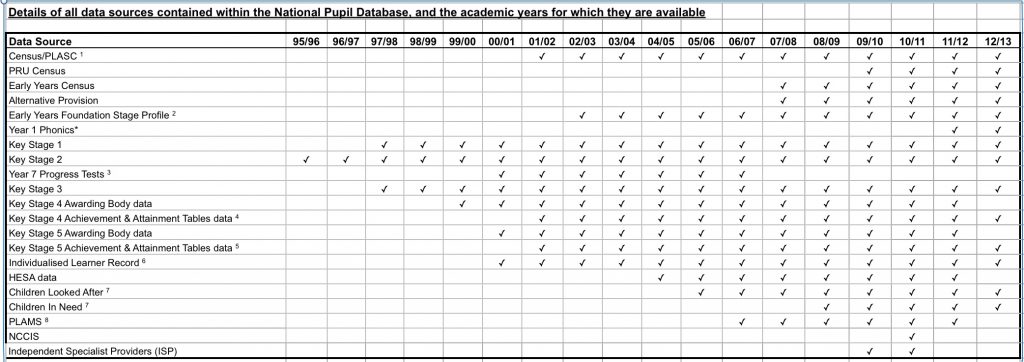

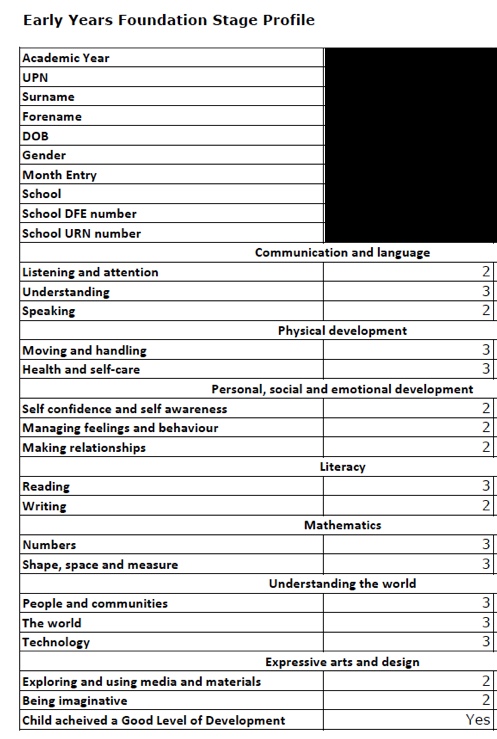

Every SAT score, together with every other state test and exam goes into the child’s lifetime record. That’s Early Years Foundation Stage age 2-4, Phonics at age 5, SATS at age 6 and 11, and later exams all sent for each child on a named basis, to the National Pupil Database. The National Pupil Database has over 23 million records, created from linking children’s personal details from the school census three times a year.

Test scores are stored up throughout a child’s life age 2-19, together with all their personal data — home address, date of birth, special educational needs, absence, Free School Meals, exclusions, indicators for armed forces families and children-in-care and more. Families are left completely in the dark, and its accuracy is never questioned. 69% in our commissioned survey last year, said they had not heard of the National Pupil Database. There is no meaningful communication to parents where children’s data go to from there.

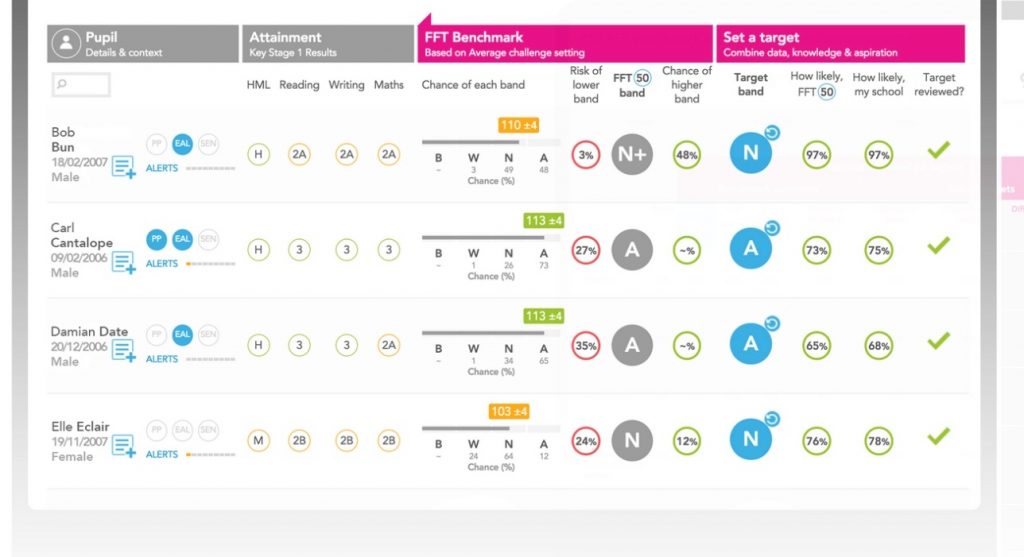

From there the Department for Education sends them to third party companies. The companies are sent the data for a range of purposes including reselling benchmarking data back to schools. The companies profile each child using the results. This is one example.

The profiles include risk scores — the company’s prediction of future academic performance, weighted for summer-born children and other factors — and the schools can then buy these processed data back again.

What each school gets back varies on which analytics company they use, but it can be vast and require a huge amount of interpretation. We are not the only ones asking, is the workload worth it? What is the real cost and benefit for a child, and for the school?

And this is all in addition to what the DfE offers schools directly. We know from anecdotal evidence, that some schools use profiles to target which selected handful of children will put the school at greatest chance of higher or lower school progress scores.

We’ve been told of schools that print the say, six children annually, whose risk scores, school believes could shift the Ofsted outcome, and whose score profiles are printed and pasted large to the staff room wall. The scores can influence if a child does or does not get more or less attention.

Teachers are under pressure to take scores into account when the outcomes have such high-stakes implications for the school, and for their own performance measurement, to greater or lesser extent depending on local decisions. We’ve been told by one primary Head, that although the school buys the results, she disregards them in planning for their 200 children, as she doubts their accuracy.

SATs can therefore enormously influence how a child is treated, consciously or subconsciously by school staff, and may overrule a teacher’s own views with no transparency of quality or accuracy — better or worse than the human judgement.

Prior attainment is fed into a lifetime records of scores, so mistakes in the data, or in what progress is inferred from the various results over time, might be built into records which are kept forever. With 8 million + children in school and 700,000 new each year, the chance of bad quality, or a bad day for a child, is high. And for every one, it means that each result and profile could have significant effect, for both a child and the progress measures which affect how a school’s performance is measured, and Progress 8 scores.

Increasingly, it’s not only schools or people in education and the national Department for Education that see these data. Or these national benchmarking companies.

SATs are being used as risk indicators not only of academic achievement, but across all aspects of everyday activity with the State across the wider public sector, and included in profiles that are used to judge whether or not to intervene in a child’s life.

SATs results are shared with third parties at regional level, and may be linked with an indefinite number of other datasets by local authorities and used to create these scores which families never see. Discrimination and error are then built-in for life across other public sector datasets, and could be based not on facts, but on best-guess opinions.

A Children’s and Young People’s Integrated Database has been built by joining together many databases including Phonics and SATs and Key Stage results in Kent for example, and even includes ‘Mosaic’ data bought from consumer Data Brokers Experian. That’s not how parents expect their child’s personal data will be used when they send their child to school. We don’t expect authorities to link it with other data we’ve never seen. We hand over data for their schooling. For anything more, we should know.

But all of this data transfer, the profiling, and any effect is often hidden to families.

These mega databases using school children’s records, are growing without oversight. A recent study by the Cardiff Data Justice Lab, explored the Bristol Data Analytics Hub which holds the data of 54,000 families — without their knowledge or clear necessary and proportionate reason balanced against risk — and was mentioned by SkyNews in this film.

Some of these uses for linked datasets now go far, far beyond what parents would find reasonable. In Bristol today, every child in school may not know that their school records are being sent to a local Integrated Dataset. Not children who are known by the authority to be at risk of harm, but the personal records of *every single child* in school. Data is transferred daily overnight. But who tells the children or their parents?

We believe this kind of privacy notice, like the way Local Authorities say they tell families how data are used, completely fails, and it matters.

Enormously significant decisions are made using these kinds of risk databases, ranking every child with a risk score, and using automated decisions to rate everyone — without any way of separating between facts and opinions, or in the case of the London Met Police Gangs Matrix, any way to separate between victims and criminals.

Still think these SATs scores, “don’t count”?

SATs not only count, but may count badly against you. Performing poorly at school may be a result of factors connected with poverty, but in any risk averse system, bias means the system may not be set up fairly in favour of your rights and freedoms to live your life without interference.

Risk factors [particularly if they have a shared root cause] can reinforce the others, re-affirming a perceived increased level of risk. And if you tick enough boxes (two for ‘Troubled Families’ in the latest presentation we saw) you get ear-marked for intervention. These interferences in family life can have lifelong effects, and rather than solving structural social problems, tend to reinforce them. SATs scores used in this way are very likely to contribute to holding back, not improving, social mobility, and restrict a child’s right to a full and free development and the freedom to flourish.

There is good reason why the General Data Protection Act includes that profiling with significant decisions, should not routinely apply to a child. These systems don’t have the sensitivity or humanity, that children’s care demands.

Our Right to Know, and Right to Object to uses where it applies in routine data sharing, must be respected by the State. Every child must be informed how and where information about them from school are used, and there should be no surprises. Re-use of school records without fairly telling families must end. Risk profiling children should end. Instead of the current one-way mirror, — where all our information goes to the State and no information comes back to us how it is used, — we should be getting reports that explain it. Registers should transparently record every user. And we must be able to have Subject Access Requests respected, because with all this third party use and no ability to have errors corrected, our Right to Redress when things go wrong is nearly impossible.

We strongly disagree SATs don’t count.

In fact, Damian Hinds probably doesn’t know how much they are used and shared with third parties, and that probably reflects exactly how little the average parent knows. Probably no one really knows how much these data are being passed around as local registers have still not been set up — and families are not informed about where their data go from the national database. If we parents don’t know, how on earth can we expect our children to be empowered digital citizens, understanding Who Knows What About Me.

If you are under 36, or have children in state education, you might want to find out what the Department for Education holds about you or your child. We have set out a step-by-step guide to help you. You’ll need to ask online, and only when asked to do so, provide some proof of identity and relationship to any child on whose behalf you are making the request.