Statement on appointment of the Reviewer for the Prevent programme

Prevent pupil privacy safeguarding / August 19, 2019

“An incredibly broad range of people and organisations have raised concerns about the impact of the Prevent strategy, including politicians of all parties, health and education workers.”

On August 10th, we signed a letter, among a wide ranging coalition of human rights organisations, including Index on Censorship, Liberty, and Runnymede Trust, to warn government that the required review of Prevent, as part of the Home Office counter-extremism strategy, risks becoming ‘whitewash’. We then shared objections on the process to date, and the appointment of Lord Carlile to lead it, which undermines its credibility, as set out in yesterday’s Observer.

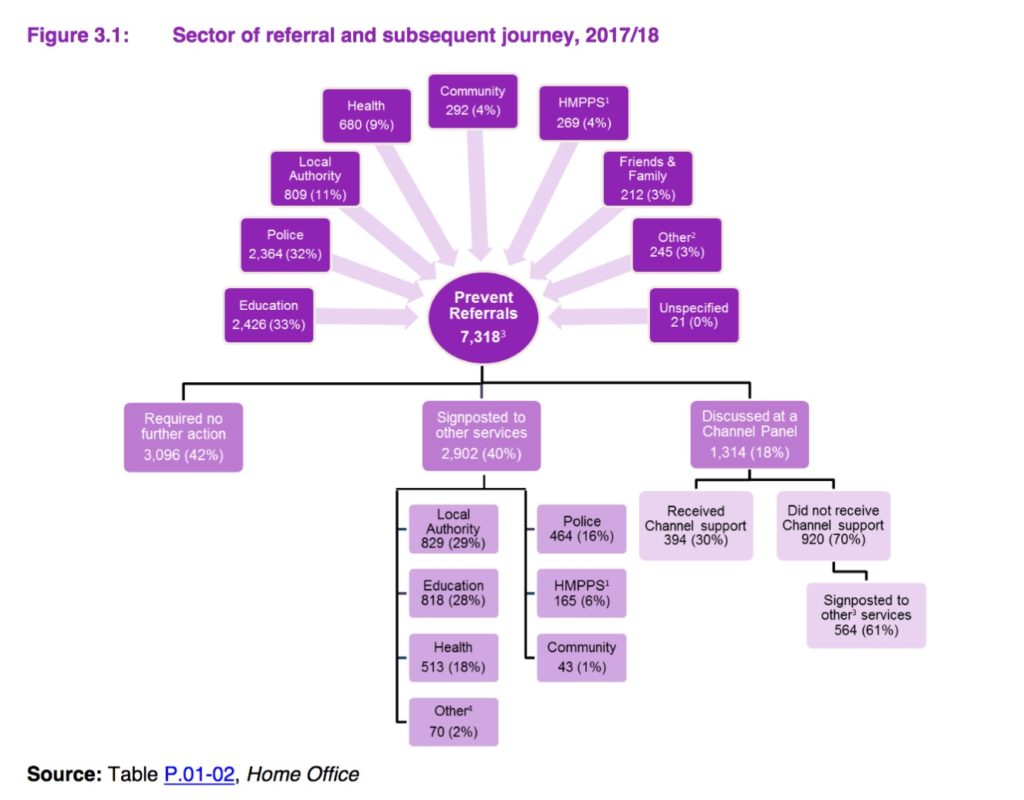

The education sector made the most referrals (2,426) to the Prevent programme in 2017/2018, accounting for 33%.

In 2017/18, of 7,318 individuals referred, the majority (4,144; 57%) were aged 20 years or under. Those aged 20 years or under also made up the majority of the 1,314 individuals discussed at a Channel panel (818; 62%) and 394 individuals that received Channel support (259; 66%)

[Source: Home Office statistical bulletin December 2018.]

The review must examine Prevent’s “underlying assumptions and evidence base, its human rights implications, and, ultimately, whether it is fit for purpose”.

We are often made aware of aspects that negatively affect children and need to change in particular in relation to Internet monitoring software that can contribute to children’s profile building behind the scenes. The scope of these software have expanded since the introduction in 2015 of safeguarding in schools statutory guidance by the Department for Education. Children have been wrongly labelled as potential gang members or as at risk of suicide, there are secret data stashes about them held in the UK and abroad, and some enable the webcam to be used to take photos of a child without their knowledge. That is not what parents expect when their child ICT agreement says, we understand Internet use will be monitored and policies don’t make purposes of the data collections at all clear. We need safe, transparent, clear and consistent, rights-respecting policy and practice in and beyond schools, where these tools operate through the state education sector but can reach into children’s private and family life.

In 2018-19 we asked only six Local Authorities’ multi agency safeguarding boards for information around referrals from schools. We hit a wall of refusals to be open, and could not make progress since children’s safeguarding boards are not subject to FOI law. There is no transparent scrutiny or oversight process around the children’s records and outcomes.

The Review must address these processes and bring about real change having recognised its failings and need for improvement. But we are concerned that the Review will not be objective and there is no serious intent in government to listen to its failings or design for change.

In June, the government assured Parliament and the Joint Committee on Human Rights that the appointments process would follow the Cabinet Office Governance Code on Public Appointments. Yet the government failed to follow that Code, including failing to publicly advertise the position or publish information about the selection criteria.

The Prevent Oversight Board, of which Lord Carlile is a member, has met only 7 times since 2012, most recently in November 2018 and in December in debate [House of Lords (17 December 2018) Hansard], the Lord said he felt it unfair to criticise the Prevent strategy. Charged with driving delivery of Prevent, Lord Carlile has given it his “considered and strong support” as he called it, in the 2011 preface of his last Review.

And despite finding no evidence of radicalisation at that time, saying, ‘Schools are important not because there is significant evidence to suggest children are being radicalised – there is not…’ in the debate in December 2018, opposing more transparency reporting, he suggested that the Prevent programme, “does achieve considerable success in finding those young people who are being radicalised, often in private, in their rooms, over the internet” — so we wonder if he is aware of or willing at all to listen to its unintended consequences and effects for children on their human rights. We hope so.

However, there seems to be little hope for independence in a Review whose framing appears set from the start. We start this process deeply disappointed that it seems nothing more than a tick box, and its intent is disingenuous. Whether or not we engage further, will depend on the government’s response and the Terms of Reference expected soon.