Data Protection Day 2020

pupil privacy / January 28, 2020

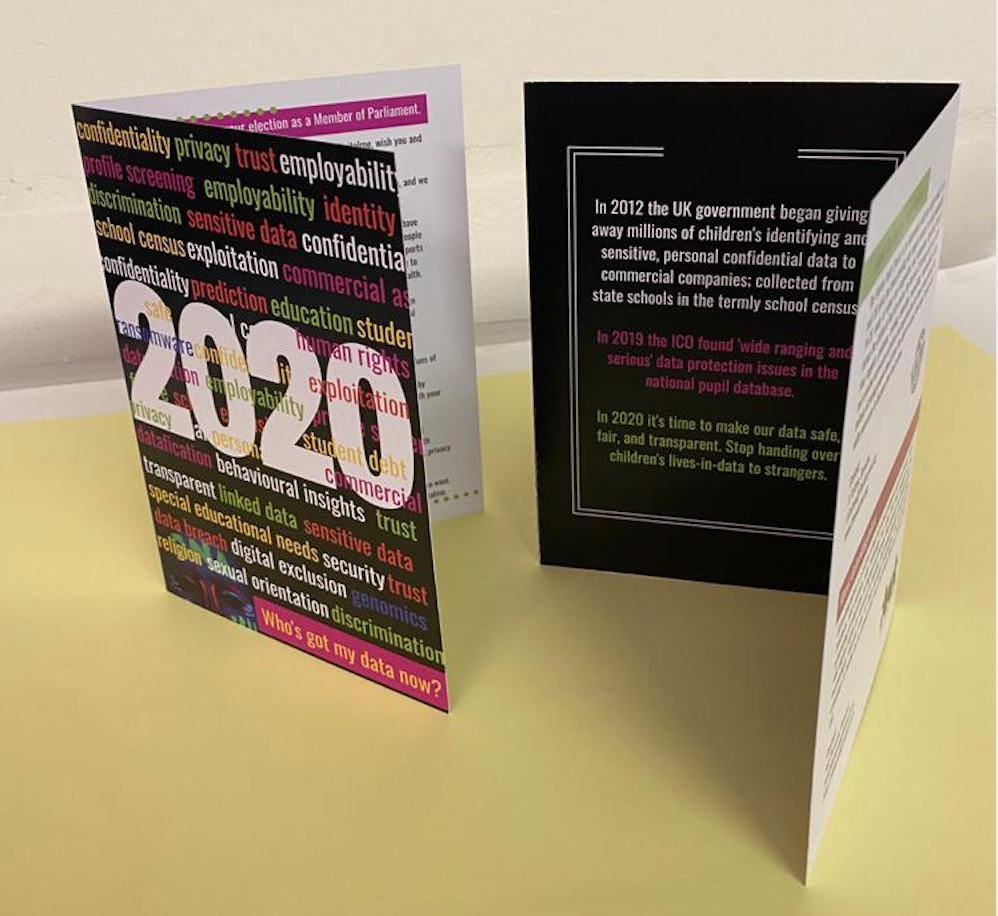

Today, on Data Protection Day 2020, we have written to every MP to call on the government to give back control of school children’s personal confidential data to families.

We are also calling for an independent enquiry on national pupil data processing.

Families don’t know where our data go or why

The DfE provides schools with privacy notices, which include details of the National Pupil Database (NPD) and its uses by thousands of third parties.

But attempts at self-improvement have failed to date to bring sufficient change. Such notices never reach families, are not suitable for children, and don’t work.

The data protection regulator, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), wrote to us in October 2019, that as part of their regulatory work into complaints we had made against the DfE national pupil data processing, they found wide ranging and serious data protection issues. For example, that the privacy notice fails to meet the DfE lawful obligations of informing families how their children’s data are used, and their rights.

“This investigation has demonstrated that many parents and pupils are either entirely unaware of the school census and the inclusion of that information in the NPD, or are not aware of the nuances within the data collection, such as which data is compulsory and which is optional. This has raised concerns about the adequacy DfE’s privacy notices and their accountability for the provision of such information to individuals regarding the processing of personal data for which they are ultimately data controllers. “

That backed our findings from our 2018 parents’ survey, and a very new YouGov poll commissioned by MoreThanA Score. The findings include, only 4% of parents surveyed are aware of the extent of government testing in primary schools. Families and pupils don’t know national pupil databases exist, or where test scores go, let alone have any control over how it is used.

Producers of official statistics must commit to detailed practices, which includes thorough communications, for organisations to be worthy of trust. But that is now in short supply.

In the last three years, we’ve discovered a national data collection that was introduced for the Home Office not to benefit children or the purposes of education, while schools and families were misled. Few knew until July this year, that sexual orientation and religion is added to students’ named records and kept by the Department. Now we discover uses by identity check and screening companies. What else might be hidden?

Misuse of millions of people’s personal data demands an independent enquiry

The recent misuse of the Learning Records Service by an approved LRS user, passing on access to an identity check company, was unauthorised and not sanctioned by the Department, say Ministers.

While the LRS is separate from the National Pupil Database, it reveals further significant gaps in the conduct of the Department’s governance and oversight.

The Times reported that Gavin Williamson, has ordered his department to “leave no stone unturned” in ‘strident action’ its investigation. We support the call from the former Chair of the DCMS committee, Damien Collins for an enquiry. But it cannot be internal. An independent and system-wide audit is required of this and all education datasets; collection, distribution, access and processing; all need reviewed as done in 2014 in the NHS to ensure no more surprises.

Let’s not be distracted by the bad actors, either.

Giving away pupils’ personal confidential and identifying data at the Department to third parties is routine, not accidental.

The government changed the law in 2012 to create a market for our children’s personal confidential records. In addition to today’s 8 million school children, there are over 20 million people in these DfE databases, who are no longer in school. While the Department may appear to think it is satisfactory, to ignore those people too, it is not. People must understand which data are collected and where they go and why, and have their rights to object, among others, explained. It is a data protection law obligation.

No one expects our school records to be given to private tutoring companies, charities, consultants, think tanks, data intermediaries, or journalists. Or to join up with police data or for classroom interventions. We have the right to object. We should be able to decide if and which third parties our data are shared with for purposes beyond our own education.

There are rights to object and request restriction of processing that the Department fails to explain.

They must stop giving away our children’s lives-in-data to strangers.

On 26 April 2006, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe decided to launch a Data Protection Day, to be celebrated each year on 28 January.

It is the anniversary of the opening for signature of the Council of Europe’s Convention 108 for the Protection of individuals with regard to automatic processing of personal data. It is a cornerstone of data protection, for over 47 signatories, in Europe and beyond for over 30 years. This year it will publish recommendations for children’s data protection in education. But our government must not wait to get this right.

“The aim of the Data Protection Day is to give individuals everywhere the chance to understand what personal data is collected and processed about them and why, and what their rights are with respect to this processing.“

“They should also be made aware of the risks inherent and associated with the illegal mishandling and unfair processing of their personal data.“

Our national pupil databases have been around for over 20 years and grow by over a million every year. If Ministers will not tell us all, what the government is doing with our personal data today, and give us control over it, then when?

We have written to every MP asking for their support.

Background: The National Pupil Database

Confidential personal data are given away

Children’s names and personal details including home address, Date of Birth, Special Educational Needs, gender, ethnicity, reasons for exclusion, on behaviours and moves, service and looked-after-children indicators, pupil premium, are all sent to the Department for Education.

From there the personal confidential and often named data are widely distributed despite new processes that were introduced by the Department after GDPR came into force in 2018 intending to end the data distribution.

Last year, then Secretary of State for Education Damian Hinds wrote about SATs tests, in the i, “These are not A Levels or GCSEs with results that count on an individual basis in the long term.”

We disagree. The distribution of these tests as part of children’s records in large volumes can have long term hidden effects on children. The Department for Education has given away identifying and sensitive data from millions of children to companies for benchmarking and reselling data back to schools, or to charities, and other researchers. Local Authorities pass it on to commercial companies for risk scoring every child for future achievement, link it with children’s health data and even rate families for predictive risks of child abuse without understanding its flaws, data never designed to be measures of a child but for the school accountability system. Some local authorities now even link it with more detailed data bought from commercial data brokers.

Changing the law in 2012, DfE chose not to tell everyone affected, and processing is unfair

The National Pupil Database, just one of the DfE’s fifty databases, began in 1996, named since 2002, and now has over 23 million records. It is created by taking out children’s personal details from state schools for children aged 2-19, three times a year in the School Census, and linking it with statutory test scores, Key Stage SATs tests, together with exam data goes into the child’s lifetime record. That’s Early Years Foundation Stage age 4, Phonics at age 5, SATS at age 6 and 11, and all later exams all sent for each child on a named basis, to the National Pupil Database and are kept forever. The Baseline Test and Multiplications Times Tables Check will soon be added too.

Later in life, further data extractions are added, such as Higher Education equality monitoring from university applications. And it is being later linked with earnings and welfare records without the public’s or policy makers’ understanding of its implications.