Towards the UK Education and Digital Rights Act

National Pupil Database / February 10, 2020

February 11, 2020: On #SaferInternetDay 2020 today, we are somewhat frustrated at the regulator’s lack of enforcement on serious breaches of privacy and data protection in UK schools. But data protection regulation, even with enforcement, will not be enough to build a rights’ respecting environment in education. Here’s what should change.

Given national data uses that go beyond reasonable expectations are in the news yet again, we are summarising our proposals here, for safe national pupil data, and reform.

Policy makers have a duty to respect, protect and fulfil the rights of the child in the digital environment. Children shall not be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with their privacy in the digital environment. How do we make it happen?

In paragraph 8 of its general comment No. 1, on the aims of education, the UN Convention Committee on the Rights of the Child stated in 2001:

“Children do not lose their human rights by virtue of passing through the school gates. Thus, for example, education must be provided in a way that respects the inherent dignity of the child and enables the child to express his or her views freely in accordance with article 12, para (1), and to participate in school life.”

Those rights currently unfairly compete with commercial interests. The State ignores them. Data protection law alone, is weak protection for children in compulsory education.

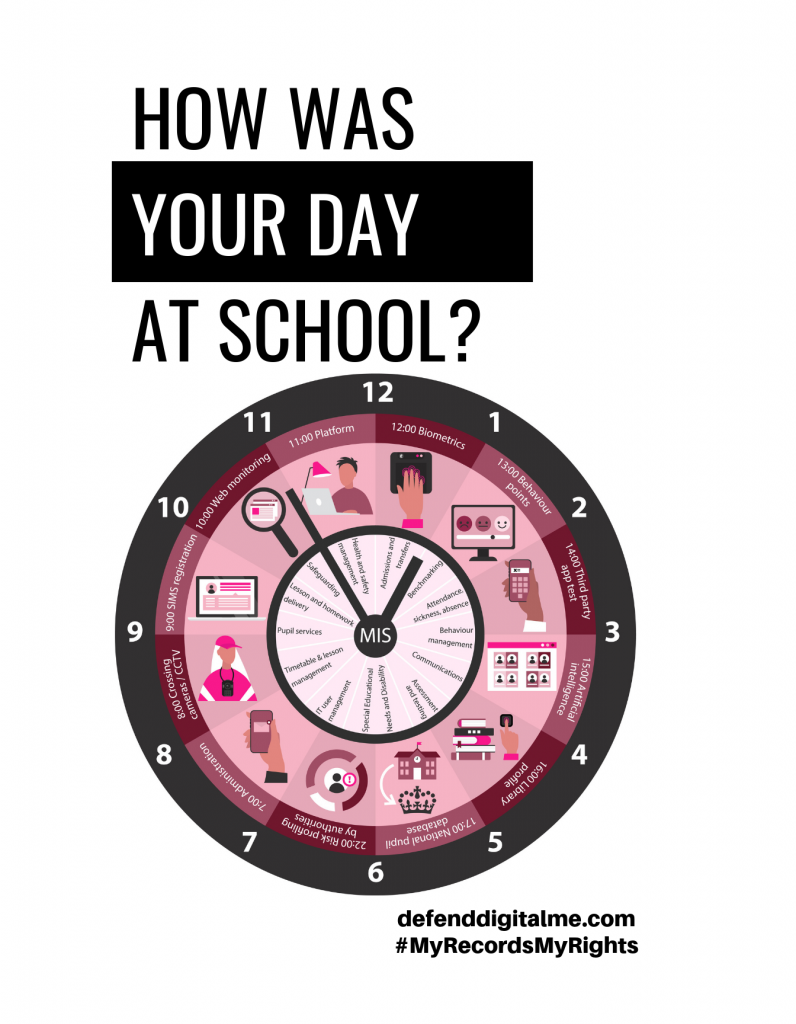

In addition, there are serious risks and implications for the system, schools and families due to the routine dependence on key technologies at national, local authority and local levels:

- National infrastructure dependence ie on Google for Education ‘freeware’

- Tangible and intangible risks of interaction and interventions through 1000s of third-parties at school level without quality and safety standards, or oversight

- Data distribution at scale, and dependence on third-party intermediaries

- Re-use and linkage of pupil data at scale in predictive modelling, often coupled with austerity, and the search for easy solutions to complex social problems.

The rapid expansion of educational technology without national transparency, accountability, and oversight, has meant thousands of companies control millions of children’s entire school records. Companies go on to be bought out and ownership can be transferred in foreign takeovers multiple times in the course of a child’s education or lifetime. The child and family will never be told their personal data are controlled by another company. The school may be forced to accept new terms and conditions without any choice or face losing core system software overnight. There is no way that a child can understand how large their digital footprint has become or how far it is distributed to thousands of third parties across the education landscape, and throughout their lifetime.

Local Authorities commonly reuse data for linkage and non-educational purposes.

At national level, our research shows that school staff, children and parents in England don’t know the National Pupil Database exists, despite it holding the personal confidential records over 8.2 children in school today, among the growing total of 21+ million named individuals.

The ICO agreed (Oct 2019) after initial investigation of school census use, that:

“many parents and pupils are either entirely unaware of the school census and the inclusion of that information in the National Pupil Database or are not aware of the nuances within the data collection, such as which data is compulsory and which is optional.”

Public authorities need to establish an improved default position of involving parents in decisions before sharing their children’s personal data, unless a competent child refuses such involvement or where sharing poses a risk to the child’s direct best interests.

Consent, contract and confidentiality

The investigative burden in schools at the moment is too great to be able to understand some products, do adequate risk assessment, retrieve the information required to provide to the data subjects, and be able to meet and uphold users’ rights. School staff often accept using a product without understanding its full functionality.

The Joint Committee on Human Rights report, The Right to Privacy (Article 8) and the Digital Revolution, calls for robust regulation to govern how personal data is used and stringent enforcement of the rules.“The consent model is broken” was among its key conclusions. Consent does not work for education for routine data processing under Art. 6, due to the power imbalance.

Contract cannot work for children. The European Data Protection Board published Guidelines 2/2019 on the processing of personal data under Article 6(1)(b) GDPR in the context of the provision of online services to data subjects, on October 16, 2019. They concluded that, on the capacity of children to enter into contracts, (footnote 10, page 6)

“A contractual term that has not been individually negotiated is unfair under the Unfair Contract Terms Directive “if, contrary to the requirement of good faith, it causes a significant imbalance in the parties’ rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer”.

Schools’ statutory tasks rely on having a legal basis under data protection law, the public task lawful basis Article 6(e) under GDPR, which implies accompanying lawful obligations and responsibilities of schools towards children. They cannot rely on (f) legitimate interests. This 6(e) does not extend directly to third parties.

Companies and third parties reach far beyond the boundaries of processor, necessity and proportionality, that should be acceptable under contracts, when they determine the nature of the processing: extensive data analytics, product enhancements and development going beyond necessary for the existing relationship, or product trials.

Data retention rules are as unrespected as are the boundaries of lawful processing. and ‘we make the data pseudonymous / anonymous and then archive / process / keep forever’ is common. Rights are as yet almost completely unheard of for schools to explain, offer and respect, except for Subject Access. Portability for example, is rarely offered at all.

Schools cannot carry on as they do today, manufacturing ‘consent’ which is illegitimate. It’s why many companies in UK education, are processing unlawfully: they rely on consent for their own processing purposes, that simply cannot and does not exist.

We need a strong legislative framework in education that goes beyond data protection, incorporating privacy law, communications law, human rights and guidance for example on procurement, to empower staff and companies to know what is permitted and what is not when processing children’s data from education and to enable a trustworthy environment fit for the future, so that families can send their children safely to school.

Proposed elements for better data practice

The UK needs an UK Education and Digital Rights Act to govern the access to educational information and records by commercial companies, public bodies and other third parties, including researchers, potential employers, and on foreign transfers and takeovers. Clarity, consistency and confidence will be improved across the education sector with a firm framework for the governance and oversight of handling children’s personal confidential data.

1. No surprises, through transparency

- Every expansion of national school census collections and significant changes at local and regional levels, must have public consultation.

- Start fair communications across the education sector with children and families, telling them in an annual report, or on demand, how their personal confidential data have been used from every school census.

- Companies contracted by schools have an obligation to inform the child/family how their data are used. This applies throughout the life cycle of the data processing, not only at the point of collection, and must be in clear and easy to understand language for a child, in line with data protection legislation. We would design a new framework for managing this through schools.

- Each child should be issued with a data usage report on leaving school, listing where their data are, for what purpose, and how long they will be kept and why.

2. Empower families to take back control under the rule of law

- Develop a legislative framework for the fair use of a child’s digital footprint from the classroom for direct educational and administrative purposes at local level, including commercial acceptable use policies. This would deliver clarity, consistency, and confidence to school staff.

- Families must be offered an opt in of school census pupil data third-party reuse.

- Families must be asked for opt in before local authority or other linkage between SATs, nursery, primary, and secondary pupil data and data broker records or other data provided later in life such as from higher education.

- Access to identifying pupil personal data collected at the Local Authority and similar level to the national Department for Education or its programs, providers, research partners, governmental bodies, or regulators would require explicit parental consent, with exceptions for safeguarding in the best interests of a child, and such access would be recorded and available as part of data usage reports.

- Level up the protections for biometric data across the UK equally to protect children currently not covered in Northern Ireland and Scotland by the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012.

3. Safe data by default

- Stop national pupil data distribution for third-party reuse. Start safe access instead.

- Establish fair and independent oversight mechanisms of national pupil data, so that transparency and trust are consistently maintained across the public sector, and throughout the chain of data use, from collection, to the end of its life cycle.

- Special Educational Needs data such as autism, mental health needs, hearing and sight impairments, and disabilities, must be respected in the same way as health data is in the NHS, in accordance with existing special category data requirement.

- The recommendation on persistent identifiers in the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners resolution on e-learning platforms, should be broadly applied, “Consistent with the data minimisation principle, and to the greatest degree possible, the identity of individuals and the identifiability of their personal data processed by the e-learning platform should be minimised or de-identified.”

- End Home Office access to pupil data collected for the purposes of education to restore the trustworthy collection of national pupil data in the school census.

4. Accountability in public sector systems

- Lawmaking and procurement at all levels of government must respect the UNCRC Committee on the Rights of the Child General comment No. 16 (2013) on State obligations regarding the impact of the business sector on children’s rights.

- Any company processing children’s personal data seeking procurement in schools, whether for purchase or as freeware, must demonstrate their accountability for fairness in the design of their technology, as part of that procurement process.

- Introduction of new technology and datasets at scale or with significant effect, require education research ethics committee oversight, pedagogical assessment, and publication of child rights and data protection impact assessments.

- Schools would ensure accountability in procurement by offering consultations, and publishing child rights and data protection impact assessments, and contract terms and conditions, before the introductions of new technology, or data re-use.

- Where schools close (or the legal entity shuts down and no one thinks of the school records [yes, it happens], change name, and reopen in the same walls as under academisation) there must be a designated data controller communicated to processors, and people affected, before the change occurs.

- Families and children must still be able to request error correction and erasure of personal information collected by vendors which do not form part of the permanent educational record. And a ‘clean slate’ approach for anything beyond the necessary educational record, which would in any event, be school controlled.

5. Avoiding algorithmic discrimination

- Algorithms can discriminate against young people, women, and ethnic minorities, or indeed anyone based on the bias of the people who build systems and decision making processes.

- Commission an audit of systems and algorithmic decision making using children’s data in the public sector at all levels, in particular where using or linked with education data, to ensure that individual redress, fairness, accessibility, societal impact and sustainability are considered by-design in public policy.

- Data analytics’ impact assessments, publishing contract terms and conditions, and oversight mechanisms, would increase trust in institutions’ public accountability.

- Algorithmic transparency by default, must be included in procurement processes. If the technology is too opaque and hard to explain to teachers to identify errors, or for families or children to understand, they should not be used at all.

- Any automated marking and feedback processes must be optional, and human-in-the-loop alternative methods, offered with accessible appeal processes.

6. A national data strategy fit for their future

- Design a rights-respecting national data strategy built on principles of data justice by design. Establish a trustworthy framework of controls and oversight for all administrative data use and research, in collaboration with all political parties, civil society, industry, local authorities, third-sector, and other experts.

- Recognise children’s data merit special protection due to potential lifelong effects.

- The rights to control, correct and remove national records about us, must be restored through an opt-in of pupil data third-party reuse or data linkage.

- A data usage report issued to each child on leaving school, must include where their national data are, for what purpose, and how long they will be kept and why.

- A one time national pupil database communication, must Include those 15m who left school, but whose data are re-used by thousands of commercial third parties.

- Core infrastructure dependence ie such as MS Office 365, major cashless payment systems, or Google for Education must be part of a national risk register.

7. Design for fairness in public data

- Ensure fair and independent oversight mechanisms are established in the control of public administrative datasets, so that transparency and trust are consistently maintained in public sector data at all levels, to deliver comparable insights and equality of outcomes.

- In addition, minimum acceptable ethical standards could be framed around for example, accessibility, design, and restrictions on in-product advertising.

8. Accessibility and Internet access

- Accessibility standards for all products used in state education should be defined and made compulsory in procurement processes, to ensure access for all and reduce digital exclusion.

- All schools must be able to connect to high-speed broadband services to ensure equality of access and participation in the educational, economic, cultural and social opportunities of the world wide web.

- Ensure a substantial improvement in support available to public and school library networks. CILIP has pointed to CIPFA figures of a net reduction of 178 libraries in England between 2009-10 and 2014-15.

- End the unsafe use of social log ins. The convenience of social logins depends on data-sharing technologies between the social login “identity provider” and the online educational tool. Implemented poorly, social login can result in excessive collection and disclosure of detailed profile and other identifiable information between the two sites, and the mixing of personal and educational profiles.

9. Horizon scanning

- Ensure due diligence for safety and ethics are integral in emerging technology markets and in competitive takeovers of products that affect UK school children.

- Agreements to terms and conditions of processing at the time of the procurement must also continue to apply after a purchase, merger, or other acquisition of an operator by another entity, and offer a sufficiently fair communication period for change of terms and right to alter or object to new conditions. Otherwise such changes would be reason for end of contract and withdrawal of all data provided.

- Ban facial recognition in schools in line with GDPR decisions in France and Sweden and

- Re-assess the routine use of biometrics in schools such as fingerprints, given ever-growing risks and calls for broader adoption of authoring detection and biometric authentication for identity and remote proctoring.

- Design for age appropriate systems with a consistent, privacy preserving approach to identity.

10. Online harms

- Ensure that children and the most marginalised in society can fully participate in educational, cultural, economic, political, play and other activity online supported by regulation that ensures hate laws and incitement to violence can be acted upon effectively without infringement on participation and freedom of expression, avoiding censorship, or reduction of human rights.

- Promote a rights-respecting digital environment that protects rights to anonymity and identity.

11. Privacy of communications and profiling

- Scale back state surveillance under the Prevent Programme, stopping the mass monitoring of pupils, and collection of communications data, building profiles of individual behaviour.

- Introduce a ban on targeted advertising, for real time bidding adTech, using personal information to create profiles about school children, sell or rent their personal data, or onwardly disclose it to further third parties.

- Processing data in educational products, should not be permitted to serve children or families marketing for product upgrades or additional products.

- Regards access to school software through personal electronic devices, authorities must clarify appropriate uses, limitations and any consequences of use – in particular where software or mobile applications are installed through school.

12. Security

- Oppose any attempts to undermine encryption and creation of “backdoors” into encryption tools or technology platforms, in order to protect our public data.

- Conduct an education sector audit for outdated infrastructure across mission critical systems that expose the sector to malware.

- Consider minimum security standards, such as New York’s Student Data law that includes a requirement to encrypt student data in line with the encryption requirements of the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (N.Y. Educ. Law § 2-D(5)(f)(5))

13. Teacher training

- Introduce data protection and pupil privacy into basic teacher training, to support a rights-respecting environment in policy and practice using edTech and broader data processing, to give staff the clarity, consistency and confidence in applying the high standards they need.

- Ensure ongoing training is available and accessible to all staff for continuous professional development.

- Support at least the same level of understanding across schools, as must be offered to children in developing core curriculum requirements on digital literacy and skills, as recommended by the Select Committee on Communications, in the report, Growing up with the Internet (2017).

- Shift the power balance back to schools, where they can trust an approved procurement route, and families can trust school staff to only be working with suppliers that are not overstepping the boundaries of lawful processing.

Processing and procurement

We need a new physical infrastructure for procuring the edTech route into schools, and oversight of the data out of schools through to companies, and for statutory obligations.

Processors must only process for only as long as the legal basis extends from the school. That should generally be only the time for which a child is in school, and using that product in the course of their education. And certainly data must not stay as today, with an indefinite number of companies and their partners, once the child has left that class, year, or left school and using the tool. Schools will need to be able to bring in part of the data they outsource to third parties for learning, if they need it as evidence or part of the learning record, into the educational record, to enable a single point of contact.

The due diligence in procurement, in data protection impact assessment, and accountability needs to be done up front, removed from the classroom teacher’s responsibility who is in an impossible position having had no basic teacher training in privacy law or data protection rights, and the documents need published in consultation with governors and parents, before beginning processing.

That needs to have a baseline of good standards that simply does not exist today. That standards’ assessment would also offer a public safeguard for processing at scale, where a company is not notifying the DPA due to small numbers of children at each school, but where overall group processing of special category (sensitive) data could be for millions of children. Confidentiality by default that you may expect inside a school, is compromised within new, all-MAT-access models, and outsourced to companies.

Where some procurement structures might exist today, in left over learning grids, their independence is compromised by corporate partnerships and excessive freedoms. A fair playing field for all, should be set out in legislation, as FERPA does for the US.

What would better look like

Our data ecosystem needs a shift to acknowledge that if it is to be safe, trusted, and GDPR compliant — a rights respecting regulation — then practice must become better.

That means meeting children and families reasonable expectations. And for life.

National data uses would become fairer and more lawful, and increased trustworthiness would mean better data. Any opted out data from secondary re-uses would be compensated for, reducing any significant effect in a population of multi-millions. A better trusted, accurate, applicable data set than today, would be a win for everyone.

The expectation of a rights-respecting environment should not be a postcode lottery.

If we send our children to school, and we are required to use an edTech product that processes our personal data, it must be strictly for the *necessary* purposes of the task that the school asks of the company, and the child/ family expects, and not a jot more.

Schools also have a responsibility to be rights’ respecting and to ensure a suitable alternative offering of education without detriment to the child, should families or the child exercise the right to object to particular data processing, or a particular product.

And wider issues are those that stem from so much of a state education system being outsourced to commercial providers. Proprietary systems, closed commercial terms, closed data processing and retention models, instability and obsolence of software and hardware, budget wastae and environmental costs, if apps or plaforms functionality are shutdown at short notice. Exclusivity rather than interoperable open standards.

Could we look to build on procurement models that already exist? The U.S. schools model wording for FERPA would fail GDPR tests, in that schools cannot ‘consent’ on behalf of children or families. In practice the US has weakened what should be strong protections for school children, by having the too expansive “school official exception” found in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (“FERPA”), and as described in Protecting Student Privacy While Using Online Educational Services: Requirements and Best Practices. There would need to be better coverage of loopholes, to prevent companies from working around safeguards in procurement pathways.

Borrowing on Ben Green’s smart enough city concept, or Rachel Coldicutt’s just enough Internet, UK school edTech suppliers should be doing ‘just enough’ processing, not more.

While how managing children’s data in education is done in the U.S. governed by FERPA law is imperfect and results in too many privacy invasions, it offers a regional model of expertise for schools to rely on, and strong contractual agreements of what is permitted.

That strategy we could build on in the UK. It could be just enough, to get it right.

[This text is adapted from a post by Director, Jen Persson, published in November 2019 The consent model fails school children. Let’s fix it.]