Google education products under scrutiny: lawsuit in New Mexico and Norway DPA investigates.

edTech legislation / February 24, 2020

The Norwegian Data Protection Authority has announced it is investigating whether it is legal to use Google in schools.

The US state of New Mexico launched a lawsuit on February 20, 2020, which says that the use of Google Education and other Google products, “comes at a very real costs that Google purposefully obscures.“

The Google costs

The googlification of state schools worldwide has been rapid. In Bergen, Norway, alone, 14,000 school children each have Google Chromebooks, according to the AftonPosten.

And “as the variety of Chromebooks has expanded, so too has the range of students using them. Google recently announced that more than 25 million teachers and students are using Chromebooks for education globally, and 30 million teachers and students are using Google Classroom, along with the 80 million using G Suite for Education. “

Google keeps the breakdown of any known UK numbers secret. (Yes, we’ve asked). UK schools integrate Google products with schools’ core information management systems Thousands of pupils’ and staff personal details can be extracted to Google in a few clicks, to set up personalised accounts.

How much the freeware actually costs schools, in terms of managing the installation and integration or hardware management is unpublished.

Some of the privacy costs to children are not new, but little discussed in the UK as yet. In 2017, two years after US digital rights group EFF filed a 2015 US federal complaint against Google alleging that it was “collecting and data mining school children’s personal information, including their Internet searches,” the EFF issued a new status report detailing how Google is still working to erase minor students’ privacy “often without their parents notice or consent, and usually without a real choice to opt out.“

The New Mexico state case focuses on Chrome Sync and Additional Services.

Here was Google’s 2015 response to EFF in a blog. It confirmed the use of “data aggregated from millions of users of Chrome Sync and, after completely removing information about individual users, we use this data to holistically improve the services we provide. “

The reliance risks

Google doesn’t make public how many UK school staff the company has given its product training. They return to schools as “google educators” or ambassadors, with a mission to spread the good news. Grids for learning can also be active promoters.

The UK has significant but hidden dependence on Google and similar big tech products. Core infrastructure dependence on single providers of key systems such as communications, curriculum delivery and cashless payment systems should be on risk registers. The level of risk to the delivery of UK education system, if Google and co. switched off tomorrow, is opaque.

How reliant we have become on the US giant shaping our school systems and child/teacher interactions has yet to be discussed as part of education sector debates.

Children’s rights and the problem of consent

In paragraph 8 of its general comment No. 1, on the aims of education, the UN Convention Committee on the Rights of the Child stated in 2001:

“Children do not lose their human rights by virtue of passing through the school gates. Thus, for example, education must be provided in a way that respects the inherent dignity of the child and enables the child to express his or her views freely in accordance with article 12, para (1), and to participate in school life.”

Those rights currently unfairly compete with commercial interests. Data protection law alone, is weak protection for children in compulsory education. This is why we are calling for a UK Education and Privacy Act, to create a rights’ respecting digital environment across the UK education systems.

Google appears to be arguing in the press on this New Mexico case so far, and in a 2016 letter to Congress, that it is schools’ fault to fail to gather ‘verifiable consent’ from legal guardians. Google’s problems however are two-fold in this regard.

(1) that they have known this for years, and failed to accept responsibility or be held accountable for it.

(2) consent is in any case, invalid for Google’s data processing from school children, and their guardians, both in the sense of data protection law, and from an ethical perspective, since it involves children, and an imbalance of power.

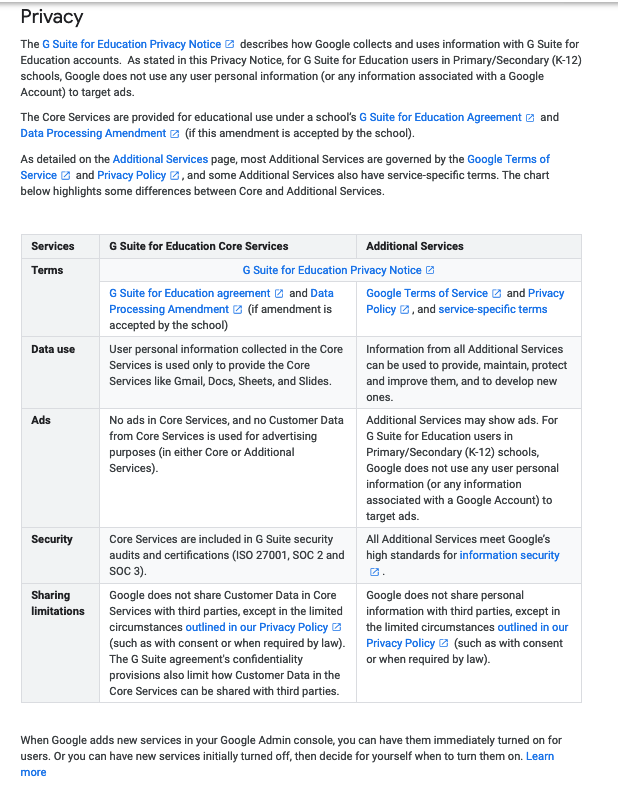

Google splits its G-Suite product into “core” and “additional” services. It offers different levels of service support to schools using their products, but it also allows Google to do different things with the data between the two groupings. Its terms says consent is necessary for schools to collection for the Additional Services.

Google simply has no consent collected from families, or children. Rights groups on both sides of the Atlantic, including EFF and ourselves, have told them so in recent years. Why they need consent, and cannot operate on only the basis of public task and contract with the school, is that the company’s processing is excessive, beyond what the school requires for its own needs or those of the children using the product, into what Google wants to do with children’s data such as product development.

So let’s be clear that Google is asking not in fact for something that is unrealistic or difficult to obtain, but simply does not exist and cannot ever exist at all in education.

Even if Google gave schools a way to gather ‘verifiable consent’ (which it does not today) it would not be lawfully valid under GDPR or UK data protection law due to —

a) children unable to give freely and informed due to complexity of processing,

b) the power imbalance makes consent invalid, even if you could understand it easily means both young people and parents not wanting to say no and be a problem,

c) schools not offering any meaningful alternative if it is refused.

If you cannot say no without detriment, you cannot meaningfully say yes.

We asked Google in Europe in November 2018 about this, pointing out that:

“Reality in practice, is that at best, if consent is asked for at all, consent is manufactured as a tick-box exercise. Better but rare school policies in the 400 we have seen, contain a permissions page in the child’s Admissions booklet which lists the Core Google Apps a school uses. Many policies at many schools do not tell parents which apps are in use at all. Those which do ask for ‘consent’ are simply asking for a signature but no consent process, since refusal is not an option.”

“Given this bundled process and lack of consent as a legal basis, we do not believe that schools or Google have a legal basis for processing children’s data in England for additional services, in the way that Google goes on to use children’s data for further purposes.”

The Public Policy and Government Relations Manager pushed back against our criticism, insisting that the Terms and Conditions were clear. We still dispute this. Especially as far as terms ‘understandable by a child’ go, under GDPR and UK Data Protection law. For example its statement, “We may share non-personal information publicly and with our partners – like publishers or connected sites. For example, we may share information publicly to show trends about the general use of our services, ” does not explain who they are, what their purposes or retention period is. There is also a fundamental refusal to accept their disconnect with reality. Their policy says, “If a parent wishes to stop any further collection or use of the child’s information, the parent can request that the administrator use the service controls available to them to limit the child’s access to features or services, or delete the child’s account entirely, ” which is simply untrue. No school we know, in over 400 policies reviewed, permits this.

Manufacturers of toys with lead paint are not allowed to say it safe, and carry on unregulated, simply because they tell people, do not eat our products.

In terms of the question of the lawful basis for data processing, it is not a consent process that is missing. It is because of Google’s processing by design that that exists and goes beyond the school’s needs, into the company’s wants, that is their problem. Because consent is unavailable to them, they need to change their business practices.

And let’s be clear, this is not a problem only for Google. It’s just not been enforced yet in the UK. The challenge of consent, contract and confidential data in schools needs regulated differently, and must respect parental / child rights, in supportive ways.

Further questions of transparency, trust, safety, and ethics

Google’s role in data transfers and Cloud storage, apps, operating systems and email are often opaque to schools in contracts with the tech giant. Schools can’t generally edit the conditions, but have to take on Google products on the company terms, or nothing. How does Google use and store personal information? What is tracked in additional services, when and why? How long may it be kept? Where? How many sub processors may there be? Families don’t get told or have any way to exercise a right to object.

Google dismisses issues, and tries to push back accountability to poor school configuration choices, but the question should be why poor configuration and privacy choices are possible at all.

Some of the issues that parents have raised with us, include Google for Education giving primary school children an email address that parents are not informed about. Or that they have no choice over, and at a much earlier age than families may have wanted. Parents are concerned that these can be used to email outside the school, or connect with an external Google account ID (i.e. an id that the child has been sent) as their “partner” in Google Photos for example, sharing every photo they have or will take in future. It is possible for avatars to be seen by thousands of users within the school, and even stuck permanently where avatars are used in social log ins or online comments. Stripping photo geolocation seems to be turned off by default. Contact beyond the school setting, may be possible using almost any Google app in the education suite, Docs, Drive, Sheets, Slides, Photos, Groups, Calendar and products can allow voice data sharing as well. Google Hangouts provides a very easy way to validate either the email addresses (Google or not, incl ones used as Apple IDs for school iPads) or Google IDs.

Safety questions over the exposure children have imposed them through this, for example in Google Hangouts, have been asked in Australia. Such exposure doesn’t need mitigated, but stopped by design.

These are some of the questions authorities in Australia, and in Switzerland began to investigate last summer, and that the Norwegian Data Protection Authority is now questioning too. The answers they come up with may be crucial not only for Norwegian schools, but for the UK and Google in the classroom worldwide.

We hope that Supervisory Authorities will now address:

- the flawed consent model, and that consent is in any case invalid

- excessive due diligence burden on schools and families

- lack of edit control of Ts&Cs

- excessive processing for company not school purposes (that should end)

- analytics and user tracking are not a form of service improvement and should not be necessary for performance of a contract

- lack of informed processing (that should start and be annual of what was done)

- over-complexity of information, unreadable by a child (required under GDPR)

- in-country data processing ,retention, and storage

- ending voice and special category data retention

- driving a rights’ respecting environment in education, based on ‘just enough’ processing

References:

- New 2021: Don’t Be Evil: Should We Use Google in Schools? Krutka et al. https://link.springer.com/epdf/10.1007/s11528-021-00599-4

- Google blog for numbers: https://web.archive.org/web/20200222125112/https://www.blog.google/outreach-initiatives/education/all-types-chromebooks-all-types-learners/

- Case: https://www.scribd.com/document/447984330/State-of-New-Mexico-v-Google

- Norway: https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/pLvba6/datatilsynet-undersoeker-om-det-er-lovlig-aa-bruke-google-i-skolen

- Our 13 sets of recommendations: https://defenddigitalme.org/2020/02/towards-the-uk-educational-rights-and-privacy-act/

[updated on 24 February, 2020 to restore a previous amended version]

[updated 24 March 2021, to add link to research paper, Don’t Be Evil: Should We Use Google in Schools?]