The Education Act 1996 is twenty-four today

Campaign MyRecordsMyRights / July 24, 2020

The Education Act 1996 is twenty-four years old today. It is out of date for the digital age, in particular when it comes to its contents on data.

Upgrades to the Act have all been negative

Since it was enacted on the 24th July 1996 over twenty statutory instruments have expanded the remit of Clause 537a, almost all without through scrutiny going through a negative process, and nothing in the Act addresses the wider picture of any digital approach in education; such as standards of quality and safety, or inclusion and accessibility.

For the list of Statutory Instruments that have incrementally expanded which data can be collected on children since 1996, and on a named basis, since 2002, see Annex to question HL2783 . [attached in link from the answer] On top of the termly school census collections, come all the children’s individual records from standardised tests so we need to add to this list with two more new ones, the Multiplications Times Tables Test added in 2019, and Reception Baseline Assessment expected in 2020.

Changes to collect more data at national level, but none benefit the child

When it comes to data, the results of those changes is a year-on-year increase in the volume of national data collections, and expansions in how data are re-used for purposes beyond the school. None is for the direct benefit of the child.

Prior to 2007, the Schools Census dataset was known as the Pupil Level Annual Schools Census (PLASC). Comprehensive PLASC data was first collected in 2002, including individual pupil names which government may have had ‘no interest in’ in as individuals in then, but fast forward 13 years later and the Home Office is using them to match with their own records. That is ongoing. It should end with data protection enforcement of purpose limitation.

Data are given away to others, but you can’t access your own record

Cumulative changes to laws by successive governments have enabled the release of individual and named data.

The most significant changes when it comes to the use of the data, were introduced by Michael Gove as Education Secretary in 2012-13. He changed the Act to enable what pupil data could be given out to third parties, identifying data at individual pupil level, and also expanded which third parties, the ‘prescribed persons’ to whom it could be given.

Responses to a brief consultation over the Christmas holidays 2012, concluded that press and others getting raw data would be a mistake, and noted that the consultation made no effort to involve under 18s, or the people whose data it was. The plans carried on regardless.

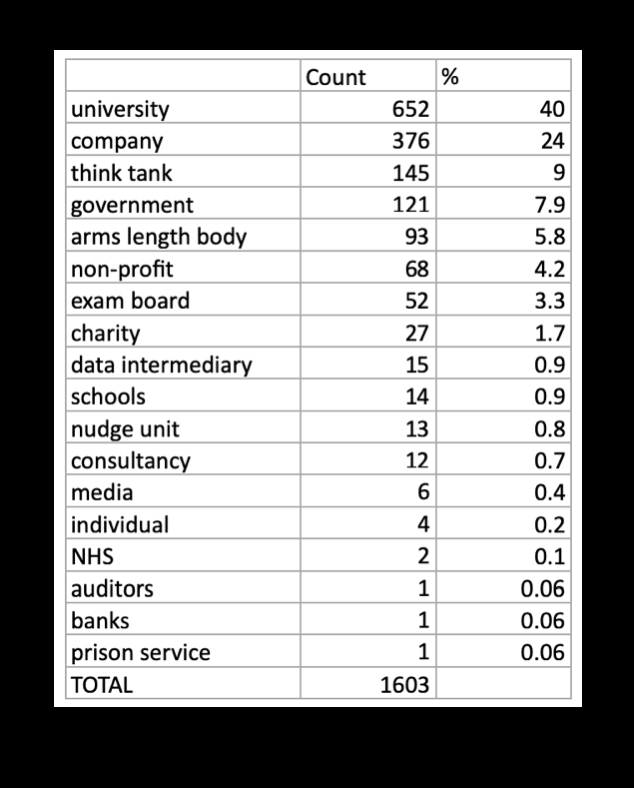

Since then millions of records have been given away over 1,603 times. No one knows how many pupils’ records have been given away in each of those times, because the Department doesn’t track it.

If you are aged 37 or under, in England and Wales, or have attended state education including evening classes and further education, the National Pupil Database and other national Learner Records are about *your* state school records and personal details.

But the Department is unable to tell you which releases give away your own child’s data. “The Department does not maintain records of the number of children included in historic data extracts, “so we do not know exactly who has it for which purpose.

Commercial companies, think tanks, charities, academics, journalists and other government departments can get hold of identifying confidential school data, since the government started giving it away. Identifying and sensitive data were given to journalists at BBC Newsnight, The Times, and the Telegraph.

As far as we are aware, no one who left school since 2012 when the law was changed has been contacted to be informed of the news uses of their personal data in these ways that they would not expect simply from having gone to school.

That’s every child who was in school in the fourteen years between 1998 (when pupil level data began to be collected) and 2012 (when pupil level data began to be given away to the new third parties). It was impossible for them to know that the government started giving away their personal data in 2012 because the Department didn’t tell them. Schools can’t tell them, because the children had already left.

No one expects the government to give children’s data away, so families don’t look for it either, and privacy notices while improved in 2017, still fail to deliver in their aims. In February 2018 we commissioned a poll through Survation who asked 1,004 parents of state-educated children age 5-18 about their understanding of data used in schools. 69% of parents said they had not been informed the Department for Education may give away data from the National Pupil Database to third parties.

Yet despite all this given away about you, there is no decent process to see your own national record. We’ve laid out the steps how you can do so, making a Subject Access Request here in step 3. Let us know how you get on. And write to your MP if you agree, to tell them you want change too.

What needs to change

The use of children’s data and central data collections is not only a national question, but one that needs addressed for schools themselves. Most data is funnelled upwards and is useless to schools which leads to the design of well intentioned but likely unlawful approaches. Government use of data is often punitive, or poorly understood, creating fiction from facts. The standardized tests that Ministers insist are only “tests for the schools rather than individual children,” are used as reference scores for GCSE results. It seems absurd if you consider the questions of grade inflation, discrimination and bias, and teaching to the test. SATS scores are even more dangerous as risk indicators in health or predicting risk of domestic violence and abuse. Wide deviations from their intended purposes, and not fit for the new ones for which Local Authorities are linking them with other datasets.

Vast amounts of data are sent out from school information management systems to thousands of apps and platforms based across the world, data that teachers and families never see and have no idea how to control.

We need a new accountability system that works. And a way to make new guidelines and data protection better applied and understood across the sector, but creating a rights’ respecting environment in education goes far beyond data protection law.

We need acceptable standards of what is and what is not permitted to do to children using technology in state schools. In terms of advertising, behavioural nudge, mental health prediction, and surveillance of their Internet use in the home. This considers the quality, health and safety aspects of emerging technologies, emerging harms and clarifying obligations in procurement, the role of the parent and the child. the current strategy is scattered in a piece meal approach spread across the Department with no conceivable strategy between the six edTech apps recommended for Early Years, and edTech demonstrator schools or edTech export promotion. We in civil society can keep playing whack-a-mole with individual companies, or try and fix capacity in single schools, and the Regulator can try to play catch up; or we can build a fair playing field for everyone to compete with clarity, consistency and confidence that is fit for the education system of today and beyond, not that of 1996.

Without an infrastructure there is no consistent and qualified support for schools to build on, to avoid children in England being used by apps that children in Dundee have been protected from.

On the 24th birthday of the Education Act 1996 we have proposals for a new Education and Digital Rights Act.

It should cover a range of content to address topics including:

- Digital disadvantage: remote learning has raised issues like never before, of provision, quality, and accessibility in terms of infrastructure and lack of standards or support for children with SEND. Too many children are digitally disadvantaged today leaving school and college, or going into the workplace, and in ways that many do not see, though corporate discrimination via data misuse.

- Procurement practice: currently a risk not only to individuals and communities, but to the public sector infrastructure of the education system: there’s also a range of key failings across the edTech sector that need change, in particular on children’s rights on which we submitted to the education select committee this month.

- UK edTech Export strategy: we need to have high standards in place not only for our own children, but as the government seeks to increase UK edTech exports around the world so as to ensure what we sell to others is safe, pedagogically proven, value for money, and trustworthy for teachers and parents. Emerging technologies are increasingly invasive in precision education that “overtly uses psychological, neurological and genomic data to tailor or personalize learning around the unique needs of the individual.“

- Build a support structure: to build the capacity and confidence of schools, suitable for understanding the complexity of AI, or apps claiming to use cognitive science and its implications, enabling due diligence and legislative knowledge and parental support, and contract management with qualified companies permitted access to the state education sector, as FERPA provides at state level in the U.S.

- Empowering parents and children to understand and control their digital lives: Design a radical overhaul of how national data collections happen, including the introduction of consultations on national standardised testing, and school census expansions that affect millions of children. No more negative secondary legislation that rushes through significant changes without scrutiny. Ensure a national opt out of data re-use and distribution for non-educational purposes. Promote data protection and privacy training in basic teacher training and professional development, to build a rights’ respecting environment from the ground up.

It’s time to overhaul the Education Act for children in the digital environment.

Background reference

You can view the third party release register here. Note it was split into two lists in 2017, and older releases archived here. It is now in 7 separate publications. We have campaigned for a regular and frequently published list to improve transparency. We were successful in getting transparency of police and Home Office use added to the register. We have also asked for more information about the releases and how long the data may be used for by third parties, as we have demonstrated in 2015 that data was not destroyed as should have been after use. This destruction due date was added to the register and published in May 2016 for the first time. This transparency may help reduce the risk of errors going unnoticed for a long time. However it does mean there is lack of consistency in the release formats over time.

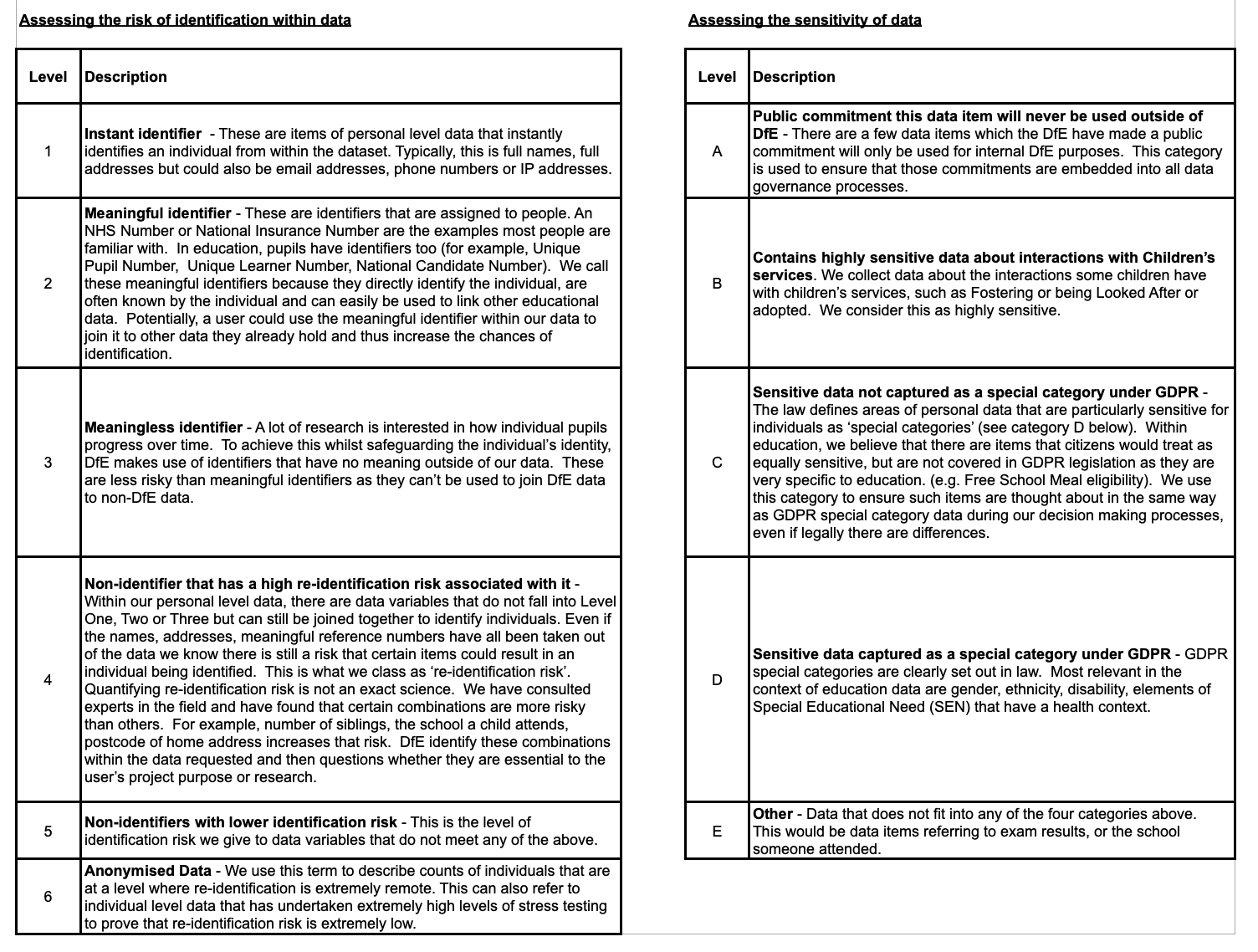

Our analysis of the six publications of the register of identifying pupil data releases since 2012 until October 2019 has shown data quality is poor with errors and duplications. We are currently analysing the most recent publication from June. We estimate 40% of use by academics, a quarter by companies, 8% by government, 6% by charities and non-profits, and after exam boards, the Nudge Unit, data intermediaries and schools a handful of others. While a range of media were given data in 2012 and 2013, there have been few since. All releases are identifying data, as described in the DfE data classifications table.

Source: DfE External data shares, tab ‘classifications’. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dfe-external-data-shares