The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts (PCSC) Bill briefing

National Pupil Database / May 20, 2021

The Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts (PCSC) Bill, is now under scrutiny at the Committee Stage Parliament. We are delighted to have read and support the Alliance for Youth Justice recommendations as pertain to broad areas of youth justice and children’s rights. We also share Privacy International’s concerns with digital data extractions as well as those we shared in a joint-briefing led and set out by Big Brother Watch. That makes broad recommendations on aspects of the Bill as pertain to digital rights, including extractions of data from mobile devices from children.

Other organisations specialise in the needs of the Traveller community, or the right to freedom of speech and expression so we have not briefed on these although there are far reaching implications for children. Our own Committee Stage briefing is narrowly focussed on the aspects of the Bill that directly affect only the digital, identity and data rights of children, and we make six recommendations.

The Bill will expand existing disadvantages for children through its expansions of powers on Stop-and-Search, the Prevent Programme, and measures targeted at the Traveller community. This has impact on discrimination and equality rights, and a wide range of children’s other rights such as the right to freedom of speech, thought conscience and religion, the right to participation, and the right to be heard. Considering the nature and scope of these effects, we believe that a Child Rights Impact Assessment is necessary. While the Best Interests of the Child got a token mention at the very end of the very weak Human Rights Impact Assessment that accompanied the Bill, there was no assessment, nothing was found of what effects it would have, nor was any remedy or safeguards proposed as a result.

If the UK government starts criminalising ‘nuisance’ noise, more children will be caught up in such definitions by exercising their right to peaceful protest such as Fridays-for-Future, or exam protests outside the DfE in the summer holiday of 2020.

We therefore recommend raising the age of criminal responsibility to be consistent across the UK, and aligned with civil society recommendations made in the 2020 submission to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child review of the UK and the work on this of the Child Rights International Network. The age of criminal responsibility in England today is 10, and in Scotland 12. The UNCRC defines a child as anyone under 18. A compromise proposed by civil society would be age 14.

The Bill is also inconsistent on who is defined as a child. We recommend a review of the drafting to address inconsistencies in the Bill in the age definitions of a child, to be aligned with the UNCRC definition of anyone under age 18, except where provided for with safeguards in law, or the age of majority is reached earlier in law.

The proposed powers on digital extractions from children’s mobile phones, are particularly problematic (Part 2, clauses 36-42 and Schedule 3) as they do not take into account the power imbalance between police and children. While adults are permitted to decline so-called “digital strip searches” wherever the police are using consent as its lawful basis (not applicable for suspects in crime for example) a child may not. An adult not known to them, may “consent on their behalf”. This is nonsense since consent would be invalid, because it could be neither informed nor freely given (a) by the data subject (the child) and (b) by any other data subjects who may be involved (about whom data is on the child’s phone). Therefore, while we also believe consent at all in such a power imbalance is very difficult to navigate, it should, if at all, only be able to be given with the support of a known and trusted adult, such as a relative or guardian. The Bill needs amended to prevent consent being from any adult, but only someone known and trusted by the child. Additional safeguards are needed to narrow the search for targeted contents, not “fishing expeditions” as recommended by the ICO in 2020. and limited access by a foreseeable number of people.

We recommend removing the new powers in Part 2, Chapter 1, Clause 15 Disclosure of information and Clause 16, Supply of information to local policing bodies . Clauses 15 and 16 are unnecessary, as existing functions and data protection law written exclusively for law enforcement purposes was only recently adopted in 2018 and is compatible, except for the caveat in 16(6). The question to ask is: What does this aim to do that is not already lawful today? These clauses require public bodies to supply police with personal data on demand. If a request would contravene data protection law, the new duty of 16(6) is to be taken into account. “16(6) But subsection (4) does not require a disclosure of information that— (a) would contravene the data protection legislation (but in determining whether a disclosure would do so, the duty imposed by that subsection is to be taken into account)”. This is tantamount to saying that this clause is a get-out-of-jail-free-card for police to breach data protection law. The Law Enforcement Part 3 of UK Data Protection Law only came into effect in 2018, designed with ample permissions specifically for law enforcement. This Bill should not create workarounds to avoid that.

We have also been deeply disturbed by the revelations in the Spycops enquiry, that deceased children’s identity data has been misused by police. UK Data Protection law only applies to living persons, so the practice of using dead children’s identities without the knowledge or permission of parents might continue unless explicitly made unlawful. This practice causes harm and distress to relatives affected by data processed about a deceased child. This must end. We propose a new amendment to protect families from the abuse of deceased children’s identities and personal data by (undercover) police officers, banning the practice. This Bill offers an opportunity to do the right thing.

Who “the police” includes, is changing rapidly with the collaboration across private providers and access by police to tools such as Amazon Ring, or to supermarket loyalty card records, commercial data brokers, and surveillance of social media and wider data sources. There is direct police presence in schools, and there is widespread use of equipment for the indirect policing of behaviour that may be shared with law enforcement, such as CCTV, bodycams, biometrics and digital monitoring in schools. Law enforcement is increasingly seen as applying to immigration enforcement with data access and repurposing of school records for the purposes of the Hostile Environment. ”How” the police operates is changing rapidly with technology and with too little scrutiny and oversight. The National Law Enforcement Data Service (NLEDS) is running late, but “the “mega-database” is grown from the combination of the Police National Computer (PNC) and the Police National Database (PND), as well as the DVLA, and immigration databases and biometric systems. All to be joined up through a common interface. Even though intelligence data may not be very smart, the police are looking to add more Artificial Intelligence powers to their portfolio by adopting live facial recognition technology.(The consultation closes on 27 June 2021.)

The children of today are growing up in a policing environment that is ever more datafied, quantified, and seen through the lens of a computer analysis, out of context. Police actions are guided by Codes of Practice that are out of date and unfit for purpose in the digital environment. Our March 2021 submission to the Police consultation on a Code of Practice for Information and Records Management highlights some of our reasoning why. If we fail to make our laws underpinned by human rights and compassion, then children will be deeply disadvantaged in the world that is ever more mechanistic and automated and that fails to take into account the nature of human beings, in particular children developing into adulthood, and the safeguards needed due to their vulnerability.

The Bill should offer an opportunity to make better law for children where they come into contact with the criminal justice system, but this does not do that. Instead, the Bill takes a more punitive approach to processes for children and fails to address children as rights’ holders who will be significantly affected by new legislation. This is a step backwards for children’s rights, not forward, and needs to be corrected.

A great deal in the Bill is so problematic that we would, if given a free choice, rather not have it passed at all. And we are not alone. It is important to note that Martin Hewitt, chair of the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), told a parliamentary committee police leaders had not requested a change to the law as regards Travellers and believed current powers to be sufficient, as reported in the Independent.

However, if the government chooses to proceed, it should do so only in ways that respect children as rights’ holders. The legislation must ensure recognition of the role of police as duty bearers towards children and offer a framework to protect, respect and provide remedy for children’s rights.

####

- Download the summary briefing on the Police Crime Sentencing and Courts Bill narrowly on children, data and digital rights [download .pdf 169 kB] 5 A4 pages

- Download the skeleton version, 1,500 words (3 A4 pages) [download .pdf 125 kB] submitted to the Joint Committee on Human Rights

- Download a joint full Briefing on the Police Crime Sentencing and Courts Bill (led and drafted by Big Brother Watch) [download .pdf 161 kB]

- Our submission to the March 2021 Police consultation on a Code of Practice for Information and Records Management [download .pdf 225kB]

- Word version submitted to the Committee. [link]

- Amendments updates [link]

Separate background

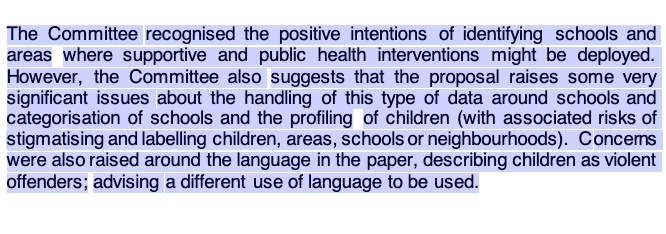

- Birmingham Mail (March 2021) Concern at West Midlands Police proposals to use crime data to identify young ‘violent offenders’ in school catchment areas [link]

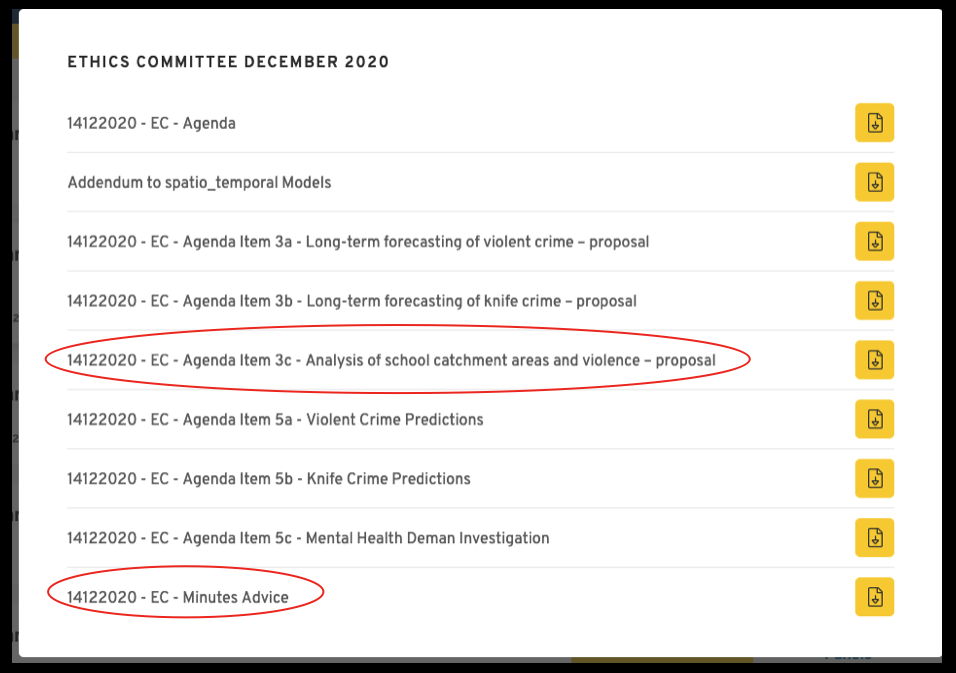

- Report to West Midlands Police’s Ethics Committee, titled ‘Analysis of School Catchment Areas and Violence’. [December 2020, meeting materials] [Read the Proposal and Ethics Committee response via link and see which documents highlighted as below]

- Police use of live facial recognition technology – consultation closed June 27, 2021

- ICO Investigation report: Mobile phone data extraction by police forces in England and Wales (2020)