The Skills and Post-16 Education Bill: More data for them, but no more control for us

Blog / June 15, 2021

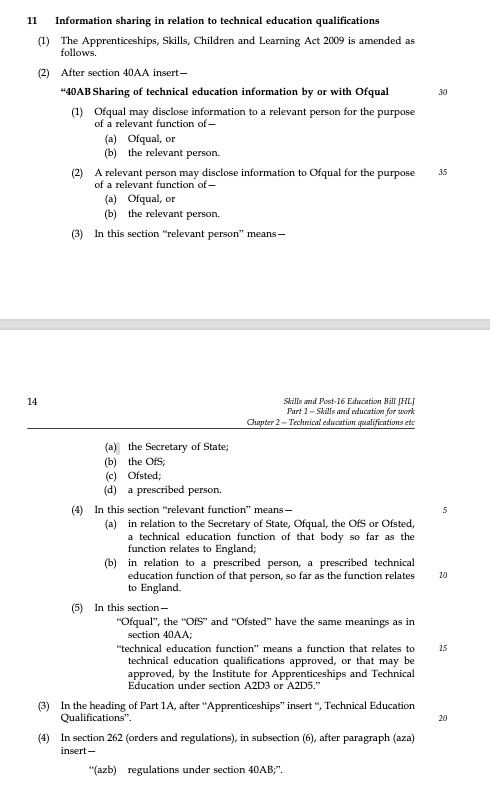

The Skills and Post-16 Education Bill [HL] second Reading today, June 15, 2021 contains Clause 11 about Information sharing in relation to technical education qualifications. According to its notes, the territorial extent includes all of the UK.

The Bill is wide-open to misappropriation of students’ personal data.

It needs:

- An obligation to publish a register of use by data controllers, joint-controllers and their processors.

- Personal data should not be distributed, the data should stay in safe settings only, and secure access distributed.

- Protection from further onward access or distribution, to further sub-processors through the prescribed persons or relevant body who are not listed on the face of the Bill.

- A Code of Practice that reaches across all these bodies and prescribed persons, made open to public consultation.

Download our full briefing .pdf 178kB

Download our skeleton outline (2 pager) 120kB

Updated: October 14, 2021

![]()

The release of individuals’ identifiable data in Technical Education was changed in legislation in 2017. Part 3, s40 of the Technical and Further Education Act 2017 changed what data could be collected by the Secretary of State. Now this Bill changes how it can be handed out and to whom, and why, and it is all rather vague. It must be tightened up.

In the Skills and Post-16 Education Bill,“This clause inserts new section 40AB into the 2009 Act. It supports effective collaboration between Ofqual and other bodies with functions in relation to technical education qualifications, by introducing information-sharing provisions similar to those relating to the Institute under section 40AA of the 2009 Act.

“It empowers Ofqual to share information in relation to technical education qualifications with the Secretary of State, Ofsted and the Office for Students, as well as with other bodies that the Secretary of State may prescribe. It also allows these bodies to share technical education information with Ofqual.This information sharing may support the technical education functions of Ofqual or the other relevant bodies.” (our emphasis added)

As with all recent legislation and data policy from government, the bill overrides consent and there are no guarantees on how data may be used by the ‘prescribed persons’ who are unrestricted and undefined in the Bill, and for vague purposes that do not preclude commercial use. That, “could undermine applicants’ trust in the admissions service, degrade the quality of data collected, and potentially deter some people from applying to university altogether,” according to UCAS in 2017 when talking about the changes made to the Higher Education and Research Act (Point 25, UCAS evidence to Committee in 2017).

This Bill on data in Technical Education could usefully learn lessons from those similar historic changes in Higher Education.

In the July 2018 Motion of Regret debate on the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 (Cooperation and Information Sharing) Regulations 2018 Lord Watson of Invergowrie called on the government to carry out a privacy impact assessment on the Regulations.

This assessment is also missing from the The Skills and Post-16 Education Bill [HL].

He made the point that, “during the passage of the Higher Education and Research Bill, noble Lords and MPs raised concerns about the powers in the regulatory function of the Office for Students and questions of institutional autonomy. ”

This Skills Bill again expands the powers given to the Office for Students through their expanded data access.

Lord Watson said in debate on July 2018, “They create for the Office for Students to grant access to students’ confidential data to a single commercial provider..the purposes for which the data may be used remain open and vague.”

The Skills and Post-16 Education Bill [HL] has the same problem.

This Skills Bill once again leaves open the question of who may access the data in future without further consultation, since in future they can add, “other bodies that the Secretary of State may prescribe.”

Lord Watson said in debate on July 2018, “We have a number of concerns, not least that, as I said, there has been no parliamentary debate or public consultation.”

This new Skills Bill once again sidesteps any public consultation.

What could be different and what would better look like?

The government appears to have no intention to learn from the past but some recent legislation usefully points the way to how it could do so.

Who can receive personal data, for what purposes, and the safeguards on its use must be tightened up and transparency increased.

The Digital Economy Act 2017 made registers of public admin data sharing compulsory. While ROPA requirements under data protection law mean a register of processing is already required there is no obligation to publish it or make it available to data subjects and external scrutiny. It also put in place a bar on further distribution. (See the Digital Economy Act 2017 c. 30 Part 5 Chapter 5 Section 66.)

This Bill has no such requirement to publish a register of use, and it must be added.

Personal data should not be distributed, the data should stay in a safe setting, and secure access can be distributed.

This Bill has no such requirement to protect data from further onward distribution, and it must be added.

The somewhat sneaky changes to collect more data at national levels, and increasing the numbers of bodies it can be passed around, need to end. People want more control over how data about them is used and by whom. More transparency about uses. And more human accountability for decision-making. This Bill offers nothing in this area and shows once again how out of date the government approach is to public administrative datasets.

The government must acknowledge that they are overruling what people want time and time again. There is no democratic decision-making about the use of student data involving students, the people the data are about. Or pupil data. Or indeed anyone who uses a public service, and therefore creates administrative data as a result of interactions. Public engagement research over the last 10 years, finds the same over and over, that people disagree that the records of their lives are a commodity to exploit. They generally agree overwhelmingly on the red lines of what the public interest should permit.

In 2015 UCAS carried out a survey which had 37,000 responses. “A majority of UCAS applicants agree that sharing personal data can benefit them and support research into university admissions, but they want to stay firmly in control.” A large majority, 90%, of respondents said they wanted to be asked for their consent before their personal data is shared with anyone outside of the admissions service.

The DfE ICO audit is still ongoing, and there have been no satisfactory conclusions in the “access by gambling companies” in January 2020. The OFS, UCAS, and Higher Education funding bodies decision making bodies around data are still opaque, even though it now includes students religion and sexual orientation in their named records. The DfE external record of data shares is not a design to follow, with its now 8 separate archived versions. Users cannot find out in which of the over 2,000 releases of millions of identifying records, their own or their child’s records were in. Meanwhile HESA has at least begun a record of distribution although it is also a little lacking as yet.

Students need additional safeguards at least in retrospect while the infrastructure does not yet exist to control collection and the data distribution during its life cycle.

There must be serious consideration given with urgency on enabling how public administrative datasets are managed. Personal data from the public, from pupils to students and throughout the data life cycle, is easily taken and passed around and lost, or stolen, or given to gambling companies and access credentials left open, unaudited, to companies that have gone bust.

Yet the mechanisms to manage our lawful rights, to permit uses, correct mistakes, and give or withhold consent for further purposes not defined at the point of collection do not exist today by any adequate or consistent routes.

The Government must enable that infrastructure to be put in place for all public administrative datasets. They could usefully start when a project is new, such as here with students age 14+ in technical education.