An update on National Pupil Data

National Pupil Database / July 1, 2021

On January 29, 2021 the DfE published a written response to the ICO Audit [1] nearly one year on.

In April 2021 the Schools Minister committed in answer to a question from Daisy Cooper MP, to publish an update in June, including further details regarding the release mechanism of the full audit report.

Yesterday, on June 30th in answer to a chasing question the Schools Minister said, “A further update to the original publication detailing progress and the recommendations that have been successfully met will now be placed in the Libraries of both Houses on or before 22 July 2021.“

So, not June then. In fact, most likely on the last day Parliament sits before the summer recess. What interests us most now is to understand exactly what the audit findings and actions were in full, to identify those that have and have not been met, and what happens next as a result?

Why should we care, you might ask?

Isn’t the National Pupil Database data anonymous when the DfE gives it away? No, it is sensitive and identifying, personal confidential data.

The Department for Education has commercialised children’s school records, just like it planned to take your NHS medical records in the GP data grab earlier this year, postponed after over a million people opted out in just one month. The DfE started nearly ten years ago. The National Pupil Database is DfE’s “primary data resource about pupils” and “one of the richest data resources about education in the world” according to the Data Protection Impact Assessment first carried out in 2019, at that time holding over 21 million individuals’ named records.

The personal data, when released at pupil level from the National Pupil Database include children’s sensitive personal data such as Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND)and Free School (FSM) indicators. Name, date of birth, ethnicity and first language. Address details, attainment, absence, exclusions. Highly sensitive reasons for exclusion.

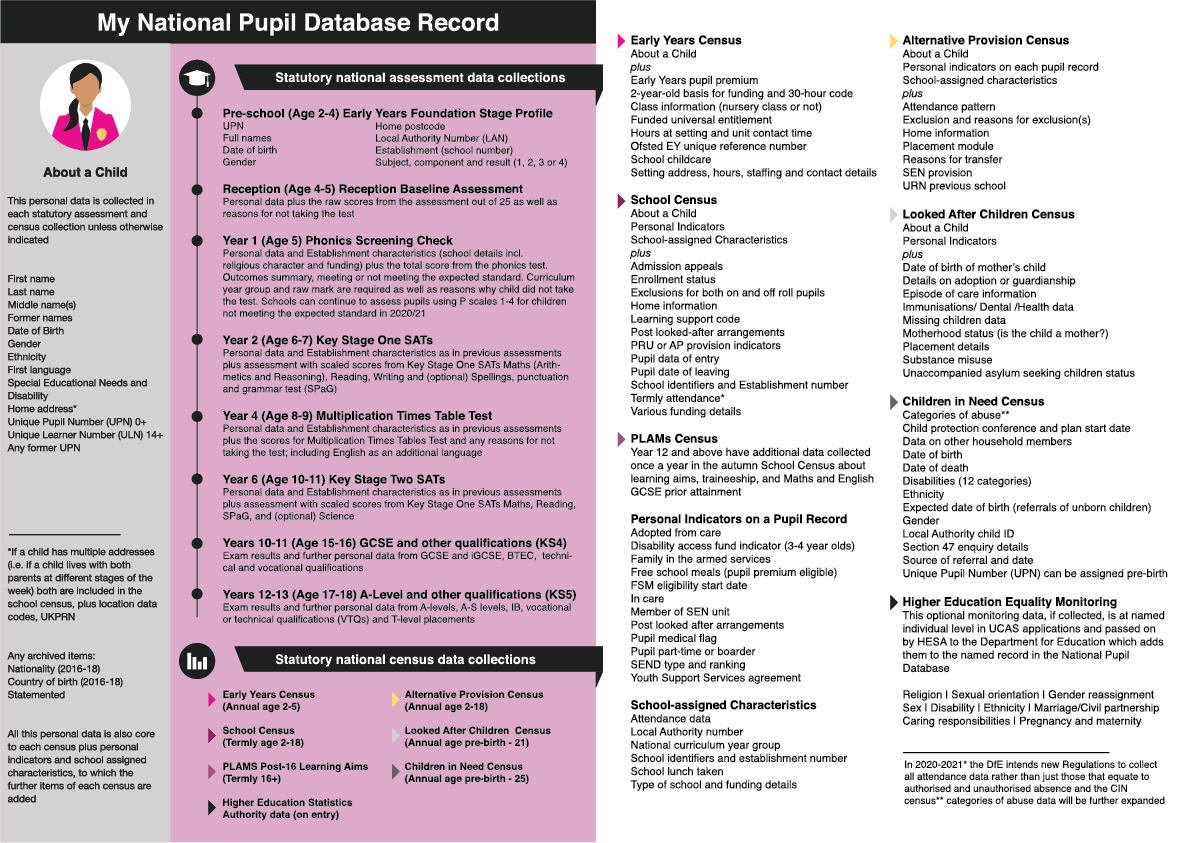

In summary: the 21 million plus named records (2019), growing by around 700,000 each year, are created from:

- Seven unique censuses collected about a child / family but without involving them. (Data are simply packaged as an admin task and submitted to the DfE, without families knowledge). In total, in an everyday state school child’s life age, that means 39 unique collections of the school census, plus any from the Early Years, and even more if you go into care, are a child in Alternative Provision or have Post-16 Learning Aims and go on to Higher Education, since UCAS data is added, including sexual orientation and religion, from equality monitoring from Higher Education applications.

PLUS

- The data items from every statutory test, from age 2-18 (Early Years Foundation Profile, Phonics, RBA, MTC, SATS, GCSE and A-Levels). Every statutory test is fed into the NPD, and linked to the child’s record.

The number of data items about each child are extensive in the National Pupil Database. The censuses (seven separate collections each year) have changed over time, many have been expanded while some items are no longer collected, since the collections began in 1996. Taking the “Spring census 2021” as a termly example, a total of 144 separate data fields would typically have been collected about each child in state education in January 2021. So around 400 data items each year. Multiple that by each year of their compulsory education. (Some of course are duplicates but are collected termly anyway). See Chapter 2.5 The National Pupil Database in our State of Data Report 2020 for more detail.

Who can access which data?

There are no really meaningful controls over which data can be disseminated to whom from the NPD, since the DfE created the law to be able to give it all away and goes beyond it.

After scrutiny and pressure, the DfE agreed not to give away nationality and country of birth while it was being collected in 2016. But it was nothing more than a verbal assurance in the House of Lords by Lord Nash. (We successfully campaigned to have it destroyed subsequently, in 2020).

It’s the same on Higher Education students’ religion and sexual orientation. We have been told they are not given away, but we don’t see the necessary safeguards around it and it’s why we have ten asks for change. The personal data from the Reception Baseline Test are the same. The DfE *says* they’ll not be given away like every other data once collected, but there’s no meaningful protections to prevent it.

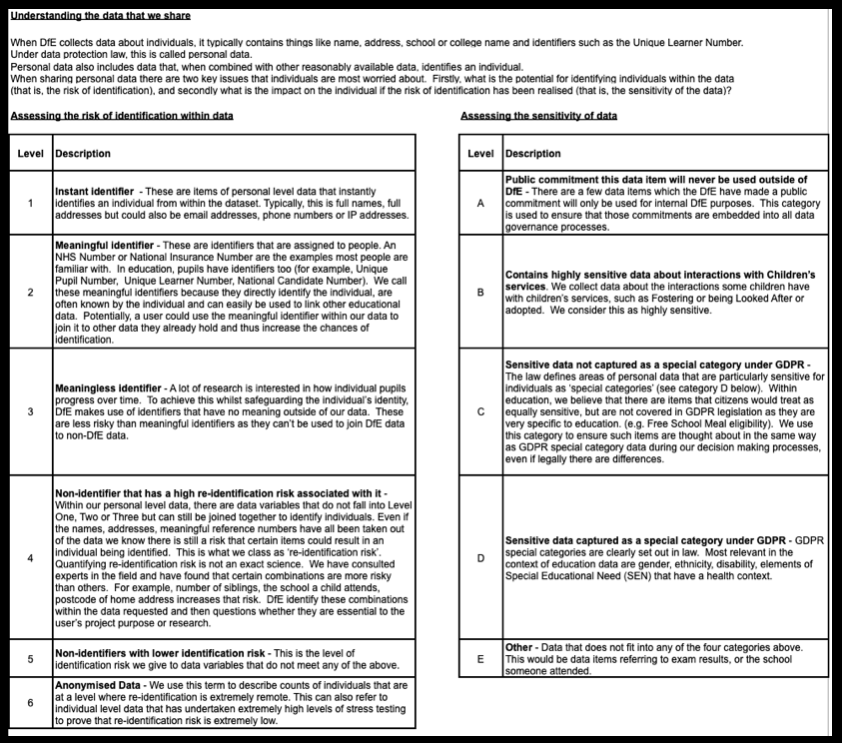

These are not statistics when released but identifying pupil-level data, and sometimes when given away even to journalists, “there was no suppression of small numbers“. The Department describes its risk of identification in six levels, and five of sensitivity.

Take a look at the end of this post for a set of applications and case studies where data goes. You can see a list of which data has gone where in the published Department for Education (DfE) approved data shares with external, third-party organisations. But last updated on 10 June 2021, there are now *ten* separate archived versions of this register, making it impossible to understand at a glance where data has gone since 2012. The releases have been tightened up a little since scrutiny began in 2015, but still too often the DfE circumvents the safe settings model introduced in 2018, in effect saying that if the criteria aren’t met for safe research use, ‘we’ll give it away anyway to the users we choose to approve’ anyway.

Prior to 2007, the Schools Census dataset was known as the Pupil Level Annual Schools Census (PLASC). Comprehensive PLASC data was first collected in 2002, including individual pupil names which government may have had ‘no interest in’ in as individuals in then, but fast forward 13 years later and the Home Office began using them to match with their own records. That is ongoing.

We are at a loss to understand why the ICO has not acted to enforce purpose limitation and stop this monthly data distribution full stop, and any distribution to any third party until the issues identified in the audit were fixed and the ICO has been assured the unlawful practice has stopped.

Sensitive data are given away excessively but no one knows exactly how much or which data have gone exactly where

In a presentation to the NPD User group in September 2016, the Director of the DfE Data Modernisation group acknowledged the excessive release of sensitive data: “People are accessing sensitive data, but only to then aggregate. The access to sensitive data is a means to an end to produce higher level findings.”

And the DfE 2018 Hive data dissemination discovery report found that, “Users are required to download the entire dataset, then remove and manipulate extraneous data reducing it to a specific subset. Many expressed a desire to be able to customise the data they downloaded.”

How much data are we talking about? In answer to a parliamentary question in 2018, the Schools Minister, Nick Gibb wrote:

“According to centrally held records at the time of writing, from August 2012 to 20 December 2017, 919 data shares containing sensitive, personal or confidential data at pupil level have been approved for release from the National Pupil Database. For the purpose of this answer, we have assumed the term sensitive, personal or confidential uses of information to be data shares classified as either Tier 1 or Tier 2 as set out in the National Pupil Database area on GOV.UK. [In addition] There were 95 data shares approved between March 2012 and this classification system being introduced.”

What is hidden by that 919 or the additional smaller number of 95, is that each of those 1,104 releases of data may have included millions of individual pupils’ and former pupils’ records. The Department does not publish data on how many records are released in each approved application. Since then, the number of releases as stated in the Department for education Third Party Requests register, had nearly doubled to just over 2,000 by our calculation in June 2020.

According to our internal analysis, since there is no official record published, of the documented requests for identifiable data that have been through the Data Management Advisory Panel (DMAP) request process in March 2012 – June 2020,

- 43% was released for research through universities

- 33% of the individual applications approved (as distinct from volume of data used) were for use by commercial companies and think tanks (note this is *separate* from additional releases via the ASP service).

- Around 14% of all applications approved were for other government and arms length bodies

- 6% go to charities and non-profit

- 3% exam boards

- 1% others make up the rest.

These numbers of releases of identifying and sensitive pupil level and data are distinct from volume of data used, i.e. they do not reflect the volume of pupil data going out to each requester. We cannot say there is more or less data used by commercial companies than universities for example, because it is possible that the 43% going to universities only get 1 million records in each release, whereas each commercial release is of the entire database of 21 million records, each for multiple years. We simply don’t know.

We believe that the DfE doesn’t even know itself. There is no transparency of the volume of how many children’s data have been given away in total in approved uses, because, “the Department does not maintain records of the number of children included in historic data extracts.”

There were 21 rejected applications between March 2012 and June 2020, including a request “by mistake” from the Ministry of Defence to target its messaging for recruitment marketing. These % calculations on number of requests exclude police and Home Office reuse, as well as contracted use through what was the ASP service, or Get information about schools (GIAS) service.

But the DfE do know the individual count of pupils’ data given to police and the DWP and Home Office as it is counted separately. In November 2019 a total 2,136 request for all pupils who attended a specified school during a four year period was provided to Merseyside police. It is unclear why police were using named pupil records from the Department for Education for criminal investigation rather than getting them directly from the school. The request was for pupils with a date of birth in the 4 year period 1992-1995 and those who attended the (same) specified school in the 4 year period 2006-2009. The data handed over for each individual in scope of the November 2019 request were name, date of birth, last known home address, entry date and leaving date.

And we know that between July 2015 and July 2020, 1545 pupils’ personal details were matched and handed over to the Home Office. Shockingly, neither Department can answer the question what happens to children or families as a result of this monthly collaboration. Caroline Lucas MP asked the Home Office about the interventions and their outcomes for children and families but both Departments declined to release this or even seemed to know. Chris Philp, Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Home Office replied, “The specific information you have requested is not readily available and could only be obtained at disproportionate cost.”

How did this happen and why?

David Cameron announced in 2011, the government would be “opening up access to anonymised data from the National Pupil Database […].” This was an expansion to other third parties, since academic public interest researchers already had access. The stated intention was that Open Data was going to be enabling, to allow parents to see how effective their school is at teaching high, average and low attaining pupils across a range of subjects, from January 2012.

In reality what happened was this. When Michael Gove was Secretary of State at the Department for Education, a law was changed to enable personal data from millions of pupils to be given away to commercial users. Not only did they start giving away the data of new pupils starting from the change of law in 2012, but started giving away the personal confidential data of everyone already in the database. Everyone who had been in state education since 1996, with named records starting from 2002. Anyone who was state educated, aged 42 and under today. The DfE in effect created a private sector marketplace from children’s public administrative data. The data were not Open Data. In fact it was briefly opened as such and had to be taken down. And the distributed data ever since, was labelled by the Department in different tiers of “sensitive and identifying” data.

The changes made in 2012-3 to the Education Act 1996 enabled the distribution of raw data from National Pupil Database under terms and conditions with third-parties who for the ‘purpose of promoting the education or well-being of children in England are conducting research or analysis, producing statistics, or providing information, advice or guidance‘, and who meet the Approved Persons criteria of the 2009 Prescribed Persons Act amended in 2012.

But those definitions have been pretty loosely interpreted. In fact, we believe they have not been met by giving data to journalists for example, because they are not ‘prescribed persons’. And even to academic researchers, more data was given away than needed, as we show above.

What you can do

No one expects the government to give children’s data away, so families don’t look for it either, and privacy notices while improved in 2017, still fail to deliver in their aims. In February 2018 we commissioned a poll through Survation who asked 1,004 parents of state-educated children age 5-18 about their understanding of data used in schools. 69% of parents asked, said they had not been informed the Department for Education may give away data from the National Pupil Database to third parties.

No one who left school since 2012 when the law was changed has been contacted to be informed of the news uses of their personal data in these ways that they would not expect simply from having gone to school. That’s every learner who was in school in the fourteen years between 1996 (when pupil level data began to be collected) and 2012 (when pupil level data began to be given away to the new third parties). It was impossible for them to know that the government started giving away their personal data in 2012 because the Department didn’t tell them. Schools can’t tell them today, because the children have already left.

Yet despite all this given away about you, there is no decent process for you to see your own national record. We’ve laid out the steps how you can do so, making a Subject Access Request here in step 3. Let us know how you get on. And write to your MP to tell them you want change.

The Education Act 1996 is no longer fit for purpose when it comes to education in the digital environment. Data protection law is permissive, to enable data sharing, and fails to adequately protect children and learners. It’s why we are calling for an Education and Digital Rights Act.

The Information Commissioner audit and found that the DfE are not fulfilling their duties that data “shall be processed lawfully, fairly and in a transparent manner,” yet the Department appears to want to carry on with business as usual. We think that is wrong. Our regulatory and legal challenge continues. You can help us here.

Editorial note: First posted on July 1, 2021. Layout edited July 5.

Other notes

- On October 7, 2020 the ICO published a summary of its findings after a compulsory audit of the Department for Education completed in February 2020 that had started after our legal team submitted a detailed case in June 2019 to the ICO. Liberty had also made complaints to the ICO and taken up a legal challenge of the misuse of pupil data for the purposes of the Hostile Environment.

- Briefing to download.

- Council of Europe Guidelines on Data Protection in Education Settings. [link]

- Samples of third party use from the Third Party Release Register created from information obtained through FOI