AI and Education: Existential threat or an everyday toolkit?

Events / July 18, 2023

On July 18th, in Committee Room 14 at the Houses of Parliament and with thanks to hosts Chi Onwurah MP and Lord Jim Knight, we held the event: AI and Education: Existential threat or an everyday toolkit?

Event objectives and what it was about

The aim was to create a room consensus of “the big picture” on AI and Education in devolved state education in England, the UK and beyond. A starting point of key issues and ideas to address (a) what is working well today (b) what is not (c) what is missing and (d) what is possible.

The event summary, a transcript for reference, and illustrated mapping of the discussion, can all be viewed and downloaded below.

We are very grateful to our lead contributors, Dr Wayne Holmes, Associate Professor in the UCL Knowledge Lab at University College London and member of The Council of Europe Working Group on AI and Education; Professor Prokar Dasgupta, of the RAI UK consortium; Mary Towers, specialist in AI and employment, at the TUC; Daniel Stone, NEU; Sonja Hall, NASUWT, 12 Ethical Principles for AI and Education; Julia Garvey, Deputy Director General, British Educational Suppliers Association (BESA); John Roberts, Product and Engineering Director, Oak Academy; Mark Martin MBE CITP teacher; Dr Janis Wong, Postdoctoral Research Associate on the Public Policy Programme at The Alan Turing Institute (AI literacy and children in Scotland); and Tracey Gyateng, Data, Tech & Black Communities (edTech research practice). Jen Persson of Defend Digital Me chaired the event.

We asked for “idea openers” from the lead contributors to get a handle on the wide range of issues on the table starting from the international and macro levels down through the areas of national UK policy and practice and industry point of view, through to teaching unions’ representatives and then to hear the voice of black communities from North West England and the views of children in Scotland on AI. We then welcomed contributions and questions from other attendees with the aim of moving forward views on what UK policy and practice should consider now, and going forwards in and around AI and education. We appreciated each and every one, well made and addressing other open issues and ideas.

Schools are sold AI in tools to support teaching and learning; and for classroom management. It’s used in biometric cashless payment systems; and even through apps and plaforms to infer and predict online risks, emotional states and mental health needs or suggest an interest in terrorism and extremism in AI-monitoring of digital classroom behaviour. The rapid recent growth in access to generative AI like ChatGPT and DALL-E has made questions more urgent over how schools manage plagiarism, copyright and authenticity. The hopes for what is possible remain high, not least for young people whose future society these decisions affect. But there is already pushback from students around the world using remote proctoring, or algorithms used in grading exams for example.

Going forwards we want to create a working summary of what would / should “good” look like across UK education; and what are the necessary steps and actions to take away in order to achieve it. If you were designing UK education policy for the next 15 years, what is key for you? Does AI feature at all, and if so, where?

You can read and download a transcript of the event here [note that this is a record for reference and should not be read as strictly verbatim] and read a summary here, below. We have done our best to reflect what was said but some of the words were hard to hear, especially during discussion and Q&A. Any errors or minor adjustments in transcription are 100% the fault of Defend Digital Me, not participants. This event was not live-streamed but voice-only was recorded only for transcription purposes. The Chatham House rule was applied to non-lead speakers.

You can also download our event handout that introduced the speakers before we started, so we did not have to.

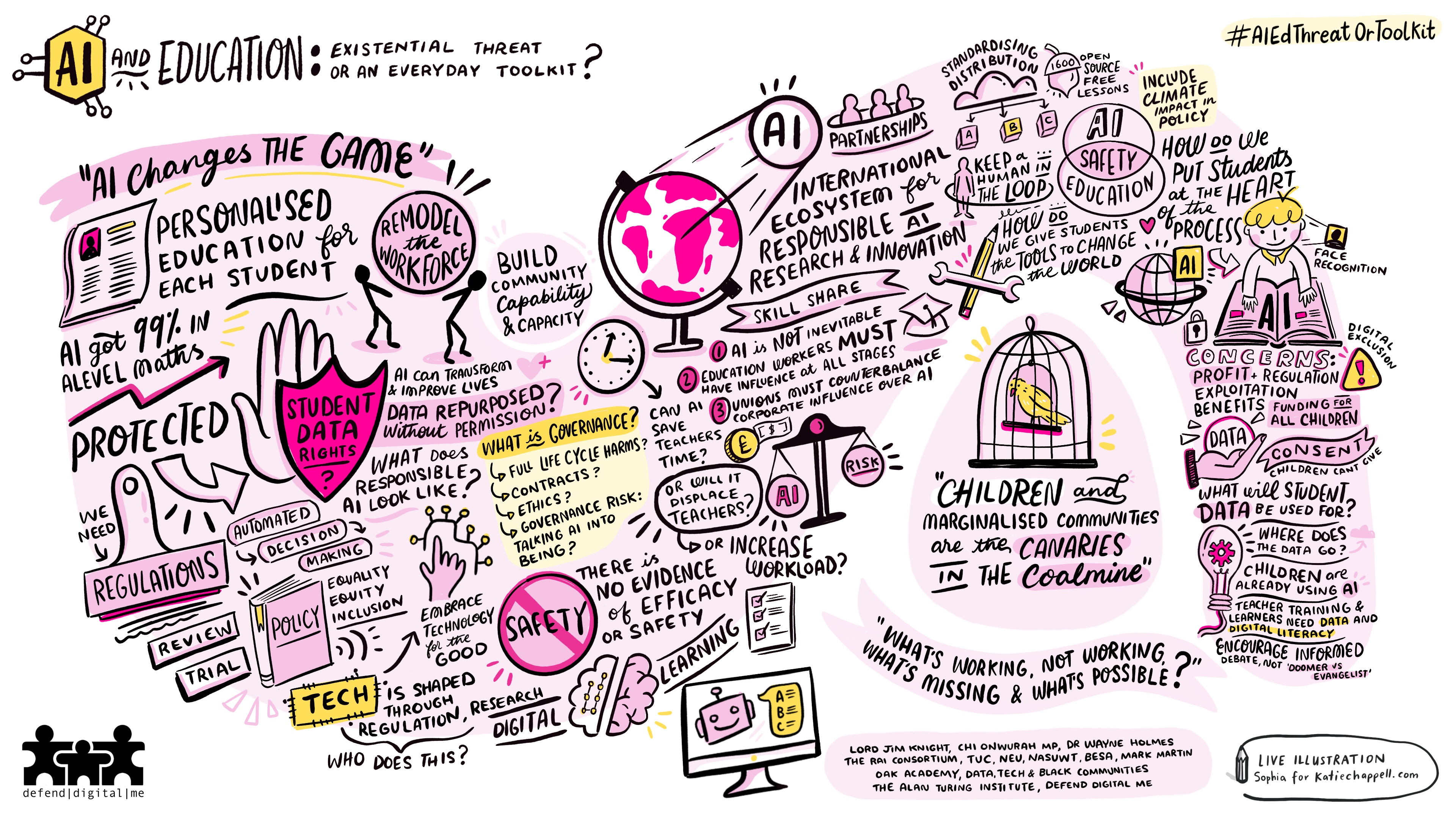

With thanks to Sophia for Katie Chappell Illustration we are delighted to share our illustrated mapping of selected key discussion topics and thoughts shared at the event. From the macro to the micro. You are welcome to download and share this artwork as long as it is with credit and a reference to the event as per its footer, and #AIEDThreatOrToolkit, for non commercial reuse and non-derivative purposes. CC BY-NC-ND.

Mapping #AIEDThreatOrToolkit. Credit: Sophia for Katie Chappell Illustration at the Defend Digital Me event #AIEDThreatOrToolkit July 18, 2023. CC BY-NC-ND.

Event summary in brief

“AI changes the game” started the evening. Hand-in-hand with the hopes that AI will be used to improve human flourishing, and access to equitable education and learning, the lack of independent evidence around what works and the outcomes for children was a continuous thread throughout the event. At the same time children should not be the ‘canaries in the coalmine’ for testing products or be used to build them, without any choice, simply because they attend state education.

School staff should not be left exposed to the risks of using of unproven products or be set up for failure if the tools are not properly introduced with training and ongoing professional development. The effects of AI on staff as workers and their labour rights need understood as much as affects on children and their digital labour in using products. Introducing tools to support teaching should be done ‘with’ and not ‘to’ teachers. Equally, the use of AI is not inevitable nor desirable in some applications, for example as teacher replacement.

What is AI at all and is there consensus on its definition? The curriculum needs to be re-assessed for how it promotes digital understanding, skills and citizenship for all. The challenges for schools and publishers from generative AI like ChatGPT and DALL-E are pressing, while the enforcement of regulation through data protection law has been slow to date. There is potential scope for creating access, while non-mandatory, to quality tested edTech products and platforms of all kinds through a national platform, some of which has been seen as possible as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. This should leave scope for teachers and school communities to choose what they procure and use.

How this might be affected by individual rights to refuse to be part of a training data set remains a hard problem, but one that we may be able to learn lessons from the US or Canada on. The real question is whether children should be used as training data, free digital labour for companies, whether in their use of edTech or the re-use of national pupil data. Is that in line with the aims of education? AI adoption must not only be ethical, but lawful.

Another overarching takeaway was that marginalised communities and children are often the first where emerging technologies are trialled and the emerging harms are experienced from the most intrusive products. AI Safety is an issue of the here and now in children’s lives in state education using high-risk products even if safety is framed more often as an existential or future threat.

Children’s lives are affected daily in ways that are not seen by parents through the use of tools in school that are designed to profile or affect or predict mood, mental health and behaviours. The proprietary tools are hard to see inside at all, beyond dashboards. The difference with why this matters in the consumer environment is that children in educational settings lack agency and autonomy, and cannot give or refuse consent where they have no choice but to be in the school environment subject to school procurement decisions, even if that means tools that might automate decisions that could be life changing to a child. Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education their child receives.

The definitions of safety, risk, regulation, and even AI itself all remain contested. Challenges remain in scrutiny of proprietary closed commercial systems with a lack of openness, user understanding, and measurable outcomes.

What could and should policy makers be doing for educational settings? Everyone seems to agree, even both the AI doomers and most ardent evangelists, that regulation is needed. But at the moment the same company CEOs calling for AI regulation more broadly, are also telling governments what that regulation should look like and crowding out what others feel more important and what enjoys a democratic mandate and public trust. What does that mean in practice for children’s rights and education? Most importantly, how do we ensure that technology and AI are not causing harm and are used in ways that support equitable access for children and learners to education and do not undermine human rights, democracy and the rule of law? What does the adoption of AI mean for the shaping of authority and power in education, of commercial access in shaping the delivery of education, and sovereignty over state school education systems? Where and why do we continue to use products in the UK recognised as high risk for students or banned elsewhere in the world?

Parents and children’s rights as set out in law, need to be (a) understood and explained in school settings and (b) possible to exercise. School staff need to know that the tools they introduce are safety and quality controlled, suitable for use in their classrooms and worth investing budget in. Parents and children need better information and understanding of AI and tools used inside and outside the classroom. Products must be proven and open to independent public scrutiny before being allowed to affect millions of children’s lives paid for by public money. Legal questions around current practice and lawful practice when it comes to using children as training data, need addressed. The ‘think big’ questions include if and how AI and the companies behind their tools, are redefining the values, nature and delivery of the education system. And if a platform or product(s) could and should be developed in the public interest that is also in the best interests of every child. Above all, the educational outcomes for children using them must be better than using the alternatives to make their case. All of that, needs infrastructure and systems support and direction from policy makers.