School pupils’ ‘sex survey’ data offered to researchers: Opt out fails children on reuse of ID and Local Authorities’ survey

news / February 5, 2025

February 5, 2025: A new development in this ongoing saga for families in Scotland and a case study in why a national ID, an “opt out” model, and big data gathering by the Scottish government via Local Authorities and schools, have failed children and their right to privacy with lasting effects.

Shockingly, adults who want the data use and access, appear to blame the children for not opting out or skipping the questions they didn’t want to answer. The BBC today has reported, “School pupils ‘sex survey’ data offered to researchers“.

In Scotland, parents are furious that data from the most sensitive and intrusive personal questions including some about detailed sexual behaviours and abuse, from a survey of pupils in state schools, are now being offered unexpectedly to researchers. In 2021-22 the Health and Wellbeing Census took place in schools across Scottish local authorities, retaining the children’s unique school identifier number. Sixteen of 32 withdrew from the process, 12 due to concerns. In December 2021 the Scottish government overruled the Scottish Children’s Commissioner’s request to pause the survey. Data protection law offered no protection at all, and there is no route for recourse or remedy.

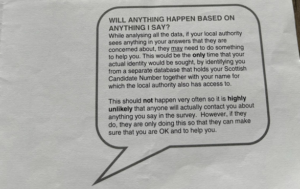

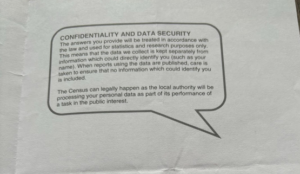

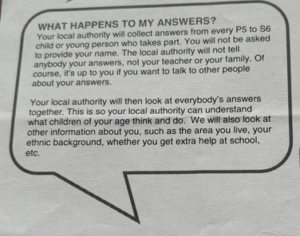

Now the data’s use and access is going beyond what parents (and children) understood at the time of collection. The government is also quoted as insisting the census was ‘confidential and voluntary’, which is a stretch of the words, since the personal confidential data was accessible and identifiable to Local Authorities at child level, before being passed on to the Scottish government to be retained, which was not made very clear to children taking part, or their parents who were even refused sight of the blank questions.

It really was all as outrageous as it sounds, and it’s far from over.

It is an important example of some of the key issues in current connected Bills and policy discussion in Parliament:

1. The Data Use and Access Bill (the stretch of research ‘consent’ Article 68, and in 77 taking away the duty to tell people about it, and this all moves the goalposts of what data protection changes are going to mean for data already held, both need meaningful safeguards added);

2. The Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill (unsafe Local Authority to Government data handling and transfers, and reusing a national (Scottish) pupil ID out of context. For this CWBS Bill the ID must be named before more Bill debate for meaningful scrutiny and an amendment to safeguard from HomeEd data transfers at named / identifiable level to the DfE)

3. Copyright and AI. (Opt out does not work, people want opt in, pending the consultation closing February 25th). (No opt out is even offered of the distribution and third party access to the national pupil database and reuses of school census data from every pupil in England).

Key takeaways

- Opt out fails children on reuse of any unique ID and Local Authorities’ held data. While better than nothing, families and children want opt-in.

- Consent should not be stretched to new reuses beyond what people expected.

- Even public interest research does not enjoy unqualified public support when it comes to reuse of personal confidential data about us.

- The public want to remain in control of their rights around onward data distribution and be able to opt in, not rely on opt out, to exercise meaningful rights.

- Families, children, learners otherwise not-in-school to be on the additional Local Authority registers planned as well as everyone else in state education, really need an independent Ombudsman for disputes that knows education as well as data, and to have a route for redress and remedy that does not exist today for children when it comes to data matters.

- In Scotland, the ICO and data protection law have not protected their rights, and parents feel let down by state institutions involved.

- The Data Use and Access Bill should not move the goalposts on what people were told in the past, and should only be applicable to data collected or processed for the first time under the new law. None of the provisions that reduce protections should apply to data already processed under prior data protection law.

The DfE and DSIT public engagement work published in August 2024, Research on public attitudes towards the use of AI in education, sums up what parents’ and children want in the UK. To take back control of data about them. Not to cede control to researchers, to the State, or to companies. Data re-use must be opt in across all these policies and legislation running in parallel, all of which undermine children’s agency and reduce their protection when it comes to who knows what about them.

*Bill article number corrected to 68 on 5/2/2025

More in depth background

Data Use and Access Bill

(a) Such research as in Scotland, will no doubt be argued to be qualifying scientific research that can use the exception for data reuse in the public interest (DUA Bill Clause 68).

Parents in Scotland want these data from their children destroyed, not kept in perpetuity and potentially now re-used for projects they do not agree with, or for processing at scale, by or even for AI development and any other purposes which the new stretched “consent” basis in the DUA Bill article 68 allows. It is not fair for adults, and even less so for children in particular who may not have consented directly at all, where consent was assumed and ‘given’ by their parent.

Article 68 really is pushing the boundaries of what is permissible and ethical.

Furthermore, on this Bill, (b) it is also why the very last point raised in Report Stage debate on the DUA Bill is so crucial about its applicability to data already held on commencement date matters. Scope creep undermines public trust in all research and all data collection. If new data protection law can simply wipe out what was valid before it, and makes conditions less protective of data held than people were told to expect, then everything people understood before is no longer trustworthy, and any decisions like opt out / consent are no longer valid, because the government has moved the goalposts.

Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill

The CWS Bill Human Rights Memorandum* suggests (p10) the DfE claims that data protection law* will offer a safeguard to the protection of EHE (Home Ed) children’s data that the Bill seeks to permit to be processed by not only local authorities more widely, but by the Secretary of State at child-level. The Bill mandates that often the processing of a child’s records to be collected in vast and unlimited detail (436C) and wide distribution including extraction to the national Department for Education (Clause 25, 436F) must be attached to an as-yet undefined national ID number or “single unique identifier” (Clause 4).

The Memorandum* claims that interference with the right to privacy will be justifiable, necessary and proportionate. How can this be anything but a guess if what the ID is to be, is still secret? Data protection law has offered no protection at all in this case of the Scottish survey, the ICO has not supported children’s rights and what families want, and there is no route for recourse or remedy. The same is true of this Bill so far.

“One of the biggest concerns raised at the time of the survey was that it included pupils’ individual candidate numbers – through which children could potentially be identified.”

Stringent safeguards must be applied to any consistent identifier for children, but in this Bill it’s shockingly not even yet been defined what the identifier will be, only that it must be used. And it’s already been through the House of Commons closest scrutiny stages. There has been no scrutiny at all of the costs, risks and benefits, unintended consequences or potential for harms of the ID the Bill makes compulsory to re-use. Peers debated similar problems in the Schools Bill in 2022 at length, so why are they back largely unchanged?

The Bill could instead mandate that persistent identifiers should lapse routinely where used in a new context when the conditions necessitating their use or conditional state of being data “of a child” or “EHE” are no longer met, as set out in existing DfE UPN guidance. And that persistent child identifiers should lapse when the individual is no longer a child or after age 25 for care leavers or those with disabilities (age in line with EHCP / SEND practice). Importantly, the DfE’s UPN in England must be a ‘blind number’ not an automatic adjunct to a pupil’s name. How will these duties be met in widely distributed use of the new as yet undefined ‘single unique identifier’ SUI demanded in the Bill? A comparison must be published of why the features of the UPN Guidance (2.3 Data protection responsibilities for local authorities and schools) are not going to be similarly applied to children’s other unique identifiers and comparison with the new plans once they materialise. This cannot be allowed to pass as it is, without scrutiny about an ID ‘as yet unknown’.

A lesson to learn: Parents in Scotland did not expect the questions asked under the 2021-22 survey title of “wellbeing” to be as intrusive and personal as they were, and the same weakness is found in the current Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill where ‘safeguarding’ and ‘welfare’ seem often conflated with ‘child protection,’ and ‘wellbeing’ with ‘health’. These terms have important meanings to professionals and often in law, and their use demands accuracy, which the Bill could do with tightening up too.

On the Copyright and AI consultation

This is also a good case study to demonstrate that opt out is insufficient protection in any data, or connected in AI and copyright debates, which are not about copyright for children per se despite the consultation closing on February 25, but about working around current protections in law by changing it, to enable other people to exploit children’s data and content, that is not allowed today, and as public engagement shows, is not what the majority of the public wants.

“Trust in tech companies was extremely limited and there was little to no support for them to be granted control over AI and pupil work and data use. “

“Profit was almost universally assumed to be the primary or sole motivation of tech companies, rather than the desire to improve education and pupil outcomes. Reflecting starting views of tech companies as non-transparent and assumptions that data is sold on to third parties, participants did not trust them to protect or use data responsibly. Parents and pupils assumed that given free rein and with no oversight, tech companies would choose to sell data on to other companies with little concern for pupil privacy or wellbeing.”

“There was widespread consensus that work and data should not be used without parents’ and/or pupils’ explicit agreement.”

Background on page 9. (3.3) of our older DUA Bill briefing https://defenddigitalme.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/DUA-Bill-Second-Reading-2024-Briefing-v2.0.pdf

Extracts from the pupil information given out in Scotland in the 2021-22 Health and Wellbeing Census, which was not clear it would be sent to be kept in national records and reused.