Counting children outside schools in national records

Blog news / April 8, 2022

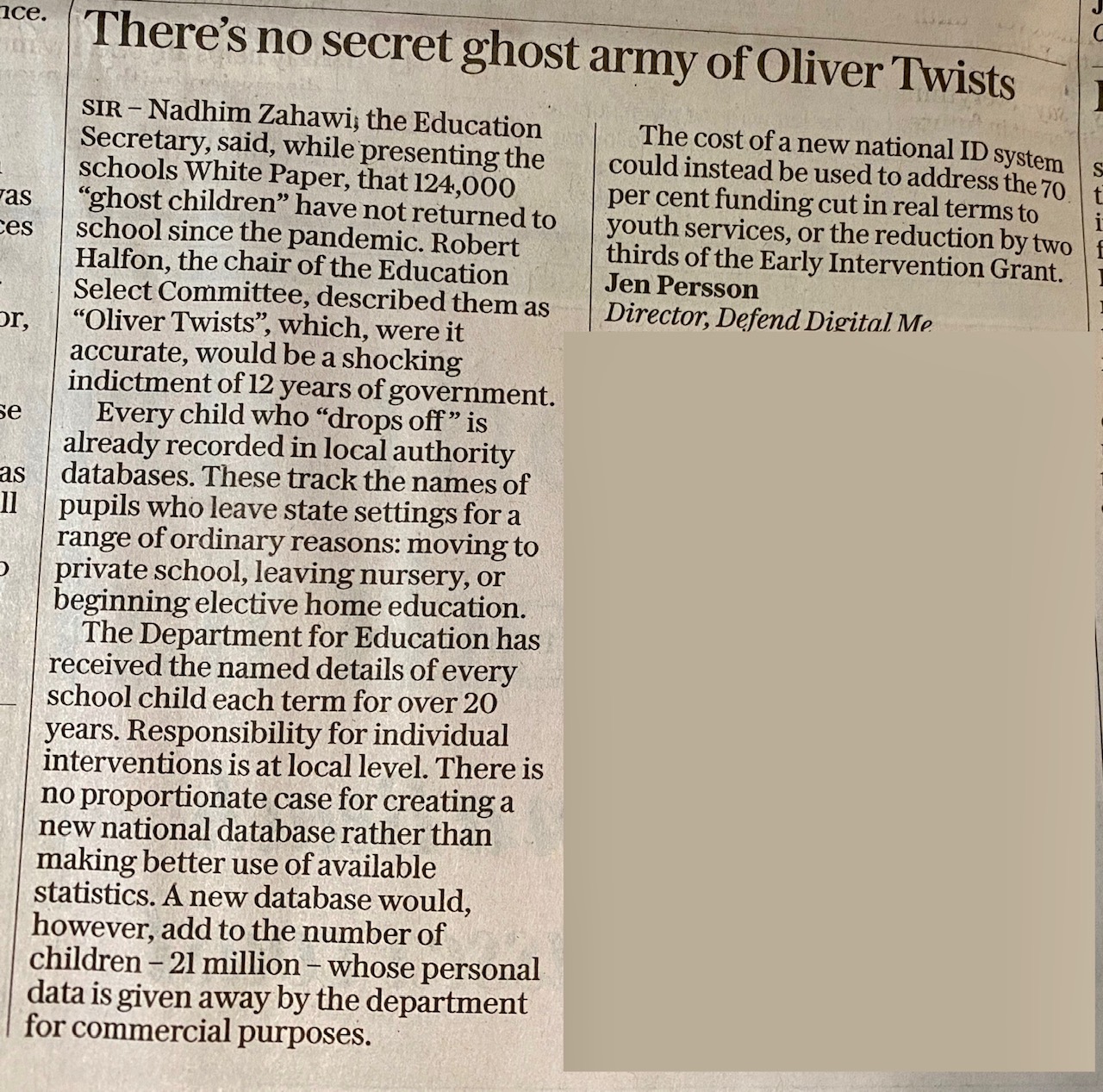

The Telegraph published an edited version of our letter to the Editor on March 30, under their sub-heading, There’s no secret ghost army of Oliver Twists.

We wanted to draw attention to the concern we have with

- (a) the recent accuracy of debate around counting children who are out of school used by the Department for Education and its arms length bodies;

- (b) the conflation of different characteristics of children out of school for different reasons that creates misleading numbers and associated inferences; and

- (c) the related proposals for the collection of more children’s data in a new national database in order “to find them all”.

We have been carrying out our own research with Local Authorities to better understand these questions since mid 2021 and will publish it when it is complete. In the mean time, this is a long read for reference, to clarify how the government is already counting children outside schools in England.

Pupil numbers being used by the Department for Education and its arms length bodies

The Secretary of State for Education *and* the Chair of the Select Committee suggested in Parliament during the Schools White Paper debate, on March 29th, that 124,000 children are out of education and have not returned to schools as a result of the pandemic.

Mr Halfon did it again in TES this week. This misinformation is harmful.

Full Fact already pointed out that Robert Halfon was wrong in July 2021 to claim 100,000 “ghost children” have disappeared from school since the start of the pandemic.

Full Fact suggested that the number appears “based on a report produced by the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ), which states that during September to December 2020, 93,514 pupils in England were severely absent.” However, the idea that these children have failed to “return” after the pandemic is problematic because it suggests that this number of children was regularly attending school before the pandemic, which is not the case.

“In the autumn term of 2019, i.e pre-Covid 60,244 pupils were labeled as severely absent.”

These children are known, and counted, and are not ‘children missing education’. They are not “ghost children”.

This important subject needs a better standard of informed debate.

Children not-on-a-school-roll should not be conflated with absence figures, children on the school roll but not in-school

This whole topic area conflates 4 main groupings of children, even within which children are not homogenous. (1) Those children registered at school who are persistently absent, (2) those children who are known but not counted on a school roll or national register, for whom there are many different reasons they might be counted as not-on-a-school-roll, including home educated children (“EHE”), who quite correctly may never have been on a roll in the first place. (3) Then there are children labelled as missing education (“CME”); and lastly, (4) children who are not known or counted anywhere, those considered “off the radar” with additional inference of being ‘at risk’. These should be explained very separately when talking about counting children out of school, and should not be conflated.

Persistent absence

Historically, the main driver for absence is illness. In 2020/21, this was 2.1% across the full year. This is a reduction on the rates seen before the pandemic (2.5% in 2018/19).

A pupil on-roll is identified as a persistent absentee if they miss 10% or more of their possible sessions (one school day has two sessions, morning and afternoon.) 1.1% of pupil enrolments missed 50% or more of their possible sessions in 2020/21. Children with additional educational and health needs or disability, have unsurprisingly, higher rates of absence. During Covid, the absence rate for pupils with an EHC plan was 13.1% across 2020/21.

“Authorised other reasons has risen to 0.9% from 0.3%, reflecting that vulnerable children were prioritised to continue attending school but where parents did not want their child to attend, schools were expected to authorise the absence.” (DfE data, academic year 2020/21)

There is government Statutory Guidance called “Ensuring a good education for children who cannot attend school because of health needs” (Published in May 2013).

There are further important caveats to remember when talking about absence data comparisons over time. The persistent absence threshold has consistently been made easier to reach since 2010, moving from 20% in 2010, to 15% until 2014/15 and only 10% since 2016. So a child is classified as “persistently absent” much more quickly today than ten years ago. Furthermore, the legal structures of educational establishments change it changes how data is counted and when.

It’s also worthing noting that data are inconsistent over time in another way too. The 2019 Guide to Absence Statistics draws attention to the fact that, “Year on year comparisons of local authority data may be affected by schools converting to academies.” While some government work may remove excessively high numbers, due to the double counting, others may not be aware of these data issues and give misleadingly high figures.

Home educated children (“EHE”)

Children have the right to education. Part of that right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is a general principle that a child will be educated in accordance with their parents’ wishes.

Protocol 2 Article 1 of European Convention on Human Rights (this Article is incorporated into national law by the Human Rights Act 1998) states,“No person shall be denied the right to education. In the exercise of any functions which it assumes in relation to education and to teaching, the State shall respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching in conformity with their own religious and philosophical convictions.”

And parents, carers (people of legal guardianship), have the duty to ensure a child of compulsory age receives a suitable education. In England a child is of age at the beginning of the 1st term after their 5th birthday, and a child remains of compulsory age until the last Friday in June in the school year that they turn 16, and must then remain in education or training until their 18th birthday.

Home education doesn’t mean only learning in the home, but may include a variety of learning environments, including private educational settings but excluding what people generally call independent or private schools. Many children within the EHE label, may be attending Ofsted regulated settings that don’t fall under the definition of a school. So the ‘elective home education’ label means a child is receiving a suitable education but in everyday terms is not considered “state educated” or “at private school”. While people might talk about these children being in an alternative setting to regular state education, it’s not what the term Alternative Provision means.

Children in Alternative Provision (“AP”) is not be confused with counting children in alternatives to state education

The DfE describes AP settings are places that provide education for children who can’t go to a mainstream school. We would argue this is of itself mislabelling, as they may be able, but may have been told not to. AP guidance covers the use of settings that are still considered state education, where:

- local authorities arrange education for pupils who, because of exclusion, illness or other reasons, would not otherwise receive suitable education

- schools arrange education for pupils on a fixed-period exclusion

- schools arrange education for pupils to improve their behaviour off-site

These children are counted by Local Authorities and the named records are sent to the DfE once a year in the Spring Term. The AP census includes pupils attending a school not maintained by a local authority for whom the authority is paying full tuition fees, or educated otherwise than in schools and pupil referral units, under arrangements made (and funded) by the authority. The introduction of the dedicated schools grant requires that accountability for expenditure in this area be demonstrated, since the place is funded through the dedicated schools grant by way of the high needs block, and not via the school census per-pupil registration.

Broadly speaking, for the purposes of this census, ‘alternative provision’ includes the following settings when state funded (more details p8-10) and may be of varying hours:

- independent school

- hospital

- non-maintained special school

- not a school

- further education college

- one on one tuition

- other unregistered provider

- work based placement

Children missing education (“CME”) is separate and different again

Both the numbers on a school roll but absent and those never on a school roll and receiving ‘suitable education’, should never be conflated with children missing education. (“CME”). Our Local Authority research suggests there is conflation and confusion on who counts what, when. And counts over a year may fail to remove children from double counting that were one for say the first 6 months of the year, and are in the other category at the end of it.

Knowing this number of ‘children missing education’ is already a legal obligation on Local Authorities in s436A of the Education Act 1996. A call for a new, especially any national database to record these children is misguided in its duplication.

There is government Statutory Guidance called Children Missing Education (2016), which states that children of compulsory school age who are not receiving a suitable education should be returned to full time education either at school or in alternative provision.

The Government may not collect national pupil-level data on the number of children missing education, but this does not mean no one collects those numbers nor does it mean the scale of the problem is completely unknown. It is certainly not 100,000 “ghost children.”

All schools (including academies and independent schools) must notify their local authority when they are about to remove a pupil’s name from the school admission register under any of the fifteen grounds listed in Regulation 8(1) a-n of the Education (Pupil Registration) (England) Regulations 2006.

In 2011, TES asked Local Authorities, added it up and counted 11,911 children as Children Missing Education. In 2014, the NCB made an unweighted estimate of 14,800 based on a sample of just around half of the Local Authorities in England. Our own count and research is ongoing.

There is clearly a problem with inaccurate use of the CME designation. It seems not only to be a problem of numerical consistency and statistical practice, but policy applied to children’s lives at Local Authority level. We can see from our research that there are wide discrepancies in counting what, and there is no clear decision making of how some children known to be receiving elective home education, but where the standard is not known, are arbitrarily moved from EHE into the CME category.

Part of the Department’s problem counting accurately, is that their counts of ‘pupils’ are primarily based on their accountability for money, not counting children. There’s confusion between counts of actual numbers, versus the use of full-time-equivalent numbers.

These questions will not be solved by creating yet another database for miscounting.

As we wrote to the Children’s Commissioner in January 2022,

“[It] might be better to prioritise the standardisation of the quality of the existing and extensive Local Authority data on CME and other data held. When we researched the expansion of the [separate] Alternative Provision (“AP”) Census in 2018, when the DfE added sensitive ‘reasons for exclusion’ to the transfer records without informing families, we found that Local Authorities had inconsistent ways to count children; (a) a headcount of those in AP on the day of the census, (b) a total headcount of those ever in AP in the 365 days previous, (c) the number of hours spent on total AP funding calculated as a Full Time Equivalent (FTE) which could be significantly lower than the actual headcount (eg 18 children each spending one hour in AP a week may have been only counted as if ‘one’ child in total.)”

Our research suggests that not all CME children actually share the same definition at LA level, but no one seems to want to tackle the disaggregation. For example to remove those children outside state education, in Elective Home Education, for whom the local authority has no safeguarding concerns.

There is government Statutory Guidance called Working Together to Safeguard Children (2016).

Local Authorities appear to have no consistent process for children they know are getting an education, so categorising them as CME is inaccurate. There is no obligation to assess children who are home educated other than for the LA to have no safeguarding concerns, and that the level of education is ‘suitable’. It could have significant consequences for policy making in terms of resource allocation, and most concerningly for the child’s private and family life if their information is ‘forwarded on’ to other services and they start to be automatically categorised by computers, “if CME then XYZ”.

Children “on the radar” but whereabouts unknown in the system

After children are labelled as CME there is a further disaggregation that is not made. The 2014 NCB report, “Not present, what future?” estimated based on FOI from 45 Local Authorities that 1,022 of CME children, were “off the radar” and from this extrapolated that nationally it could be up to 3,000 children at any one time. These children are known and were counted, known to be missing education, and in addition have become of unknown whereabouts. This arguably should be one focus of current work to find those known ‘needles’ in the haystack, rather than adding more hay.

Children “off the radar” and were never known to the system

The Children’s Commissioner and MPs may have concerns that there is a number of children not in education and not counted anywhere ever, but if so, they never clarify this within the number they refer to. Often they create a misleading inference is that this is over 100K, when in fact there is no evidence for the number of children unknown to any part of ‘the system’ that have never been known to exist at all. No database requirement will change that and make families register who have not. Any number here is a guess.

There is a raft of various proposals going on to increase child data surveillance

The Children’s Commissioner for England, Dame Rachel de Souza’s idea is to create a single national identifier, and to link pupil records with police and NHS numbers. She announced it last August 2021 behind the paywalled Telegraph, and again in January in the press, and more recently on March 2022 on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme.

Here again, she had difficulty getting the numbers right, with broad repercussions.

As Full Fact explained in February, “this BBC article, published in January, claims that “between 80,000 and 100,000 children [are] not on any school rolls at all” following national Covid-19 lockdowns. This is not accurate.

The article attributes this figure to the Children’s Commissioner for England, Dame Rachel de Souza, after she made the claim on Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour on 19 January, but her office later told us she “misspoke in the midst of a long, live, on air interview”.”

Full Fact’s view is that, “the Children’s Commissioner misspoke when she made this claim. There is no current data to support this.”

As we wrote to the Telegraph Editor this week, every child who “drops off the school roll” today is known to Local Authorities and already recorded in Local Authority databases. These track the names of children who leave state settings for a wide range of ordinary reasons and does not mean they are “ghost children” or are all “on the streets” as Mr Halfon described it in Parliament; the numbers for children not on a school roll can include those moving to private school, leaving nursery, or for elective home education. The Local Authorities and Department for Education (“DfE”) can access those statistics already.

The Children’s Commissioner call for a new database here for such children is not needed. They’re already on several.

In follow up, we wrote to the Children’s Commissioner and suggested she might want to reconsider the proposals of one-ID-to-rule-them-all. We look forward to a response. And we’re far from alone among experienced organisations that believe giving every baby a new national ID number is a bad idea and who share concerns about the accuracy of debate in this area.

The DfE has received the named details termly of every schoolchild (recorded on and off roll) for over twenty years, in the School Census, and Alternative Provision (“AP”) Census and Children in Need (“CIN”) census and more, including Service Families, and Youth Offending. We suggest that additional named data is neither necessary nor proportionate at national level, over statistics.

If the data are required as statistics or for scientific research purposes then they should be collected as statistics.

Aside from the lack of necessity for named data at national level, at the practical level datasets are not easily interoperable or desirable to link when not designed for purpose and without due consideration for historic standards, and the ongoing daily demands it creates for data cleansing, governance, audit and oversight. It’s idiotic to collect the same data in multiple places with increased risk of errors, multiple counts of the same person in cumulative work, and cost.

To date no case has been made for a duplicate, national named database of children not on the school roll and there is demonstrably poor understanding of those that already exist.

What are unique pupil identifiers?

Debate not only demands informed, accurate use of facts and figures, but also requires a good understanding about the law and practice on the existing ID numbers children have today.

The DfE requires children to have more than one unique identifier within a childhood of state education. Unique Learner Numbers (“ULNs”) are mandatory for all pupils on roll aged 14+ on census day and for pupils no longer on roll who were aged 14 on their leaving date. ULNs are assigned to pupils aged 14 or over in publicly funded education and training.

The Unique Pupil Number (“UPN”) use is even wider. It is allocated to every child in school, as well as any child considered at-risk even pre-birth. If an unborn child on the at-risk register dies, they are counted in the Children in Need census, and the DfE gets the details.

Maintained nursery schools can allocate UPNs, so children may routinely have a UPN from the age of 2 or 3 years onwards. It is already widely used across Local Authority and DfE databases. It is however, supposed to be “a blind number and not an automatic adjunct to a child’s name“. It must not be used for any other purpose outside education. The DfE’s own guidance states, “the UPN must lapse when pupils leave state funded schooling, at the age of sixteen or older.” We wonder if in fact the DfE respects this, given the problems identified in the the ICO audit around the Department’s retention policy? We are still working towards its full release to find out.

These are *highly sensitive* data, such as detailed categories of abuse. In fact, data so sensitive, we would argue they should not be collected as they are today on a named basis at national level at all. Instead the DfE should only have statistics about children who are the subject of a child protection plan, in local authority care, or unborn children who will potentially need support from social care services.

“the Department [for Education] can track and analyse the journeys of individual children and explore how these vary according to their characteristics and needs.” (page 15, CIN census guidance)

Despite this individual level ‘track and analysis’ capability, figures obtained by the charity Article 39 show that twenty-two children aged 16 and 17 died while living in [state] supported accommodation between 2018 and 2020.

The purposes of another national, named data collection for millions of children with a unique identifier, especially at named, detailed level, are unclear.

Data rights are children’s rights too

The children and young people don’t even know these records exist about them today. But they should and they have a right in law to know. The DfE is yet to create the mechanism for children to know they have national records, in over 20 years of collecting their named data.

Our survey of parents in 2018 showed not only did parents not know the National Pupil Database existed, but they didn’t know records could be linked with other datasets or given away. The key issue about linking records from education with anywhere else, but especially with police, is one of a child’s best interests and question of trust. If you breach a child’s trust in one public authority, it will be harmed across them all. They may not only fall out of education, but avoid seeking health care or any confidential services to avoid the potential for police involvement. “A common identifier for children” is neither a realistic nor a desirable method to address the best interests of the children. In fact, it would be counterproductive, driving those individuals even further from the oversight of the State.

The DfE has a poor record of managing the millions of learner records it holds, including enabling access by gambling companies. In 2016 Ministers did not tell the public that the new nationality data to be collected in the school census was to be handed over to the Home Office to further the aims of the Hostile Environment. Monthly handovers of pupil data continue. The idea that the Children’s Commissioner wants these data to enable an unidentified, unlimited number of persons in an unstated number of organisations, to be able to, “look and see who is in school now” in real-time, without oversight or safeguards is troubling, in particular while the Hostile Environment handovers for purposes of immigration enforcement continue, and neither the DfE nor the Home Office appears to care enough to know or has any public accountability for what happens to families as a result of the data processing.

If the recent ICO audit is ever published in full, including findings on commercial reuse of identifying, sensitive and confidential national pupil data introduced in 2012, we might see if the DfE has improved or is still inadequate. But to demand “more data” is mistaken and will further undermine public trust in the Department and their data handling.

What happens now

The first project in this somewhat mistaken slew of ideas is already underway, with a national contract won by Wonde, the collection by the DfE of absence / attendance data at individual pupil level for potentially the ful cohort over 8 million children currently in educational settings each day. The DfE intends to keep the data for 66 years.

There is clearly no intention to inform families or the children the personal data are from or provide them with any right to object or to restrict processing. Existing privacy notices neither reach families nor cover this new daily process. We are very concerned for children’s rights given that the combination of more automated data collection, no safeguards on fair processing, and the possibility to direct data to any third party is all done without oversight of school staff and no involvement from families.

There is neither strict necessity nor proportionality for the DfE or Children’s Commissioner to have this personal data at this level. This is not only a new data collection (daily, in real time) but is intended as a precursor to “our ambition to introduce more automated data collection in the future.” This is not the same as, and separate from, COVID emergency measures to track COVID pupil attendance numbers as statistics, but routine daily pupil-level and attendance data.

The UK ICO has previously described necessity as, “It is not enough to argue that processing is necessary because you have chosen to operate your business in a particular way… not whether it is a necessary part of your chosen methods.” Limiting the fundamental right to the protection of personal data, must be strictly necessary. Not just because you want it. More specifically, proportionality requires that advantages due to limiting the right are not outweighed by the disadvantages to exercise the right. In other words, the limitation on the right must be justified even before looking beyond data protection law, to high standards of not being able to do the same thing in another less intrusive way.

The DfE says 87.4% of pupils are attending. It is unclear what the necessary purposes are of this new national data collection for each and every named child, not statistics (8,422,521 children in state educational settings) every day. The responsibility for individual interventions remains at school setting or Local Authority level. There is no national statutory individual child level duty at the DfE or Children’s Commissioner. There is no publicly communicated purposes how or why data will be processed daily at national level for every child attending state educational settings in England, or on roll, when DfE’s own data says nearly 90% are in school.

A common child identifier

Separately, Lord Kamall suggested an addition to the Health and Care Bill and on March 3, 2022 said in debate that a report: “will cover improved information sharing between all safeguarding partners, including the NHS, local authorities and the police, as well as education settings,” and that the Department for Education has already started its work, “which will look at the feasibility of a common child identifier.”

Our work with the College of Policing and Home Office informs our belief that the national police computer systems (PNC and PND and future LEDS) are not fit for purpose to support interoperable unique IDs for children either. And the NHS number, like the UPN has protections in law as a national identifier.

A common child identifier quickly grows into a common adult identifier. The DfE track record to date, suggests they do not have the capability to handle a national ID number safely or transparently. There will be strong opposition. We would strongly advise against it.

What should be happening

Before these costly digital drives go ahead, there should be open consultation with a wide range of stakeholders.

In 2018 on the 30th anniversary of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, as Children and Families Minister, Nadim Zahawi reaffirmed the UK commitment to give due consideration to the UNCRC when making policy and legislation. Despite this, there is no visible intention or routes to realise protection of those rights in today’s policy or practice, in particular around children’s data rights. Demands for “more data” will not uphold any child’s rights, will distract needed resources, and will likely fail those policy makers say they most want to help. The government’s intentions to reduce data protections will further reduce children’s effective routes to exercise their data rights and to seek redress.

The focus here is on safe children and families. It also depends on safe data. Trusted access to services relies in part on the rights of every children and families being respected, and transparent use of data, knowing who can access and who knows what about me.

We welcome further discussion with interested parties on counting children, to address these questions and concerns.

April 2022

Event presentation [download .pdf] 8MB

Presentation as handouts [download .pdf] 8MB

Download to print [this text article] .pdf 213 kB